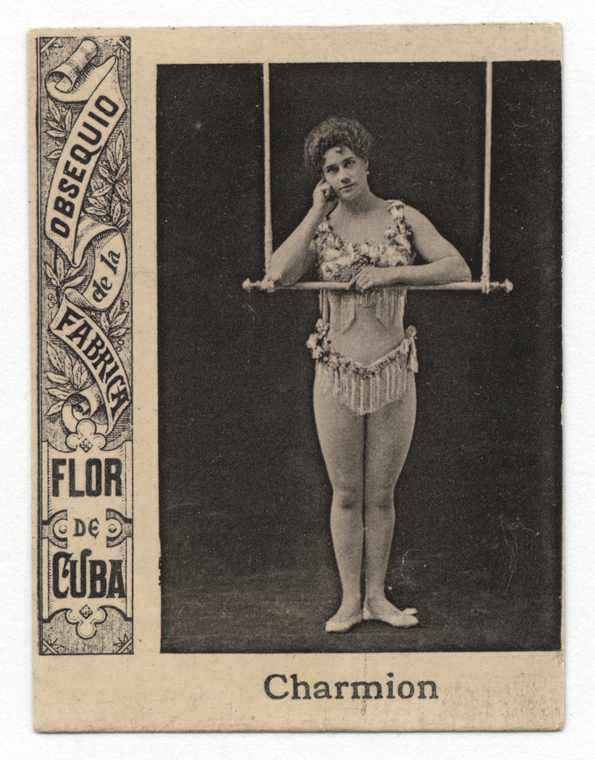

In the golden age of vaudeville, when corsets reigned and propriety was the law of the land, one woman dared to defy gravity—and society’s expectations. Her name was Charmion, and she wasn’t just a trapeze artist. She was a muscular marvel, a proto-feminist icon, and one of the first women ever filmed performing a striptease. And she did it all while hanging upside down.

From Sacramento to the Spotlight

Born Laverie Vallee Cooper in 1875 in Sacramento, California, Charmion began her career in gymnastics before leaping into vaudeville. She adopted the stage name “Charmion” and was often billed as French to add an exotic flair. But her act needed no embellishment—it was unlike anything audiences had seen.

Around the mid-1890s, she started gaining notice for her gymnastics on the rings, performing in Sacramento and San Francisco under the name Lavevi Charmion. After attempting to lead a local gymnastics troupe that didn’t find much success, she sought broader opportunities and joined the New York Vaudeville Company, eventually touring with them across the U.S. and Europe.

The Trapeze Disrobing Act

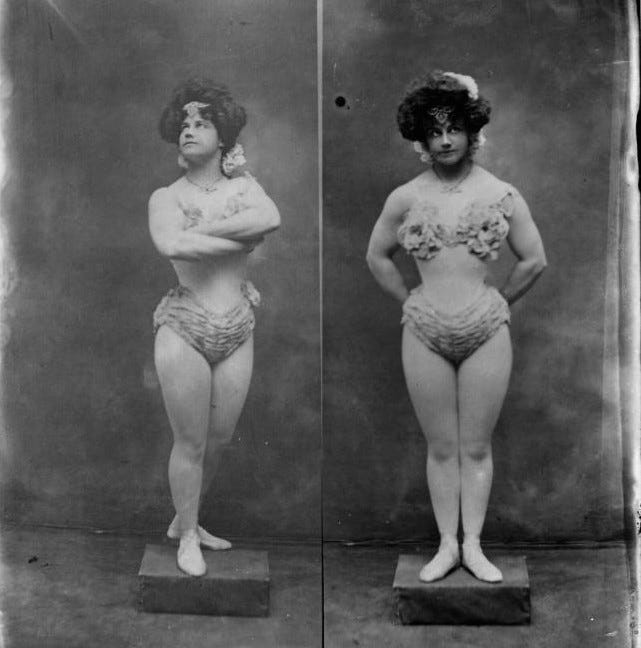

Charmion’s signature routine was as daring as it was theatrical. She would enter the stage in full Victorian dress—corset, bustle, hat, gloves—and climb onto a trapeze. As she swung high above the audience, she slowly removed each layer, revealing a leotard beneath. It wasn’t nudity that shocked the crowd—it was the audacity of a woman displaying strength, control, and sensuality in public.

During one of her performances, George Nathan Jean and his father were swept up in the act’s deliberately drawn-out tease. Charmion heightened the tension with every motion:

“By way of prolonging the terrible suspense, our temptress now maddeningly drew forth a small lace handkerchief from her bodice and cast it aside. She thereupon added insult to injury by slowly adjusting a hairpin in her coiffure. But wait! One by one now off came the stockings, revealing a pink silk garter underneath.”

