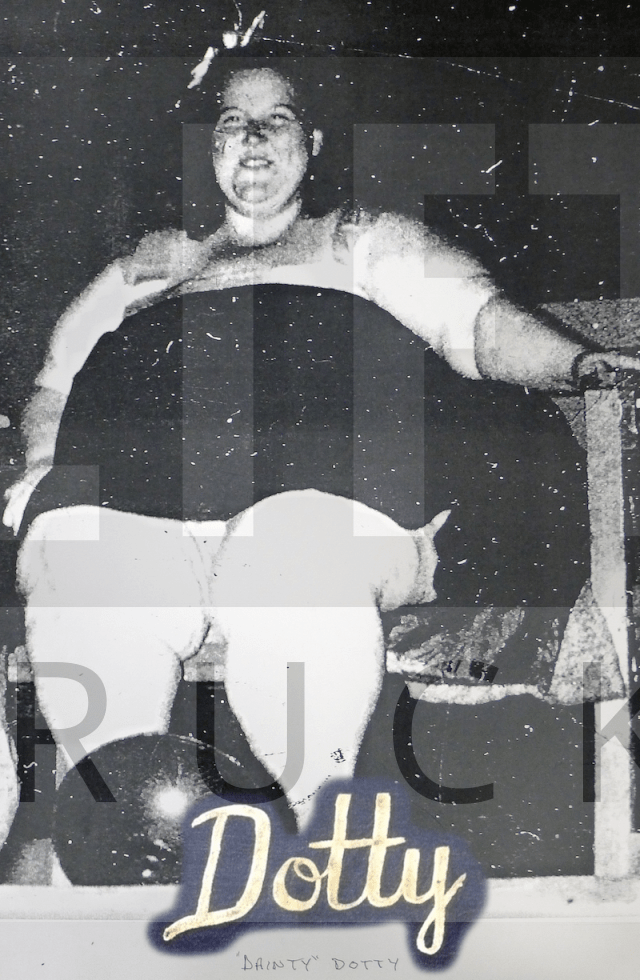

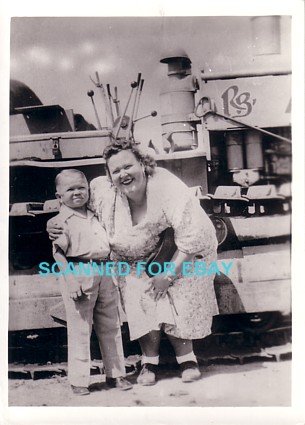

In the dust and dazzle of America’s mid-century circus culture, Florence Jensen — better known as “Dainty Dotty” — stood out not just for her size, but for her ink. Billed as a “fat lady” in the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus during the 1930s and ’40s, Dotty was more than a sideshow attraction. She was a tattoo artist, a businesswoman, and performer!

The Circus as Cultural Theater

By the time Dotty joined the Ringling Bros. in the 1930s, the circus was a sprawling cultural institution. Founded in 1871 and merged with Barnum & Bailey in 1919, Ringling was known for its “Congress of Freaks” — a lineup of performers whose bodies defied social norms. Fat ladies, bearded women, sword swallowers, and tattooed men were presented as curiosities, but they also carved out spaces of agency and artistry.

Dotty’s billing as “Dainty Dotty” was a wink at the audience — a deliberate contradiction that invited spectators to reconsider their assumptions about femininity and spectacle. Weighing over 500 pounds, she performed alongside Major Mite, a man under three feet tall, in a classic pairing of extremes. But unlike many performers who remained passive exhibits, Dotty took control of her narrative.

Dainty Dotty and Burlesque

“Dainty Dotty” Jensen also flirted with the aesthetics of burlesque — a genre that celebrated theatrical sensuality, satire, and bodily spectacle. In one surviving promotional photograph, Dotty poses nude behind two ornate lace fans, her expression confident and playful.

