In the twilight of the 19th century, as Japan opened its doors to the world, one woman stepped through them and onto the global stage with unmatched grace and audacity. Sada Yacco, born Sadayakko Kawakami in 1871, was not only Japan’s first international performing arts star—she was a cultural ambassador, a theatrical innovator, and a muse to the West.

Sadayakko was born on July 18, 1871 and was the youngest of twelve children. Her family was once wealthy but heavy taxes and rising inflation caused the family to lose their wealth. Her parents opened a pawn shop to make ends meet. At age 4 she was sent to work as a maid in the Hamada geisha house.

In the winter of 1883, at just 12 years old, her father died, prompting the head proprietress Kamekichi to adopt Sada asa her own heir. So she entered the world of geisha as an o-shaku, an apprentice, and was given her first stage name: Ko-yakko, meaning “Little Yakko.”

Geisha

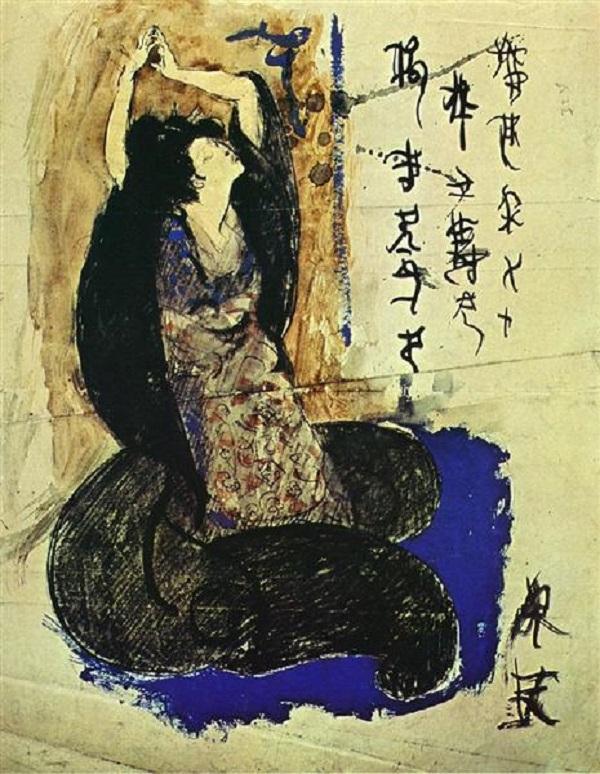

Geishas, often misunderstood in Western portrayals, are traditional Japanese female entertainers trained in the refined arts of music, dance, conversation, and hospitality. Emerging during the Edo period (1603–1868), geishas cultivated a distinct cultural role: they were not courtesans, but rather artists and companions whose allure lay in their wit, elegance, and mastery of performance. Their iconic appearance—white face makeup, elaborate kimono, and stylized hair—was not merely aesthetic but symbolic, signaling their status and artistic dedication. Geishas performed at ochaya (teahouses), private gatherings, and public events, offering a curated experience of Japanese cultural sophistication.

Defying social norms of the period, her adoptive mom wanted her career to blossom. She studied literacy under a Shinto priest—an extraordinary opportunity when formal education for women was still rare. The first school for noblewomen didn’t open until 1870.

Privately and secretly, she also immersed herself in judo, horseback riding, and billiards, developing skills far outside the traditional expectations of her role. She even took part in professional races – marking how “unconventional and progressive she was.” (Downer, Leslie) She met a man named Momosuke Fukuzawa during a horseback ride, sparking a friendship.

Mizuage

Mizuage (水揚げ, meaning “hoisting from water”) was a traditional rite marking the transition to adulthood for apprentice courtesans. For maiko, the ceremony was part of a broader graduation into geisha, involving changes in hairstyle and formal visits to mentors. Before prostitution was outlawed in Japan, mizuage often involved wealthy patrons bidding large sums for a maiko’s virginity, with all proceeds going to the okiya, or geisha house.

