In the late 1930s, as tensions escalated in East Asia and the United States edged toward war, a young woman named Lin Tsen Chan arrived in America under circumstances that newspapers described as harrowing. By the early 1940s, she was performing burlesque in San Francisco—an unlikely path shaped by global conflict, migration, and the racialized entertainment industry of the time.

From China to California

Lin’s story first appeared in U.S. newspapers around 1939. Reports varied in detail, but many described her as a refugee who had escaped political violence in China. Some accounts claimed she had been imprisoned or held against her will before managing to flee. These stories, while sensationalized, reflected the broader reality of Chinese nationals fleeing the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which devastated cities like Shanghai and Nanjing.

“Lin Tsen Chan, the Chinese girl who was captured by the Japanese as a spy and held prisoner. During her detainment she danced for the entertainment of the officers and won the admiration of all. She was smuggled aboard a ship and sent to Paris.” – Bradford Evening Star. “Beautiful Oriental Refugee at New Bradford Today.” Page 12. January 5, 1940

The Lancaster Eagle goes into a little more detail:

“Lin Tsen Chan was starring in a Shanghai Theatre when the war broke out. She was accused of being a spy and was held prisoner. During the time she was detained she entertained officers and soldiers of the Japanese army, won their admiration and proved to them that she was an entertainer and nothing more…She sets a part of her weekly salary aside each week to help her people in the war-torn Orient.” – Lancaster Eagle Gazette. Page 3. February 6, 1940

In Paris, Lin Chan is hired to perform at the Folies Bergere for a long run and then featured at the Casino de Paree. By 1940, Lin had made her way to San Francisco, a city with a growing Chinese American population and a booming nightlife scene. That same year, the Life magazine photo essay on the Forbidden City nightclub brought national attention to the city’s all-Asian floorshows. Lin was part of this emerging scene.