The image, credited to Theatrical Chicago, echoes classic burlesque iconography: concealment and reveal, exaggeration and elegance. For a fat woman in mid-century America, such a pose was radical. It challenged dominant beauty standards and reclaimed erotic agency in a culture that often rendered large bodies invisible or comedic.

Dotty’s use of fans — a staple of burlesque tease — suggests she understood the language of glamour and subversion, blending circus bravado with the flirtatious poise of the burlesque stage. Lace fans were not super common, like ostrich feather fans, and hardly conceal anything behind the lace.

Tattooing in a Time of Taboo

Tattoos in the 1920s: Exoticism & Performance

In the 1920s, tattoos were still largely associated with sailors, circus performers, and “exotic” spectacle. Anchors, swallows, and patriotic symbols were common among servicemen, while tattooed ladies appeared in sideshows as living canvases. Tattooing was also used cosmetically — women sometimes tattooed permanent makeup like lip liner or eyebrows, especially when cosmetics were expensive or inaccessible.

Despite these uses, tattoos were still stigmatized. The American aristocracy and middle classes often viewed them as vulgar or low-class. Ward McAllister, a prominent socialite, famously called tattooing “barbarous” and “illiterate.” So while tattoos were present in performance and fringe communities, they weren’t widely accepted in polite society.

Tattoos in the 1940s: War & Patriotism

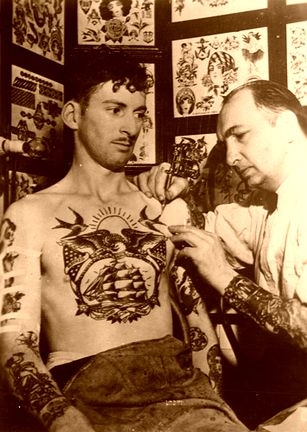

World War II shifted tattoo culture dramatically. Sailors and soldiers often got tattoos as symbols of loyalty, remembrance, or bravado — think “Mom,” “Victory,” or unit insignias. Tattoo shops flourished near naval bases, and artists like Sailor Jerry helped popularize bold, American-style flash.

Yet even in this patriotic context, tattoos remained gendered and classed. Men could wear tattoos as marks of service or toughness. Women with tattoos, however, were often seen as deviant — associated with sex work, criminality, or sideshow performance. Fat women, in particular, were rarely imagined as tattoo artists. Their bodies were already coded as excessive or comedic, and adding tattoos only amplified their perceived transgression.