By the time she reached the finale, she was clad only in a leotard—scandalous by the standards of the day, though not actually nude. The act stirred the audience into a frenzy, delighting some and shocking others. One Washington D.C. critic went so far as to condemn the performance as “revoltingly disgusting, coarse and disagreeable.”

In 1901, Thomas Edison filmed her act, titling it Trapeze Disrobing Act. The short film features two men watching her performance, clapping and catching her discarded garments—a clever cue to signal to real-life audiences that this was entertainment, not indecency.

Muscles and Morality

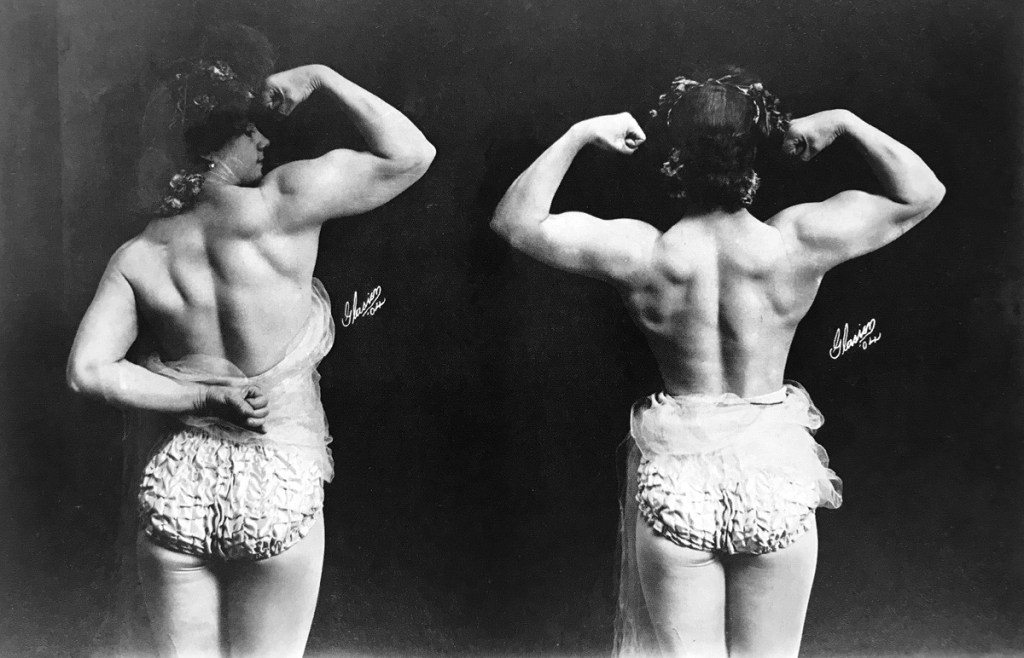

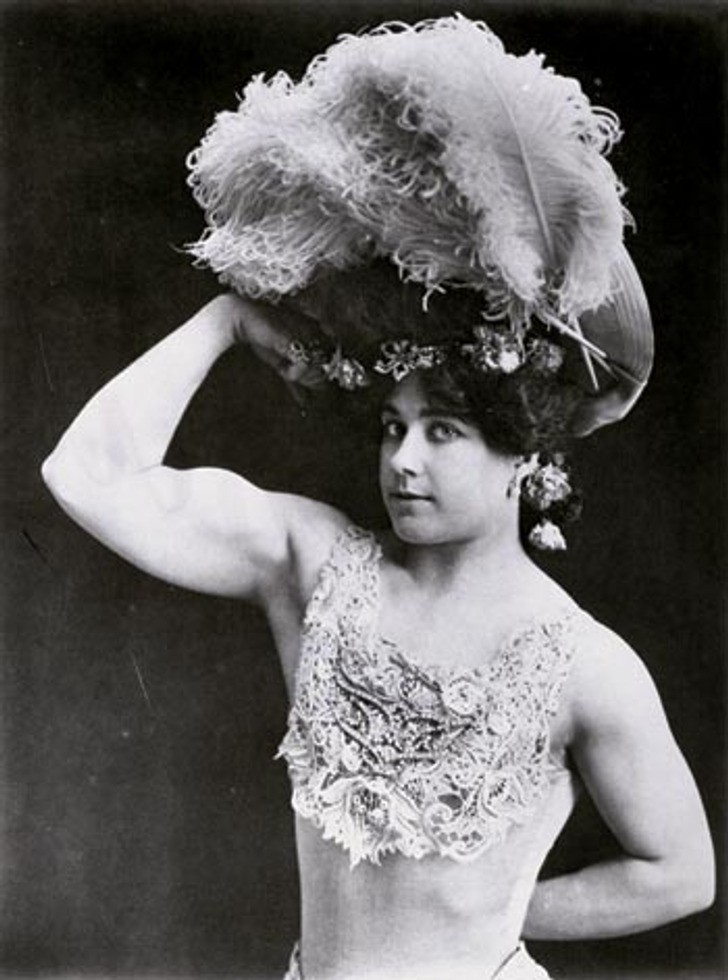

Charmion’s physique was muscular and unapologetic. At a time when women were expected to be delicate, she flexed her biceps and swung from the rafters. Critics called her “disgusting” and “coarse,” but she was also one of the highest-paid vaudeville performers of her time.

