In a swirl of sequins and shadowy spotlight, Yolanda Montes—the woman the world came to know as Tongolele—stepped onto the stage and redefined what it meant to be an “exotic.”

Born in Spokane, Washington, in 1932, Tongolele embodied a mélange of cultures: Spanish, Tahitian, Swedish, French, and English. That tapestry of ancestry shaped not just her look, but the sensuous, hypnotic style that set her apart on cabaret stages across Latin America. By 15, she was already performing professionally, and by her twenties, she had become the thunderclap that rumbled through the Golden Age of Mexican cinema.

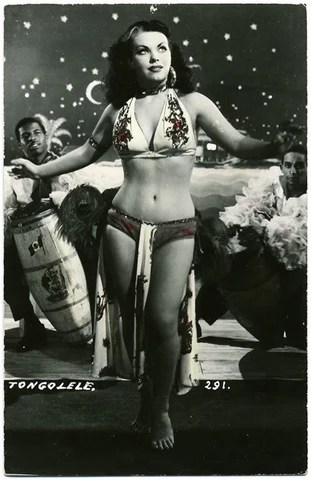

Tongolele’s performances were electric: she didn’t just dance—she possessed the stage. With her stark white streak of hair (which she wore shockingly young), her feline stare, and undulating hips, she conjured a persona that felt part goddess, part volcano. Her signature style was a fluid fusion of Tahitian and Afro-Caribbean movements that evoked mystery, rebellion, and a raw celebration of the body.

She starred in over 20 films, including ¡Han matado a Tongolele! (1948) and The Lovers (1951), becoming a fixture in Mexico’s nightlife and an immortal figure in the legacy of vedettes. But it wasn’t just her appearances on screen that left a mark—it was her power to command space in an era when women were expected to conform, to soften their edges, to play nice. Tongolele didn’t.

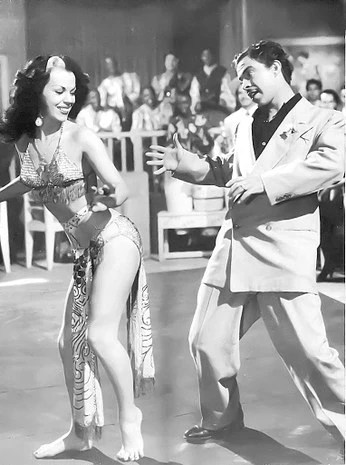

Tongelele in Burlesque

Tongolele’s burlesque work wasn’t just performance—it was provocation, pageantry, and power wrapped in sequins and rhythm.

While she’s often labeled a vedette—a term used in Latin America for glamorous cabaret stars—Tongolele’s artistry squarely intersected with the ethos of burlesque: sensuality as spectacle, identity as performance, and rebellion through embodiment. Her routines drew from Tahitian and Afro-Caribbean dance traditions, but she layered them with the slow tease and theatricality that defined classic burlesque. She didn’t strip in the traditional American sense, but she undressed expectations—challenging what femininity, race, and exoticism could look like on stage.

Her costumes were elaborate mosaics of feathers, beads, and flowing fabrics that shimmered with every movement. But it was her control—of her body, her gaze, her audience—that made her unforgettable. She could hold a room in silence with a single hip roll or a flick of her wrist. Her performances weren’t just about allure; they were about command.

Tongolele’s burlesque legacy also lies in how she blurred cultural lines. She fused Polynesian aesthetics with Mexican cabaret, creating a hybrid form that was both global and deeply personal. In doing so, she carved out space for performers who didn’t fit the mold—women of color, women with agency, women who danced not just to entertain but to own the stage.

She insisted on autonomy over her image and performances. She wasn’t a caricature to be scripted—she was the spectacle. And that insistence rippled beyond the footlights. Her longevity—dancing into her eighties and appearing in telenovelas into her nineties—wasn’t a fluke. It was the slow-burn payoff of an artist who built a persona larger than life, yet grounded in deliberate craft.

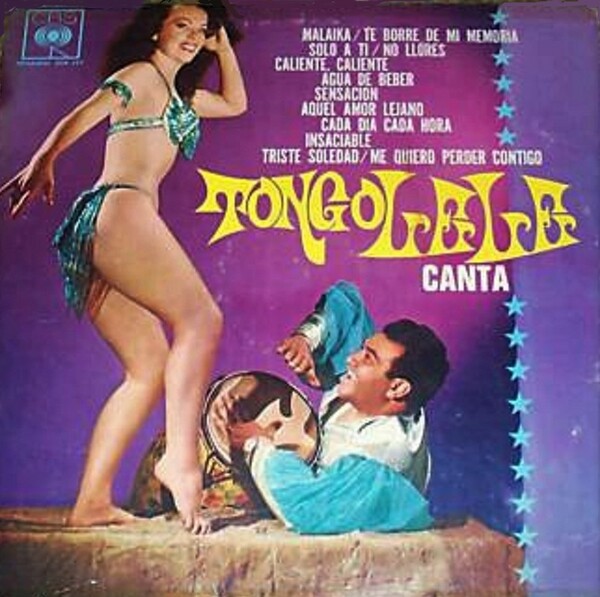

Tongelele in Tin Tan (1950)

Tongolele in Mambo de la muerte (1951)

Her Legacy

Tongolele’s legacy lives in today’s burlesque artists who find power in reclamation. In the soft and the sultry, in the wild and the unapologetic. She wasn’t just an exotic dancer—she was an orchestrator of fantasy, a master of embodied storytelling, and a defiant emblem of what it means to own the spotlight on your own terms.

Her last curtain call came in 2025, but the echo of her hips—undaunted, unbothered, unforgettable—still sways in every glittering feather fan and slow, deliberate pivot on the stage. Yolanda Montes died on February 16, 2025, at 93 years old.

Leave a comment