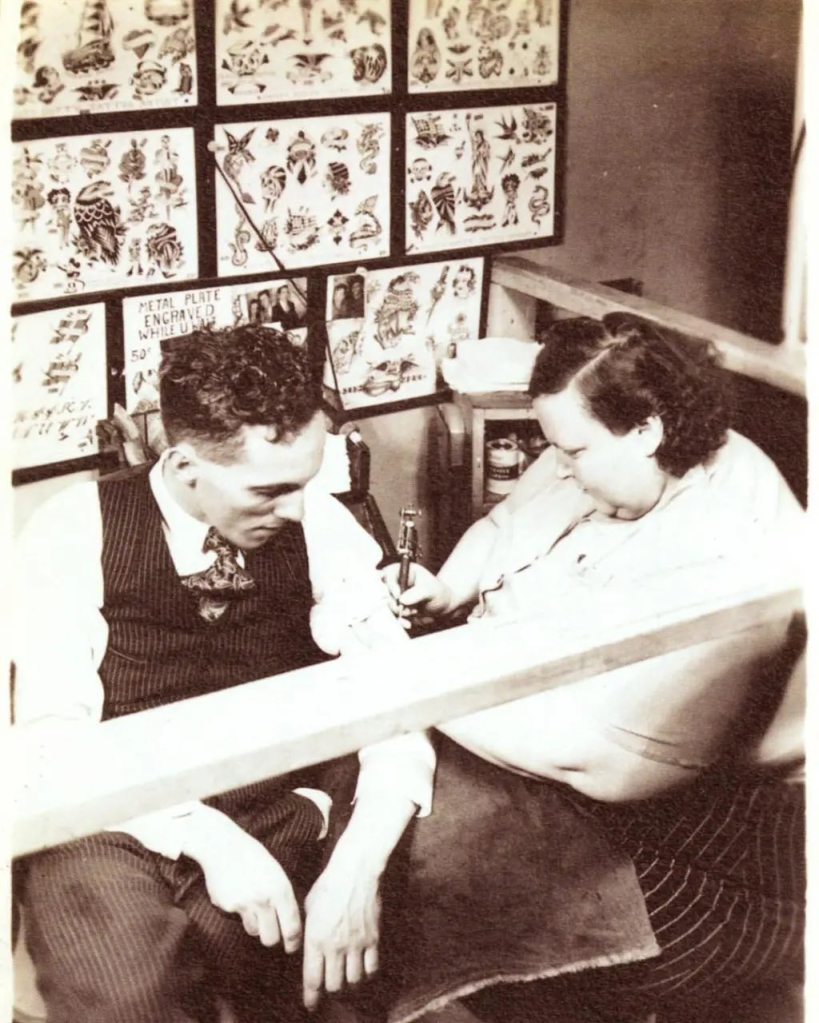

That’s what makes Dotty so extraordinary. She didn’t just wear tattoos — she made them, tattooing herself and others. In a time when tattooing was seen as masculine, marginal, and often criminal, Dotty carved out space as a woman artist and performer. Her presence disrupted every norm.

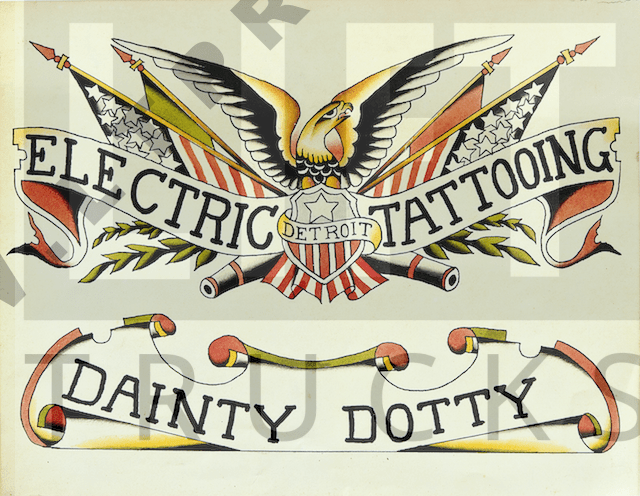

Electric Tattooing in Detroit, MI

In the late 1930s, Florence “Dainty Dotty” Jensen began tattooing in Detroit, a city then booming with industrial labor, wartime manufacturing, and a growing tattoo scene. Detroit was home to J.G. Barber, one of the earliest American tattoo artists to operate a formal studio, and it was a hub for machinists and craftspeople.

It’s believed that Dotty’s first exposure to electric tattooing came during this period. Detroit offered her not just a new skill set, but a new identity: no longer just the “fat lady” on display, she became a practitioner of a craft that was still seen as masculine, mechanical, and marginal. For a fat woman to enter this space — and succeed — was radical.