Her act aligned with the rise of physical culture, a movement that promoted health, fitness, and bodily reform. She wasn’t just performing—she was making a statement about women’s autonomy and strength.

Charmion performed in December 1897 at Koster and Bial’s theatre in New York City. Her act was described by the New York Dramatic Mirror:

“A few steps brought her to the rope by which she was hoisted on the trapeze. She then attempted one or two tricks, but seemed to find her clothes a bother, so she began to unhook her waist. When she began to take it off she exhibited all the shyness of a timid girl. Finally the waist came off.”

Touring, Teaching, and Trailblazing

Charmion toured across the U.S. and Europe, performing in major cities and even stepping in spontaneously when other acts failed. In one Paris show, she reportedly addressed the audience about fitness and beauty before launching into her aerial routine. She was frequently billed as “The Star of Vaudeville” or “The Queen of Vaudeville.”

She was part of a wave of women who used the stage to challenge Victorian ideals, paving the way for future performers—from burlesque queens to circus aerialists—who would blend athleticism with artistry. At the height of her fame, Charmion was making close to $500 a week on the Orpheum Vaudeville Circuit (same buying power as $16,401.28).

Harry Delaney, who served as Charmion’s husband, manager, and trainer, passed away in 1905. Several years later, in 1912, she married again—this time to a wrestler named William Vallee. Eventually, she returned to her home state of California, where she spent her later years and passed away in 1949 in Santa Ana, Orange County.

Charmion & The Evolution of Burlesque

Though she was never billed as a burlesque performer, Charmion’s aerial striptease carved out new territory that would echo through the art form for decades to come. Her act blurred genre boundaries—melding the athletic spectacle of vaudeville, the sensuality of striptease, and the assertiveness of physical culture. In doing so, she helped shape the DNA of what we now recognize as burlesque. Her famous routine—a slow disrobing while suspended on a trapeze—offered something more than titillation. She told a story through movement and removal, building tension one garment at a time. Audiences didn’t just watch her—they anticipated her. This teasing structure, centered on pacing, buildup, and audience engagement, became a cornerstone of burlesque performance.

By beginning fully costumed and ending in a leotard, Charmion wasn’t just undressing—she was peeling away societal constraints. In an era when women’s bodies were subject to strict norms, her muscular physique and bold movements offered a counter-narrative. Her strength was the spectacle, not something to be hidden. This physical assertion of presence and power paved the way for performers who would later use burlesque as a vehicle for self-expression, satire, and bodily autonomy.

The filmed version of her act—produced by Thomas Edison—adds an extra layer of complexity. In it, two male spectators observe her performance, clapping and catching garments as she drops them. Their inclusion serves as a built-in audience surrogate, offering “acceptable” cues for how viewers were expected to respond. This self-aware interplay between performer and gaze would become a hallmark of classic burlesque, where spectatorship is as much a part of the act as the performer herself.

Charmion’s legacy lives on in the lineage of performers who followed. Her mix of glamour, muscle, and theatricality can be seen in mid-century legends like Lili St. Cyr and in the politically charged acts of modern neo-burlesque artists. She may not have set out to change the world from her trapeze, but with each calculated swing and discarded glove, she redefined the boundaries of femininity, performance, and desire.

Legacy in Motion

Charmion’s story is more than a novelty act—it’s a lens into a moment when women were beginning to claim space, both onstage and in society. She swung into the spotlight not just to entertain, but to redefine what strength could look like in a woman’s body. Whether you see her as a vaudeville rebel, a feminist foremother, or a dazzling footnote in early cinema, one thing’s certain: Charmion didn’t just hang from the rafters—she raised the bar!

Sources

Websites

- https://flashbak.com/charmion-the-victorian-era-strongwoman-who-stripped-462165/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charmion

- https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/lot-charmion-poses-vaudeville-orpheum-1811545178

- https://www.reddit.com/r/WitchesVsPatriarchy/comments/11kz0jh/strongwoman_and_trapeze_artist_laverie_vallee/

Leave a comment