In 1886, at age 15, her mizuage is bought by the first Prime Minister of Japan, Ito Hirobumi. Her high-profile relationship with the Prime Minister significantly elevated her status within teahouse circles. Their connection lasted for three years.

Within the refined confines of geisha entertainment, Yacco uncovered a deep affinity for dramatic performance. While geisha traditionally entertained with music and dance inspired by kabuki, these acts were reserved for intimate, select audiences. Yacco found herself captivated by the powerful male roles—brimming with bold stances and choreographed combat—rather than the gentle, flirtatious roles typically assigned to women.

After three years as Prime Minister Hirobumi’s mistress, Yacco was released from the arrangement and faced an uncertain future. Conventional wisdom might have pointed her toward marriage for financial stability, yet Yacco defied expectations. Surrounded by admirers and patrons, she showed little inclination to settle into domestic life—until she crossed paths with the charismatic performer and political satirist Otojirō Kawakami.

Their meeting marked a turning point, both personally and professionally, setting the stage for a partnership that would reshape Japanese theater and carry Yacco onto the global stage.

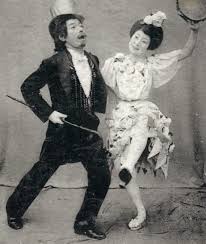

Marrying Otojirō Kawakami | Actor & Political Satirist

Otojirō Kawakami burst onto the scene with a satirical song that felt like proto-beatboxing—an electrifying, rhythmic takedown of Japan’s nouveau riche that blended biting social critique with streetwise flair. The song was a hit! He called himself “The Liberty Kid” and was known for his cocky self confidence and self-deprecating comedic style.

Riding the wave of that success, he pioneered a bold theatrical movement later known as Shinpa (“new school”), which broke from Kabuki’s rigid traditions to embrace realism, modern themes, and Western staging techniques. His brash charisma and relentless ambition made him a magnet for controversy—and for Sadayakko.

The tabloids scoffed at the match: a refined, high-ranking geisha entangled with a theatrical provocateur who seemed more hustler than visionary. But was unmoved. She cast off her patrons, dismissed societal expectations, and married Kawakami in 1893 (or 1894), formally resigning her geisha status to step into a new role—partner, performer, and cultural trailblazer.

Kabuki Theater

Kabuki is a classical Japanese theater form known for its stylized drama, elaborate costumes, and dynamic stagecraft. Originating in the early 17th century, it blends music, dance, and exaggerated performance to tell stories ranging from historical epics to domestic tragedies.

Ironically, kabuki itself was founded by a woman—Izumo no Okuni, a temple dancer who began performing comic sketches and dances in 1603. In its early days, kabuki was a bawdy, street-level art form performed exclusively by women, many of whom came from working-class or sex work backgrounds. But after Okuni’s death, women were banned from the kabuki stage, and public performance was off-limits until 1872. Even then, it took another two decades before women were allowed to share the stage with male actors. To this day, most kabuki troupes remain all-male.

Modern Japanese Theater

Together, they founded a Western-style theater in Tokyo and pioneered Shinpa, a modern theatrical movement blending Kabuki traditions with Western realism.

Sōshi shibai

Sōshi shibai was an early form of Shinpa theater that fused political activism with melodrama. Inspired by Meiji-era radicals (sōshi), it featured impassioned speeches and topical plots, often staged in informal venues. This gritty, populist style paved the way for Shinpa’s later refinement and broader appeal.

Shinpa

Shinpa (literally “new school”) was a modernizing force in Japanese theater that emerged in the late 19th century, challenging the stylized conventions of classical forms like Kabuki. Rooted in realism and contemporary storytelling, Shinpa embraced Western dramaturgy, melodrama, and topical themes—often focusing on social issues, romantic entanglements, and the emotional lives of ordinary people. It was a genre of transition, blending traditional aesthetics with modern sensibilities, and it resonated with audiences navigating Japan’s rapid modernization during the Meiji era.

