Burlesque in Des Moines during the mid‑20th century was caught in a fascinating tug‑of‑war between repression and resilience. From the 1950s through the 1990s, performers and venues navigated shifting city ordinances, police crackdowns, and moral crusades that sought to stamp out “immoral entertainment.” Yet despite raids, licensing battles, and the stigma of striptease, burlesque endured—sometimes underground, sometimes reinvented—reflecting both the city’s appetite for spectacle and its anxieties about sexuality and public decency. This era reveals not only the persistence of performers who kept the art alive, but also the cultural tensions that shaped Des Moines’ nightlife, making it a microcosm of America’s broader struggle with censorship, liberation, and performance art.

1950s

In the 1950s, Des Moines enforced strict “immoral entertainment” ordinances that targeted burlesque, striptease, and other sexually suggestive performances. These laws often fell under public decency or anti-vice regulations, which prohibited nudity, “indecent exposure,” and performances deemed lewd or lascivious. Burlesque shows were frequently raided, denied licenses, or forced to tone down acts to avoid being classified as obscene.

Des Moines municipal codes in the mid-20th century banned “indecent exposure” and “immoral exhibitions.” While not naming burlesque directly, these laws were applied to burlesque houses and cabarets. Iowa’s obscenity statutes criminalized “lewd and lascivious acts” in public. This gave local authorities legal grounds to prosecute performers or venue owners.

Performers often emphasized comedy, parody, or musical elements to avoid being classified as obscene. Costuming and choreography were carefully managed to stay within legal limits. Newspaper archives from the Des Moines Register in the 1950s document raids on burlesque clubs, arrests of dancers, and public debates over “smut shows”. Despite restrictions, burlesque remained popular. Audiences sought out risqué entertainment, creating a push-pull between demand and moral regulation.

Why This Matters

The 1950s laws in Des Moines reflect a broader national pattern: burlesque was caught between being a legitimate theatrical tradition and being criminalized as obscenity. These restrictions shaped how performers presented themselves and how venues operated, laying the groundwork for later revivals when attitudes toward sexuality and performance loosened.

1960s

By the 1960s, Des Moines’ relationship with burlesque had shifted from outright suppression to uneasy coexistence. The city still carried the moral weight of the previous decade’s crackdowns, but cultural winds were beginning to change. Nationally, the sexual revolution and loosening censorship laws created space for more daring performances, and locally, clubs experimented with blending striptease, comedy, and live music to attract audiences while skirting “immoral exhibition” ordinances. Police raids and licensing battles didn’t disappear, yet performers found new ways to push boundaries—sometimes through parody, sometimes through spectacle—that reflected both the era’s rebellious spirit and the city’s cautious embrace of modern nightlife.

Blue Garter Club | Radolph Hotel

In 1965 the Blue Garter Nightclub was a favorite with convention goers because of its exotic dancers. The entertainment was routy and that caused a problem for the city council. In July 1965, the Des Moines city council voted 5-0 to deny the renewal of the Blue Garter Club’s liquor license based on the “obscene” and “immoral” entertainment.

Councilman George Nahas described the entertainment within the Radolph Hotel nightclub.

“The entertainment is supposed to be so-called exotic dancing. From the information I have, it was filthy dancing.” (The Gazette. “D.M. Night Club Denied Licenses.” Page 5. July 20, 1965)

Nahas also asked for a full-scale investigation into other clubs in Des Moines, like the New Orleans Club, which also featured exotic dancers.

1970s

The 1970s ushered in a new era for burlesque in Des Moines, one shaped by the broader currents of the sexual revolution. As censorship laws loosened and cultural attitudes shifted, performers gained unprecedented freedom to explore erotic expression on stage. Yet with this new exposure came a double‑edged reality: alongside innovative artistry and bold experimentation, the decade also saw an explosion of sexploitation, where commercialized nudity and sensationalism often overshadowed burlesque’s wit, parody, and theatrical roots. In Des Moines, clubs and theaters reflected this tension—some embraced the liberatory spirit of the times, while others leaned into shock value, blurring the line between empowerment and exploitation.

Newspaper reports from the 1950s–70s in Des Moines tended to describe “stripteasers” or “burlesque dancers” generically, without naming them. This was partly due to stigma and partly to protect identities. Some well-known burlesque stars (e.g., Tempest Storm, Ann Corio) toured through Iowa in the 1960s–70s, but documentation of them specifically performing in Des Moines is sparse. Touring performers often passed through Midwestern cities, but local press coverage was inconsistent.