Performing at the Forbidden City

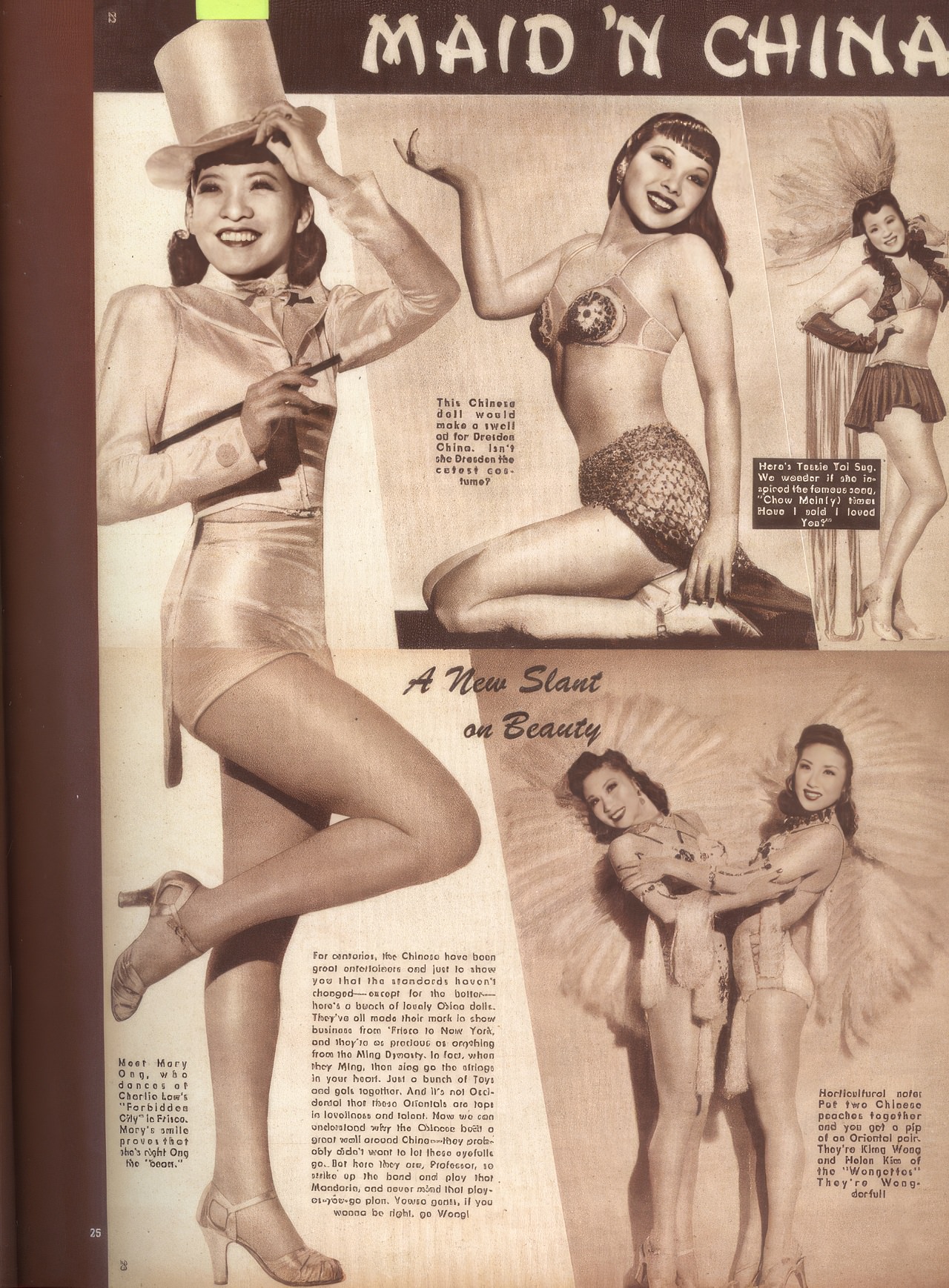

The Forbidden City nightclub opened on December 22, 1938, at 363 Sutter Street. Founded by Charlie Low, it was the most famous of several Chinese American nightclubs that catered to a mostly white audience. These venues—part of what came to be known as the “Chop Suey Circuit”—offered a mix of jazz, burlesque, and variety acts, all performed by Asian American entertainers.