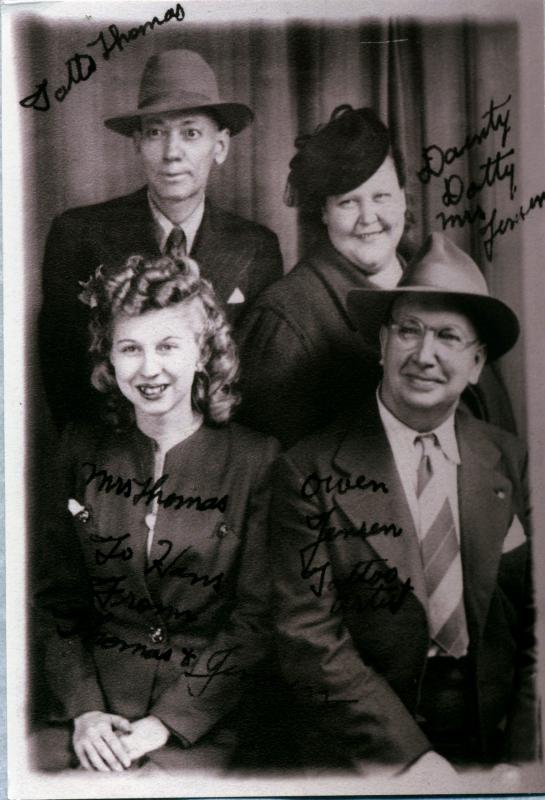

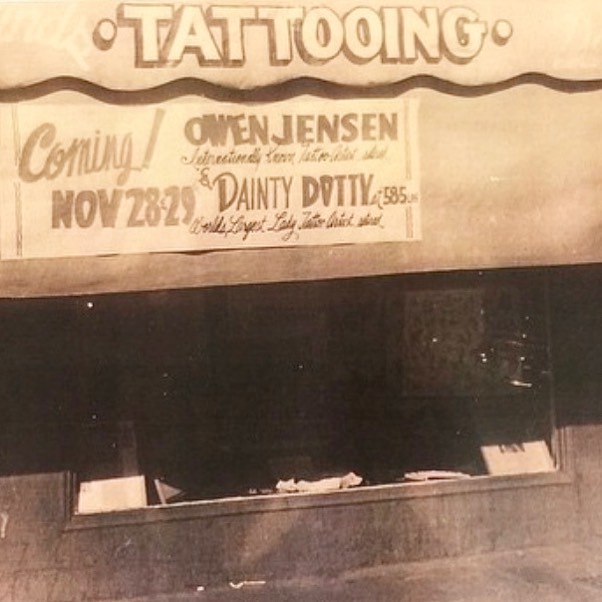

Ink & Intimacy: Dotty and Owen Jensen

Florence met Owen Jensen in the late 1930s, likely while working in Detroit or through the tattooing circuit in Southern California. Owen Jensen, born in 1891, was already a well-established tattoo artist and machinist, known for building tattoo machines and supplying equipment to artists across the country. He had been working on The Pike in Long Beach since 1929 — a bustling boardwalk of amusements, arcades, and tattoo shops that served sailors, tourists, and performers alike.