Century 21 Shows at Iowa State Fair

By 1975, Al Kunz was no stranger to the Iowa State Fair—he had been bringing his shows to the midway for fourteen consecutive years. That longevity gave him credibility as both a carnival veteran and a preservationist of old-time burlesque. His decision to stage a “clean” Century 21 burlesque show that year wasn’t just about nostalgia; it was about protecting a tradition he felt was being lost to the flood of X‑rated films and increasingly explicit strip clubs.

Kunz’s fourteen‑year streak underscored his commitment to keeping burlesque alive in a changing cultural landscape. For fairgoers, especially those from small towns, his show offered a rare chance to see burlesque framed as comedy and spectacle rather than pure exposure. In that sense, Kunz’s presence at the fair was both continuity and resistance—an effort to remind audiences that burlesque had roots in wit, tease, and theatricality long before it was overshadowed by sexploitation.

By staging burlesque in a family-friendly setting, he invited small-town fairgoers to experience the genre as it once was: playful, cheeky, and rooted in vaudeville tradition. In doing so, he preserved a slice of performance history that was rapidly vanishing from the American stage. His efforts remind us that burlesque in the 1970s wasn’t just evolving—it was splintering. Some leaned into liberation and explicitness; others, like Kunz, clung to the tease, hoping audiences might still crave a wink over a flash.

“The Best Burlesque” Show | Ingersoll Dinner Theater

The Ingersoll Dinner Theater hosted a traveling burlesque show multiple times between August 1975 and 1986 called “The Best of Burlesque.” Dave Hanson, the producer of the traveling show, insisted there was no stripping but more satirizing popular theater. The company performed in Des Moines three times between 1984 and 1986, all at the Ingersoll Theater.

“We’re PG-13,” he told the Des Moines Register, “You won’t hear any word stronger than a ‘hell’ or a ‘damn’. I see to that. What you’re going to hear a lot of is double-entendre humor. We feature all elements of burlesque, but we lean heavily on the comedy.”

Created in 1972, “The Best of Burlesque” boasted a company of 13 and a full schedule of 10 months a year performing across the country. At this time, 1984, they were one of two traveling companies in the nation! Sandy O’Hara was the star and the other top performer was Clarence Loos, “the man of 1,000 faces.” Nostalgia and hilarious comedy were main themes in the show. Dee Hengstler was another dancer who would give a “classy strip” in her act, The Dance of the Seven Veils.

Sandy O’Hara

The star of “The Best of Burlesque” was Sandy O’Hara, Dave Hanson’s wife, who had a great shape and a comedic flair. Sandy had a fan dance tribute to Sally Rand, in which she performed partially nude behind large feather fans. Her acting ability was mentioned more than once in the newspapers, where she was compared to Red Skelton, Abbott & Costello, and Fanny Brice.

Sandy O’Hara got her start in show business as a chorus girl in 1966 at 19 years old. She left her secretarial job when she met Dave Hanson. They soon married. Sandy started her own striptease act and was immediately booked in “Minsky’s Burlesque Follies” at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas. Sandy was selected as “Miss Armed Forces” in the early 1970s (Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe were also given this title). She received and responded to more than 13,000 letters from servicemen. The Air Force presented her a proclamation declaring her the official “Miss Pin Up of the Vietnam Conflict” for ‘her unselfish devotion to the cause of elevating morale among the troops.” She would visit them anytime she was performing near a VA hospital.

Sandy was no stranger to TV and film. She acted in the TV series “Vegas” and an NBC movie “Pleasure Palace” and the film “Looking to Get Out” with Ann-Margaret and Jon Voight.

1980s

By the 1980s, burlesque in Des Moines found itself competing with an increasingly commercialized adult entertainment industry. The glamour and parody that once defined the art form were often overshadowed by the rise of strip clubs and video pornography, which promised faster thrills and more explicit content. Yet burlesque did not disappear—it adapted. Some venues leaned into nostalgia, reviving classic routines with rhinestones and camp, while others blurred the line between burlesque and modern striptease to stay relevant. Against the backdrop of Reagan‑era conservatism and a booming nightlife economy, Des Moines’ burlesque scene reflected both resilience and reinvention, holding onto its theatrical roots even as audiences were tempted by the era’s more sensational offerings.

This frames the 1980s as a decade of competition and adaptation, showing how burlesque survived by carving out its own niche amid the rise of sexploitation and mainstream adult entertainment.