Sada Yacco played a pivotal role in helping Kawakami secure funding for a Western-style theater in Tokyo—a bold venture that earned critical acclaim but left them financially overextended. Kawakami’s brief foray into politics only deepened their debt, ultimately forcing them to sell the theater. Disheartened and eager to escape their mounting troubles, the couple set off on an unconventional journey aboard a ramshackle boat.

What began as a retreat turned into a wandering performance tour through fishing villages from Tokyo to Kobe, with Kawakami captivating locals through spontaneous storytelling. The press gleefully chronicled their escapade, dubbing it a “madcap voyage.” By the time they reached Kobe in January 1899, a jubilant crowd awaited their arrival.

Among the onlookers was Yumindo Kushibiki, an entrepreneur who had established a Japanese tea garden in Atlantic City. He offered to sponsor a U.S. tour stretching from San Francisco to his East Coast venue. Kawakami eagerly accepted, and the couple quickly organized a troupe to perform a selection of traditional kabuki plays—works chosen for their timeless appeal and cross-cultural resonance.

The troupe was composed of 18 people: 9 male actors, two child actors, a costumer, a props manager, a hairdresser, a singer, a shamisen player, a bag carrier, and Yakko. Just three months later, they set sail from Kobe, bound for San Francisco and a new chapter on the international stage.

Performing in the United States

Sada Yacco stood out as the sole woman in an otherwise all-male troupe, carving a singular space for herself during their year-long tour across America. As the journey unfolded, her performance style matured—favoring subtle, expressive movements and nuanced facial expressions that mesmerized audiences. In contrast to Kawakami’s flair for dynamic, realistic fight choreography, Yacco’s quiet intensity brought emotional depth to the stage. Their breakout production, The Geisha and the Knight, became a crowd favorite, showcasing the duo’s complementary strengths with fight scenes and an emotional and dramatic death scene of Yacco.

Sada Yacco later recalled that she had planned to join the tour simply as Kawakami’s wife, offering support behind the scenes. But upon arrival, she was stunned to find herself promoted as the company’s leading star—her image plastered across city streets, and her name headlining press coverage. The San Francisco Chronicle announced her arrival with fanfare: “Madame Yacco, the Leading Geisha of Japan Coming Here!”

In San Francisco, Yacco fused her childhood name, Sada, with her geisha name, Yacco, and stepped into the spotlight as Sada Yacco. Her debut captivated audiences, even as critics struggled to interpret the unfamiliar theatrical style. The San Francisco Examiner was effusive, calling her “the most celebrated geisha in Japan,” and noting that she could enchant an entire theater—even one filled with Westerners who didn’t understand a word she spoke.

A Nightmare or a Dream?

The U.S. tour quickly unraveled after they arrived in San Francisco. Their sponsor, Yumindo Kushibiki, suffered a financial setback and abruptly withdrew support, leaving the troupe stranded. With nowhere to turn, they leaned on the generosity of Japanese-American communities to survive. They made their way through Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland, but hit rock bottom in Chicago, where some actors resorted to camping along the river.

Salvation came unexpectedly at the Lyric Theatre, where the manager’s daughter—an avid collector of Japanese art—convinced her father to grant them a single Saturday matinee slot. Luckily, their arrival coincided with America’s fervent fascination with Japanese culture, sparked decades earlier by Japan’s opening to the West. The matinee drew a full house and proved a triumph, even though the performers were so malnourished they struggled through the choreography. Sada Yacco herself nearly collapsed mid-spin, but the audience never noticed—they were utterly spellbound.

Their two-month engagement in Boston was a triumph, drawing the city’s fashionable elite—including renowned actors Sir Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, who were performing nearby. Kawakami and Sada Yacco attended their staging of The Merchant of Venice, and Kawakami, inspired, quickly penned a Japanese adaptation with Yacco in the role of Portia. It was the first of several Shakespearean works he would reinterpret. Throughout their tour, the couple immersed themselves in Western theatrical traditions, expanding their artistic vocabulary.