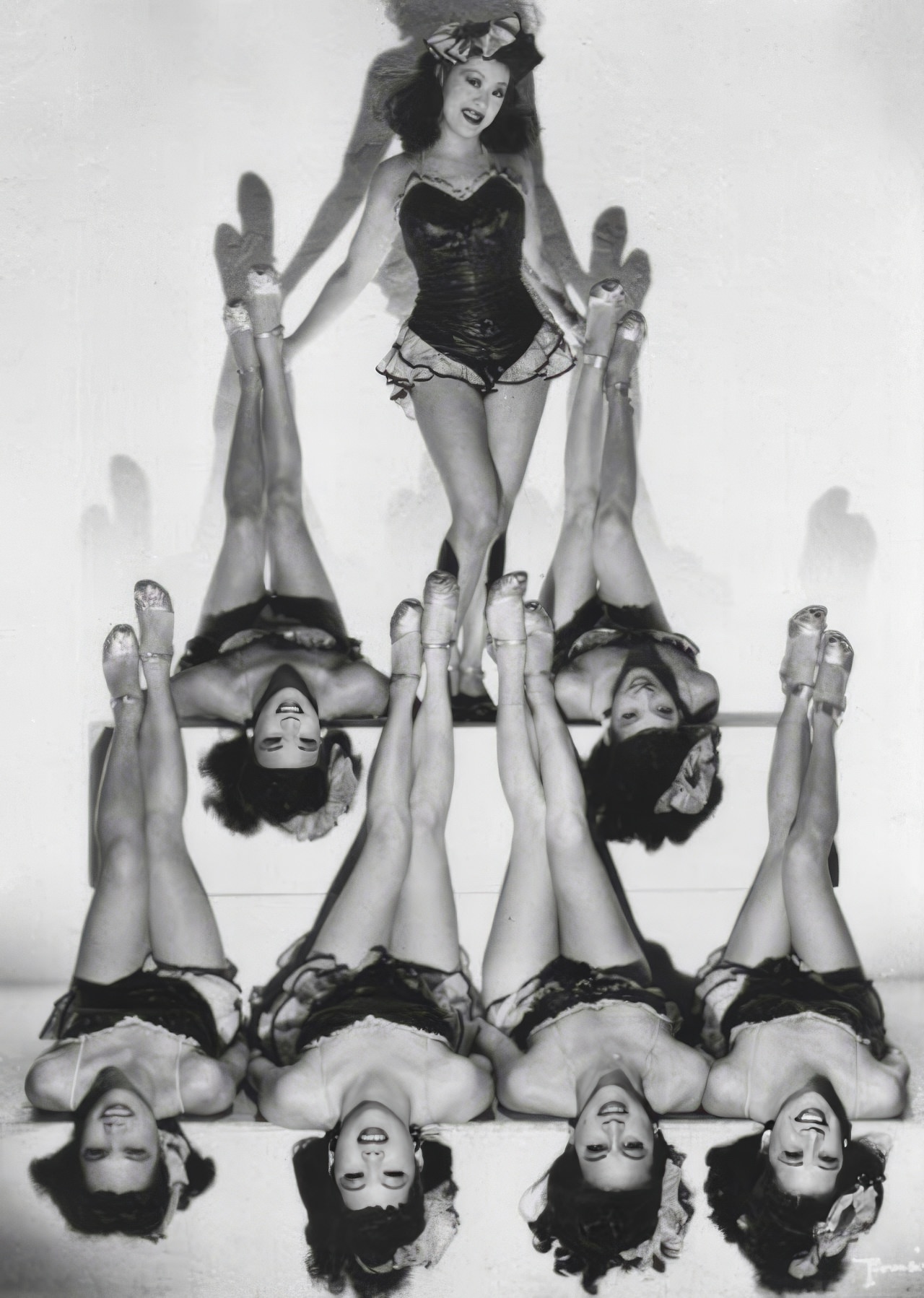

Lin joined the ranks of dancers and burlesque performers who worked at clubs like Forbidden City, Club Shanghai, and Kubla Khan. While many of her peers were second-generation Chinese Americans born in the U.S., Lin stood out as one of the few recent immigrants. Her presence added a layer of authenticity to the clubs’ “Oriental” branding, even as she performed in Western styles like jazz and rumba.

The Chop Suey Circuit

Similar venues like the Forbidden City began popping up all across the United States. The “Chop Suey Circuit” was a network of Asian American nightclubs that flourished in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York from the 1930s through the 1950s. These venues—most famously the Forbidden City in San Francisco—featured all-Asian casts performing Western-style entertainment, including jazz vocals, tap, fan dancing, and burlesque. For women like Lin Chan, the circuit offered rare opportunities to perform professionally, though often within the confines of exoticized stage personas. While the shows catered to white audiences and leaned into Orientalist aesthetics, performers brought skill, charisma, and agency to their acts, navigating a complex space between visibility and stereotype.

Lin Chan & Burlesque

Burlesque in the 1940s was a space of contradiction. For Asian women like Lin, it offered rare visibility and income—but also required navigating a minefield of racial and sexual stereotypes. Performers were often advertised with exoticized taglines, and audiences expected a blend of titillation and “foreign” mystique. Lin Chan was given the stage moniker “Daughter of China” and “The European Refugee Artist.”

Despite these pressures, Lin and her peers brought skill and charisma to the stage. They learned choreography from instructors like Walton Biggerstaff and performed multiple shows each night. Lin’s performances likely included fan dances, jazz routines, and striptease acts—styles popularized by stars like Noel Toy, who was dubbed the “Chinese Sally Rand.”