B.J.’s Lounge | 5175 N.W. 6th Drive

B.J.’s Lounge was known for exotic dancers and topless bar maids. They came under fire in September 1983 when police discovered a waitress with just 1-inch square transparent Band-Aids covering her nipples and one exotic dancer with completely uncovered nipples.

The owner of B.J’s, Bradford James Dindorf, was charged and convicted of “allowing indecent public exposure in a liquor establishment.” A Polk County district judge ruled there was uncontradicted testimony that Dindorf allowed exotic dancers to perform with transparent nipple coverings. Dindorf’s defense attorney, James Piazza, argued that flesh-colored tape covered the nipples and that met the law’s requirements. Piazza pointed out a distinction in the law on public exposure:

‘Clearly, the Legislature made a voluntary and intelligent decision in prohibiting a waitress from exposing any part of her breast and in allowing a performer to expose all of her breast, except her ‘breast nipple’.”

Judge Elliot rejected the argument, stating transparent tape doesn’t constitute sufficient coverage under the law. In his ruling he stated, “To be covered…it must be an opaque substance, which in fact, does not allow that portion or that thing to be covered to be seen by the naked eye.” – Des Moines Register. “Judge covers law on cover-up.” Melinda Voss. Page 14. January 6, 1984

The Good, Bad, and Ugly Lounge + The J&R Lounge

Four people were arrested in July 1981 at the Good, Bad, and Ugly Lounge (5325 2nd Ave.) in Des Moines. They were charged with indecent exposure and pleaded not guilty. Jan Marie Vanvleet was just 24 years old when she was arrested during the raid by plain-clothes deputies from the Polk County Sheriff’s Office and uniformed officers from the Iowa State Patrol. That same evening dancers were arrested at the J & R Lounge (5102 2nd Ave). Reports of nude dances being performed at the taverns caused quite the stir!

The managers of the lounges were charged with counts of permitting indecent exposure. Bonnie Lynn Doering, 29, of Fremont, NE was arrested and charged. Rumor had it that nude dances continued at the establishments, but no further arrests occurred.

The Cave Lounge was a go-go club presenting continuous nude dancers from 3:30pm to 1:30am, on North 2nd Avenue.

1990s

In 1990, Des Moines’ regulation of nude dancing reflected a broader national debate over whether erotic performance counted as protected expression under the First Amendment. At the time, Iowa already restricted nude dancing in bars that sold alcohol, a measure aimed at curbing “barroom-style” strip shows. These local rules were reinforced by national developments: in October 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear a case from Indiana that questioned whether states could outlaw all nude dancing in bars, even when performances were not obscene. The Court had previously acknowledged that nude dancing carried some expressive value, but only “marginal” protection, meaning municipalities like Des Moines could impose significant restrictions so long as they claimed a public interest in morality or order.

By 1991, just north of Des Moines city limits, patrons could frequent 6 different bars that featured “scantily clad dancers” on stage. That same year, County Supervisor Robert Kramme went on a crusade against strip joints, citing violations of Polk County’s zoning ordinance and attempting to enforce strict clothing for dancers and limit their movements among the audience.

This climate set the stage for Iowa’s later 1997 law, which banned nude dancing in any business with a sales tax permit—except those classified as theaters or art centers. In short, by 1990 Des Moines dancers were already navigating a precarious legal landscape, where their work was treated less as art and more as a public nuisance subject to regulation.

Big Earl’s Goldmine

n the late 1990s and early 2000s, Des Moines, Iowa, found itself at the center of a heated cultural and legal debate—one that blurred the lines between erotic performance, artistic expression, and municipal control. At the heart of this controversy stood Big Earl’s Goldmine, a strip club just north of city limits, whose neon-lit stages became both a sanctuary and a battleground for dancers asserting their right to perform nude.

Tracy Bedford | Nude Dancer

Tracy Bedford, a 23-year-old nude dancer at Big Earl’s Goldmine in Des Moines, testified before a federal judge to challenge a new Iowa law banning nude entertainment in venues that serve alcohol. Represented by the Iowa Civil Liberties Union, Bedford argued that her performances are a form of artistic expression and personal freedom. She emphasized her pride in her work, the financial investment she’s made in costumes $10-$15k ($21,610.11-$32,415.17 in today’s buying power), her commitment to performing 4-5 times a week, and her role as a single mother supporting a young child.