They performed from the West to East coasts, including Washington, Oregon, Michigan, and Ohio. They later performed in New York City on Broadway and Washington, D.C., appearing before President William McKinley.

Conquering Europe

In 1900, the troupe began touring England, then France, Germany, and Berlin.

A stop in London included a performance for the Prince of Wales, before they arrived in Paris under the patronage of Loïe Fuller, famed for her Serpentine dances.

As a savvy impresario, Fuller imposed her own vision of Japanese theater on Kawakami’s troupe, demanding that each piece end with a dramatized hara-kiri—ritual suicide by disembowelment. She advertised it boldly: “Hara-Kiri scene today!” Parisians flocked to the spectacle, cheering the grisly finales. Even Sada Yacco was compelled to incorporate a female hara-kiri into her dance routine.

Despite their mission to modernize Japanese theater, Yacco and Kawakami found themselves navigating Western audiences’ appetite for “exotic” spectacle. They were often boxed into stereotypes—expected to deliver a fantasy of Japan filled with delicate, doll-like women and dramatic rituals like hara-kiri. Yet even within these constraints, they managed to challenge and complicate those perceptions.

As the New York Times observed, Sada Yacco “shows plainly that a Japanese woman can love deeply, hate savagely, and then die quietly,” revealing emotional depth and complexity that defied the caricatures imposed on her.

Sadda Yacco’s fame extended across Europe—while in Russia, she dined with Tsar Nicholas II and was astonished to see men lay their coats on the ground just to preserve the impression of her footsteps. Haper’s Bazaar added a moniker to Yacco, naming her “Japan’s Greatest Emotional Actress” in 1900.

In June 1901, Loïe Fuller arranged a second European tour for the troupe, briefly joined by dancer Isadora Duncan. They performed in Glasgow, Paris, Berlin, Brussels, Vienna, Budapest, Rome, and so many more.

Creative tensions between Kawakami and Loïe Fuller eventually caused their partnership to dissolve. On July 4, 1902, the Japanese troupe made their return to Tokyo. Back home, Sada Yacco resumed performing—taking on roles in Shakespearean adaptations staged by Kawakami, continuing their artistic collaboration on familiar ground.

Inspiring Artists, Composers & Authors

Sada Yacco’s performances left a lasting impression on composer Giacomo Puccini during her 1901 tour in Milan, where he was developing the opera Madame Butterfly. Captivated by her artistry, Puccini reportedly incorporated a melody she played into the opera and even eliminated an entire act, inspired by the concise power of Kawakami’s adaptations. Her presence helped shape Western interpretations of Japanese femininity, blending theatrical elegance with emotional depth that resonated in Puccini’s tragic heroine.

Sada Yacco dazzled audiences at the Paris Exposition, earning praise from literary giant André Gide, who admitted to attending her performance six times.

He wrote, “In her rhythmic, measured passion, Sada Yacco gives us the sacred emotion of the great dramas of antiquity, which we seek and no longer find on our own stage.”

Her artistry left a profound mark on pioneers of modern dance—Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan—who credited her with reshaping their creative vision.

St. Denis reflected, “Her performances haunted me for years, and filled my soul with such a longing for the subtle and elusive in art that it became my chief ambition as an artist.”