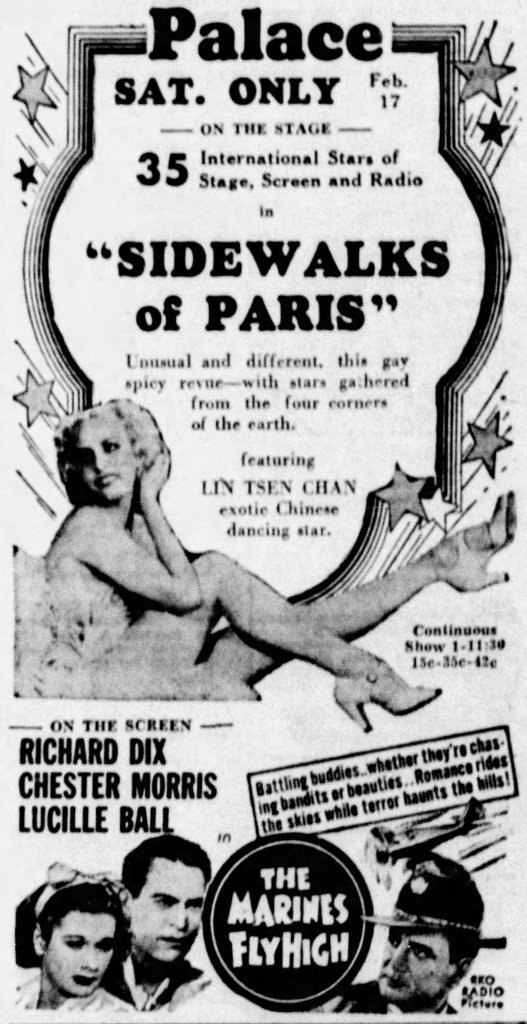

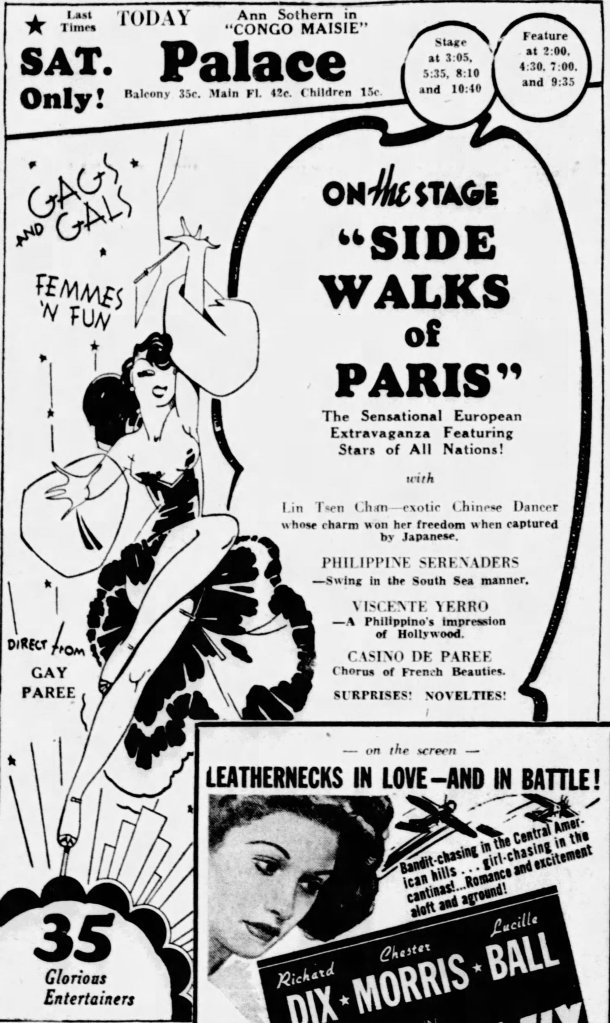

The Sidewalks of Paris

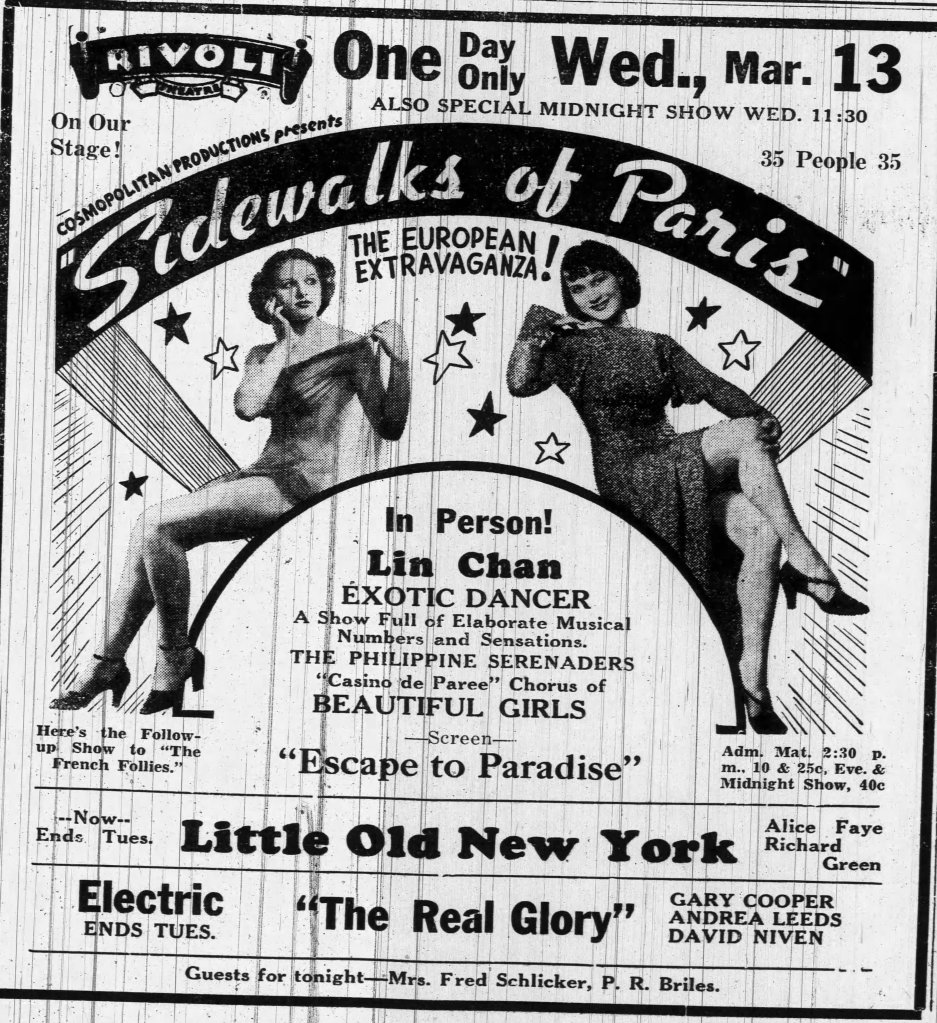

Lin Chan was the featured exotic dancer in the traveling revue “Sidewalks of Paris”. She was often billed as “The Girl Who Set the Japanese Soliders Daffy! She’s Different!” The show boasted 35 performers, 10 big acts, and a 10 piece Filipino band. The advertisements stated, “where You See People of All Nationalities…featuring Europe’s Stars of Radio, Stage, and Screen! Plus the Philippine Serenaders and the “Casino de Paree” chorus.”

The Ogden Standard Examiner reported, in March 1941, that Lin Chan had joined the Andre Girarduet company “after escaping from Japanese soldiers in her native land. Her dancing had captivated her guards, who aided her in getting out of China.”

Lin Chan in Falls City, Nebraska

In March 1940, “Sidewalks of Paris” came to the Rivoli Theater in Falls City, Nebraska. Lin Chan was billed as an exotic dancer. The moving picture “Escape to Paradise” was shown on screen.

Legacy and Historical Gaps

Lin’s name faded from the press after the mid-1940s. Like many performers of the era, she may have left the stage to pursue other work or raise a family. The postwar years saw a decline in Chinatown nightclubs, especially after the rise of topless bars in the 1960s. Forbidden City closed it’s doors in 1970.