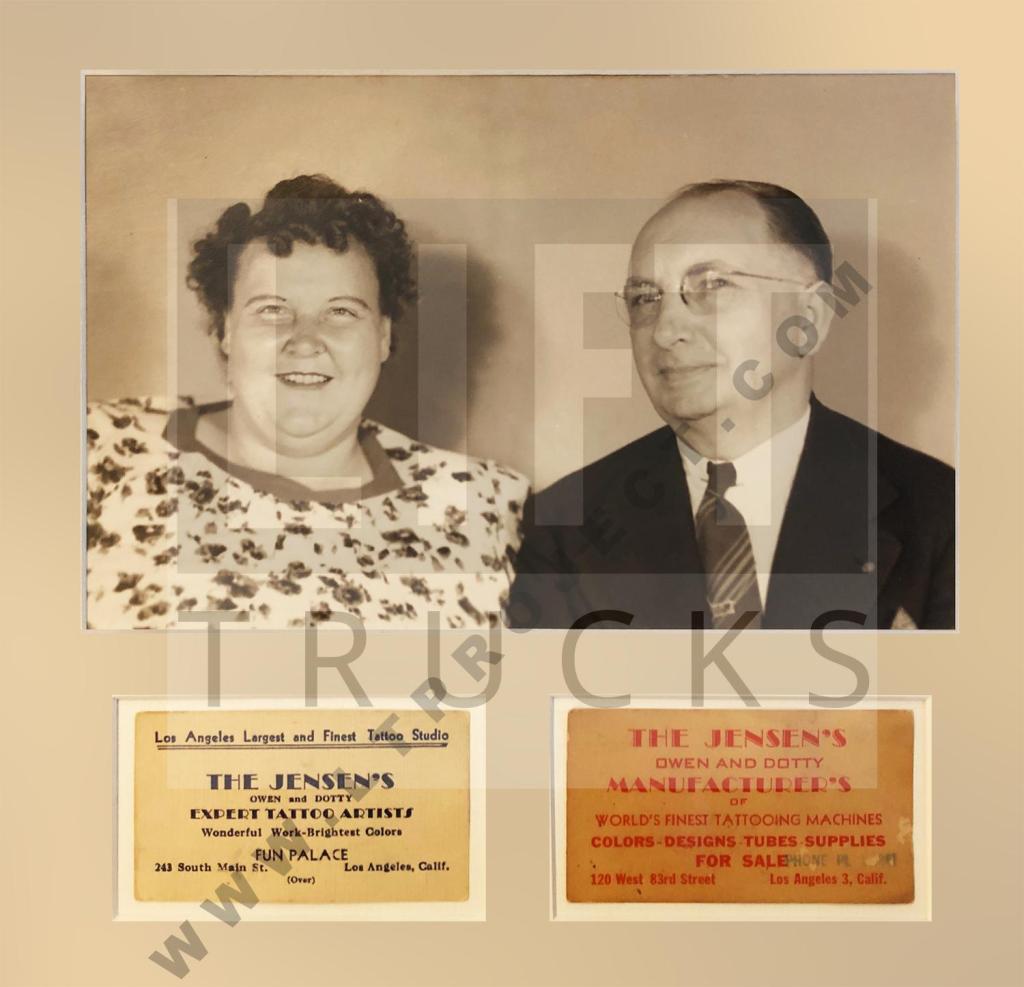

Their relationship blossomed into marriage, though the exact date remains elusive in public records. What is clear is that Dotty and Owen became creative and commercial partners.

Together, they ran a tattoo supply business and operated a studio in Los Angeles, with Dotty reportedly tattooing clients herself — a rare role for a woman in the 1940s, and even rarer for a fat woman in a culture that often denied her agency. She also reportedly tattooed herself, though no photos of those tattoos exist.

Owen’s technical expertise and Dotty’s performative flair made them a formidable duo. While Owen focused on machine design and supply logistics, Dotty embodied the art — her tattooed body a living advertisement, her presence a challenge to gendered expectations in both circus and tattoo culture. Their marriage was more than domestic; it was a collaboration that helped shape the West Coast tattoo scene during a pivotal era.