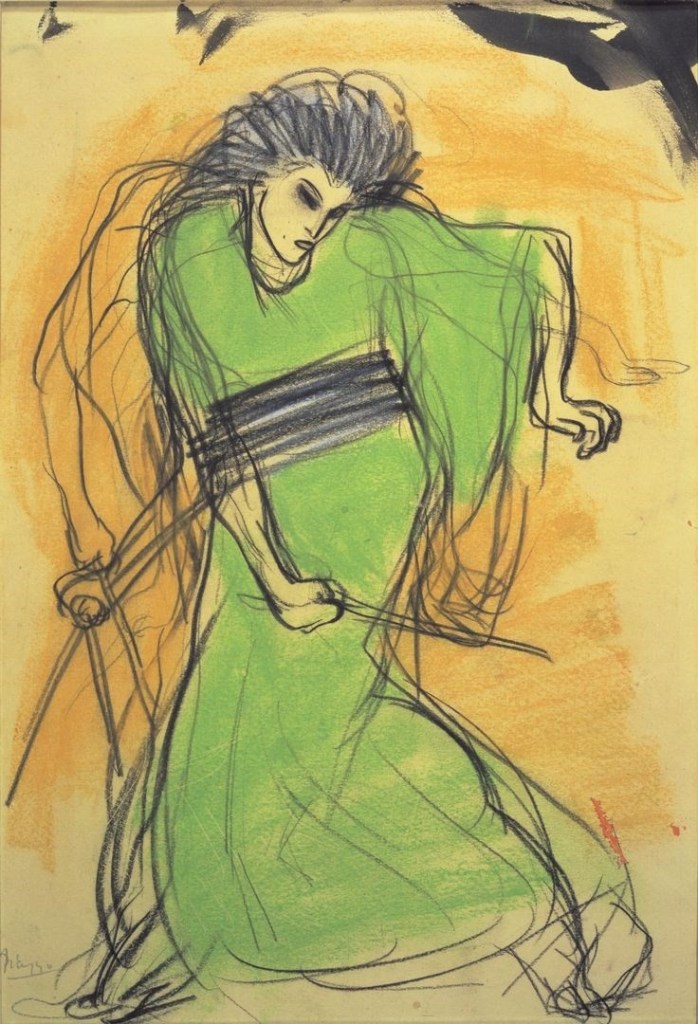

Yacco’s magnetism extended beyond the stage: she was sketched by a young Picasso, admired by Rodin, and graced the covers of countless magazines, becoming a global icon of theatrical elegance and innovation.

Culture & Fashion Icon

While in France, Yacco turned her name into a luxury brand! Her name became synonymous with elegance and Japanese-inspired fashion. The boutique Au Mikado capitalized on her rising fame, securing rights to use “Yacco” as a brand. Their offerings included Yacco-branded perfumes, skin creams, confections, and most notably—the “Kimono Sada Yacco.”

Brand Au Mikado; Label KIMONO SADA YACCO Marque Déposée Au Mikado PARIS 日本物品

Before its release, Westernized kimono styles were prohibitively expensive and reserved for the elite. But the “Kimono Sada Yacco,” priced accessibly at 12 to 18 francs, brought the look into reach for everyday women, democratizing the aesthetic and turning Yacco’s image into a fashion movement.

Returning to Japan

Following the success of their European tour, Sada Yacco and Kawakami returned to Japan and deepened their theatrical fusion of Eastern and Western traditions. Kawakami reimagined works like Othello, Hamlet, The Three Sisters, La Dame aux Camélias, and Ibsen’s The Enemy of the People, all featuring Yacco in leading roles.

Decades ahead of England’s experiments with modern-dress Shakespeare, Kawakami shocked traditionalists by staging Hamlet in a school uniform, entering on a bicycle. His bold reinterpretations of classic texts—once radical—are now commonplace in contemporary theater.

Though later criticized for diluting both kabuki and Western drama, Kawakami’s work marked the first meaningful theatrical exchange between Japan and the West. Together, he and Sada Yacco forged a new artistic language that challenged conventions on both sides.

In 1907, they made one final journey to Europe. Yacco studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, and the pair staged Japanese-inflected versions of Western plays. Upon returning to Japan, they established the Imperial Theater in Osaka.