Today, Lin Chan’s story survives in fragments—newspaper clippings, club programs, and oral histories. She remains a symbol of the resilience and adaptability of Asian women who found themselves on American stages during a time of war, migration, and cultural upheaval.

Sources

Newspaper Articles/Advertisements

- Bradford Evening Star. “Beautiful Oriental Refugee at New Bradford Today.” Page 12. January 5, 1940

- Lancaster Eagle Gazette. Page 3. February 6, 1940

- The Falls City Journal. Ad for Lin Chan at the Rivoli Theatre. Page 2. March 12, 1940

- The Falls City Journal. Ad for “Sidewalks of Paris” at the Rivoli Theatre. Page 2. March 11, 1940

- Palladium Item. Ad for Lin Chan at the Indiana Theatre. Page 11. January 26, 1940

- The Marion Star. Ad for “Sidewalks of Paris” at the Palace Theatre.” Page 10. February 16, 1940

- The Marion Star. Ad for Lin Tsen Chan at the Palace Theatre. Page 11. February 14, 1940

- The Ogden Standard Examiner. Page 10. March 5, 1941

- The Ogden Standard Examiner. “Parisian Revue is Stage Offering.” Page 10. March 5, 1941

- The Ogden Standard Examiner. “Stage Program Wins Applause.” Page 12. March 6, 1941

- The Sandusky Register. “Revue Booked.” Page 2. February 1, 1940

Websites

- Behind the Curtain of the 1940s Chinatown Nightclubs that Shattered Asian Stereotypes

- The Glorious History of the Forbidden City, America’s Chinese Nightclub Gem

- Chop Suey Circuit & China Doll Nightclub – Museum of Chinese in America

- The Glorious History of the Forbidden City, America’s Chinese Nightclub Gem

Leave a comment