Tattoo Evidence

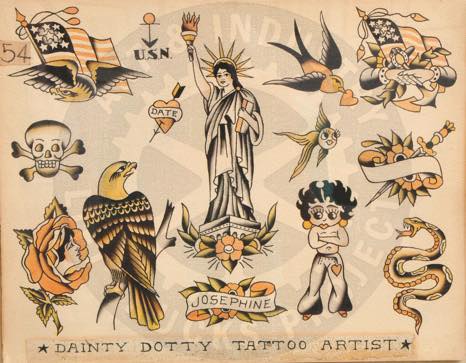

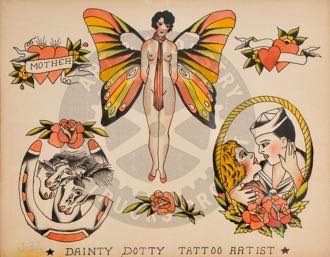

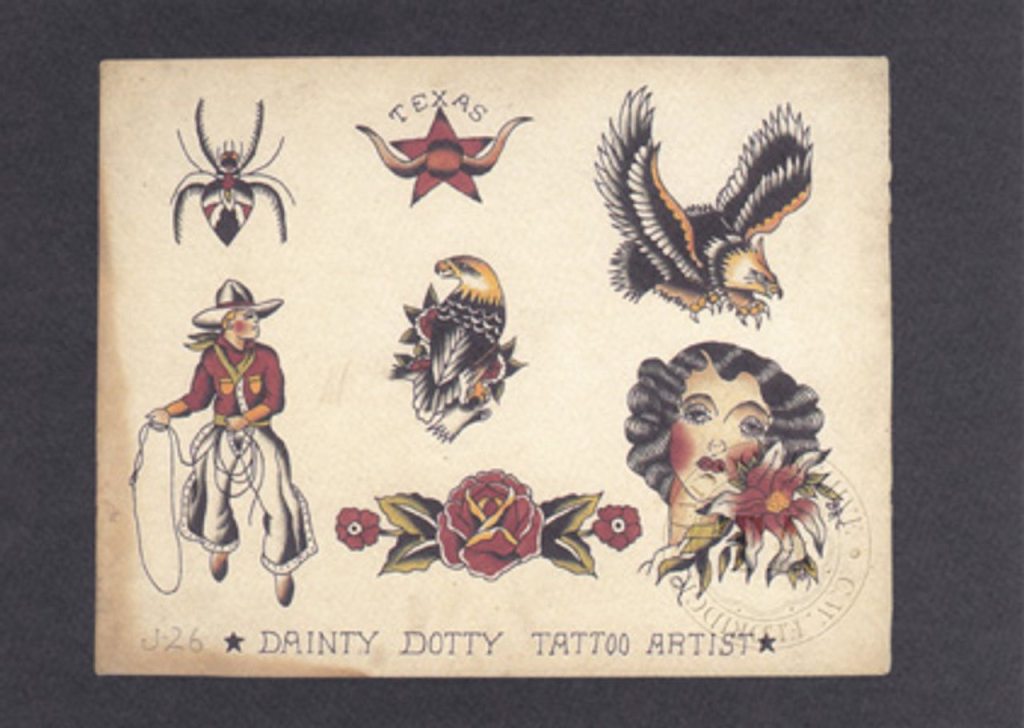

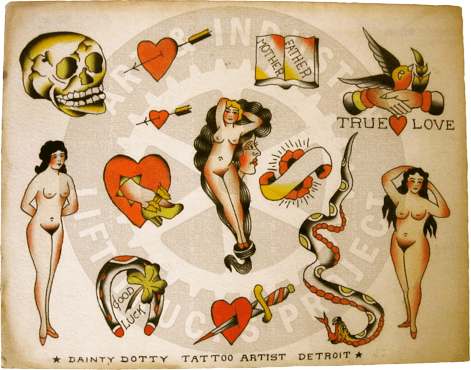

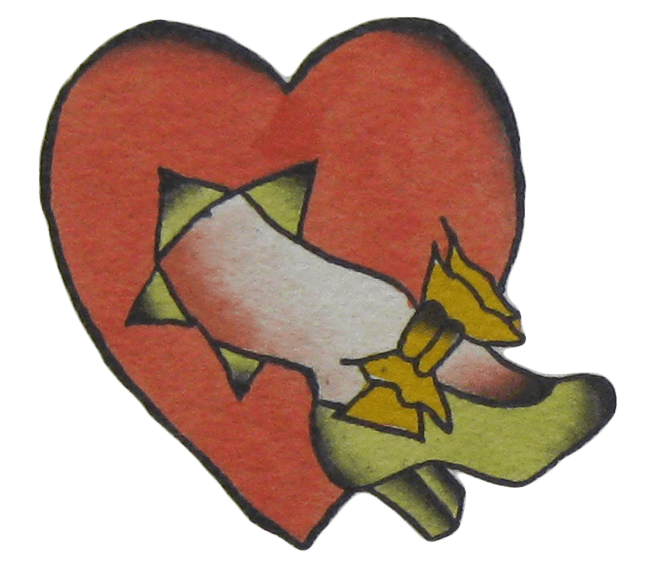

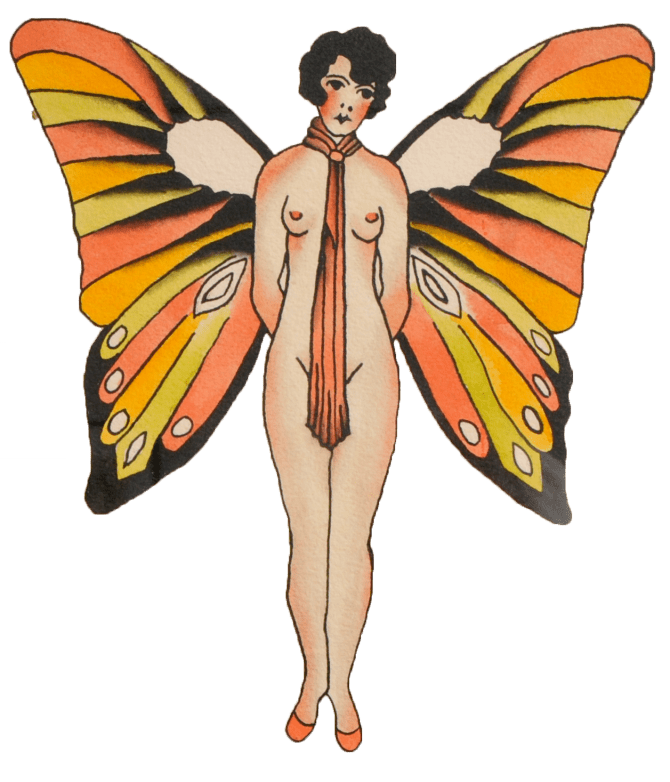

While no confirmed photographs” of “Dainty Dotty’s” tattoos survive, we do have documented drawings attributed to her hand — visual records that offer rare insight into her artistic style and technical skill.

These pages of flash include motifs typical of mid-century American Traditional tattooing: a butterfly-winged woman, heartbreak banners, and stylized nude pin-ups.

Her drawings also help confirm her role as a tattooer, not just a tattooed woman. In an era when fat women were rarely seen as artists — and even more rarely as tattoo artists — Dotty’s sketches stand as archival proof of her technical engagement with the craft. They are part of a lineage of women who shaped tattoo history from the margins, often without recognition or documentation.

Legacy Lives On

Florence “Dainty Dotty” Jensen remains an enigmatic figure — a woman whose body, art, and performance defied convention but whose later life slips quietly into obscurity.