Legacy and Later Life

In 1908, Yacco founded the Imperial Training Institute, Japan’s first school for professional actresses. Out of 100 applicants, Yacco selected 15 students, and the school opened on September 15, 1908.

“I would like to train accomplished actresses, who might come to be called the Sarah Bernhardts of Japan.”

Following the death of Otojiro Kawakami, Sada reconnected with her longtime acquaintance Momosuke Fukuzawa, a married businessman she had known since childhood. By the spring of 1912, their bond had deepened into an open companionship—one that defied social conventions. While extramarital relationships weren’t unheard of in Japan, they were typically kept discreet.

In contrast, Yacco and Momosuke lived and traveled openly together, their public flirtations stirring scandal and conversation. Undeterred by critics, they remained steadfast in their support for one another—Sada now selecting her own stage roles, while Momosuke pursued a growing portfolio of business ventures.

Sada retired from performance in September 1917, taking her final bow as the lead in the opera Aida. With her departure from the stage, she relinquished both her professional and geisha names, signaling a complete transformation. However, she did establish a children’s theater in Tokyo in 1924, furthering her commitment to the arts.

Years later, in 1933, with Momosuke’s health in decline, they made the difficult decision to part ways. He returned to live with his wife in Shibuya, and the couple—having spent over two decades together—marked their separation with a solemn farewell ceremony. She eventually returned to Tokyo in 1938.

Sada Yacco lived through the turmoil of World War II, but not long after Japan’s surrender, she was diagnosed with liver cancer that had metastasized to her throat and tongue. She passed away on December 7, 1946, at the age of 75, leaving behind a legacy defined by artistry, audacity, and personal reinvention.

The Burlesque Connection

Sada Yacco’s relationship to burlesque is more indirect than formative—she wasn’t shaped by burlesque traditions herself, but her theatrical presence and global tours certainly influenced how Western audiences perceived Japanese femininity and performance, including within burlesque-adjacent spaces.

A key hallmark of burlesque is its choreography: every shrug, wink, and step carries character. Yacco’s technique mirrored this, especially through shosagoto, a form of Kabuki dance-drama that uses expressive movement to tell stories. Her theatrical style became an indirect blueprint for performers who wanted more meaning in their performance.

Her appearances at Loie Fuller’s pavilion during the 1900 Paris Exposition, for instance, placed her alongside dancers and performers who were experimenting with light, costume, and sensuality. Though Yacco herself maintained a more tragic and refined stage persona, her aesthetic—ornate kimono, expressive gestures, and theatrical death scenes—left a lasting impression on Western artists, including burlesque and cabaret performers who borrowed from Japonisme and exoticized Eastern motifs.

While Yacco wasn’t influenced by burlesque in the traditional sense, she helped shape its visual vocabulary from the outside. Her legacy is more about inspiring others—introducing Japanese theatricality to Western stages and expanding the palette of what sensual, dramatic, and feminine performance could look like. In that way, she was a muse to burlesque, not a product of it.

Sources

- https://www.messynessychic.com/2021/09/28/the-geisha-who-brought-kabuki-to-the-west/

- https://pen-online.com/culture/the-story-of-sada-yacco-the-japanese-geisha-who-bewitched-europe/

- https://tfsimon.com/sada-yacco-interview-1906.htm

- https://www.dazeddigital.com/beauty/article/42747/1/sada-yacco-japan-prominent-original-beauty-influencer

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sada_Yacco

- https://chumediahub.wordpress.com/2021/02/12/influential-japanese-women-sada-yacco/

- https://www.artic.edu/artworks/129544/sada-yacco

- https://www.munich-dance-histories.de/en/people/sada-yacco/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mizuage

Photographs

Books

- Downer, Leslie (2003). Madame Sadayakko: The Geisha Who Bewitched the West. Gotham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59240-050-8.

- Garelick, Rhonda K. Electric Salome: Loie Fuller’s Performance of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007., ISBN 9780691017082.

Leave a comment