Florence “Dainty Dotty” Jensen’s later years remain largely undocumented, a quiet fade from the spotlight she once commanded. What we do know is that she died of a heart attack on December 17, 1952, at the age of 43, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles — one of the city’s oldest and most culturally layered cemeteries. Established in 1877, Evergreen became a resting place for circus and carnival performers through the Pacific Coast Showmen’s Association, which dedicated a section in 1922 known as “Showmen’s Rest.”

Dotty’s life invites us to rethink who gets remembered, how stories are preserved, and what it means to archive a body that was both spectacle and site of creation. In every lace fan, every flash drawing, and every whispered memory of her inked skin, Dotty left behind a legacy that still challenges and inspires — especially for those of us committed to reclaiming histories that refuse to fit neatly in the margins.

Sources

- Owen Jensen

- Dainty Dotty – LIFT TRUCKS ART

- Buried in Evergreen’s Showmen’s Rest: “Dainty Dotty” Jensen – The Dead Bell

- https://www.bing.com/search?pglt=2339&q=”Dainty+Dotty”&cvid=0ddf769cbf774c1ab52e013c372ab81a&gs_lcrp=EgRlZGdlKgYIABBFGDkyBggAEEUYOTIGCAEQABhAMgYIAhAAGEAyBggDEAAYQDIGCAQQABhAMgYIBRAAGEAyBggGEEUYPDIGCAcQRRg8MgYICBBFGDzSAQgyMTYyajBqMagCALACAA&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=NMTS&ntref=1

- Buried in Evergreen’s Showmen’s Rest: “Dainty Dotty” Jensen – The Dead Bell

- No Land Tattoo Parlour

- Our History – Evergreen Cemetery

Leave a comment