Club operator Ronald Farkas also testified, warning that the law would devastate businesses like his. The case centers on First Amendment rights and the tension between public morality legislation and performers’ autonomy.

Crime at The Outer Edge Nightclub

Exotic Dancer Delona Webster was working as an exotic dancer at the Outer Edge Nightclub in Des Moines. She met Jerry Dean one evening at the Outer Edge in 1998. The two agreed to meet up at his apartment after her shift. She was escorted by her boyfriend, though, Michael Weatherspoon, who eventually stabbed and killed Jerry Dean in a brutal attack. Michael testified he believed he was in imminent danger of death, so he grabbed a knife and stabbed Dean 14 times, before stealing his wallet and fleeing the crime scene. Delona was the only witness. She testified she believe Michael acted in self-defense. Dean was 55 years old and suffered from many health issues, making it difficult for him to defend himself. The jury charged Weatherspoon guilty of first-degree murder.

Mini East Theatre

The Mini East Theatre, located at 418 E. Locust St., was an adult theatre, arcade, and club. It sold novelties and had live dancers on stage 5 times a night.

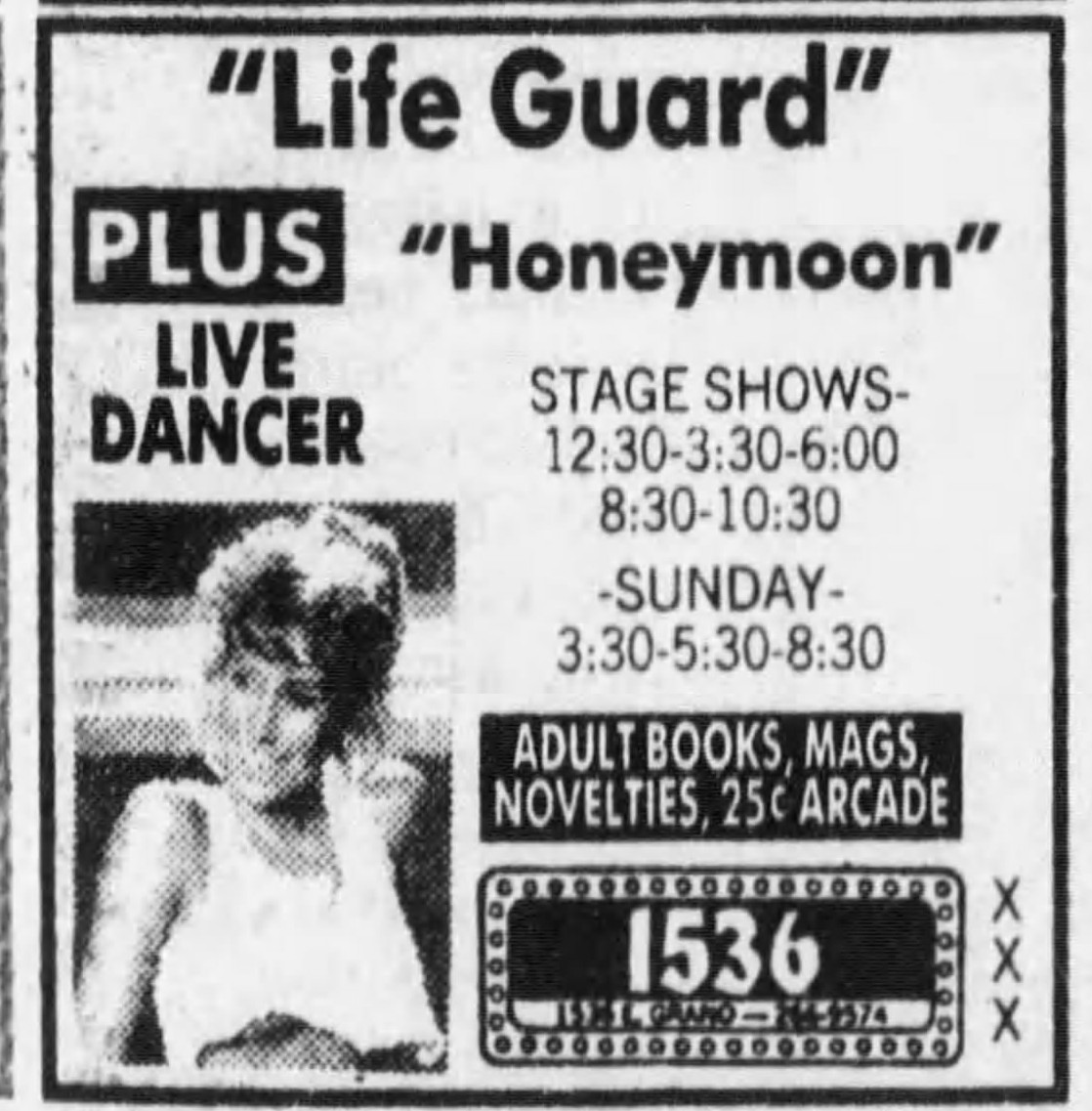

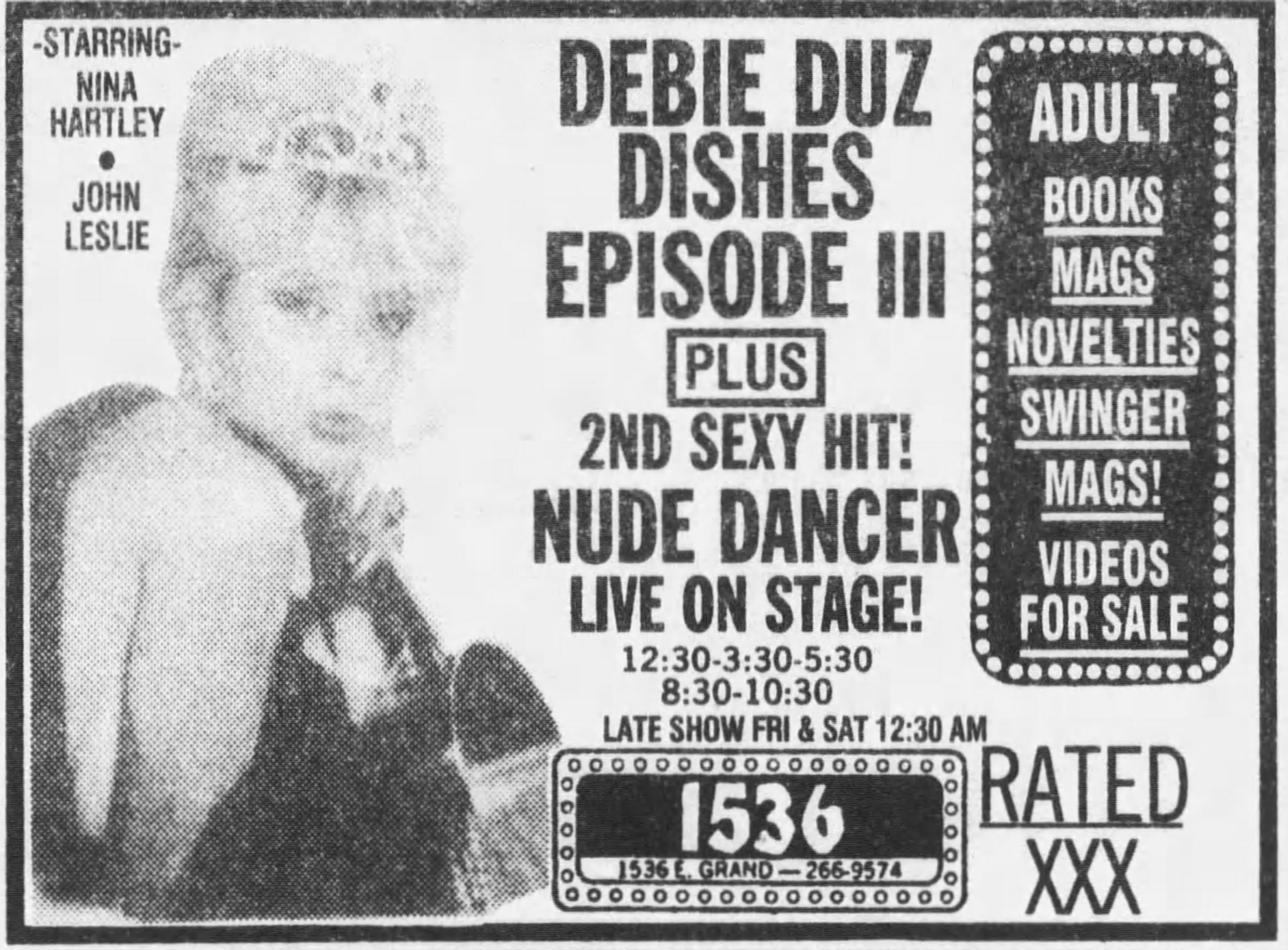

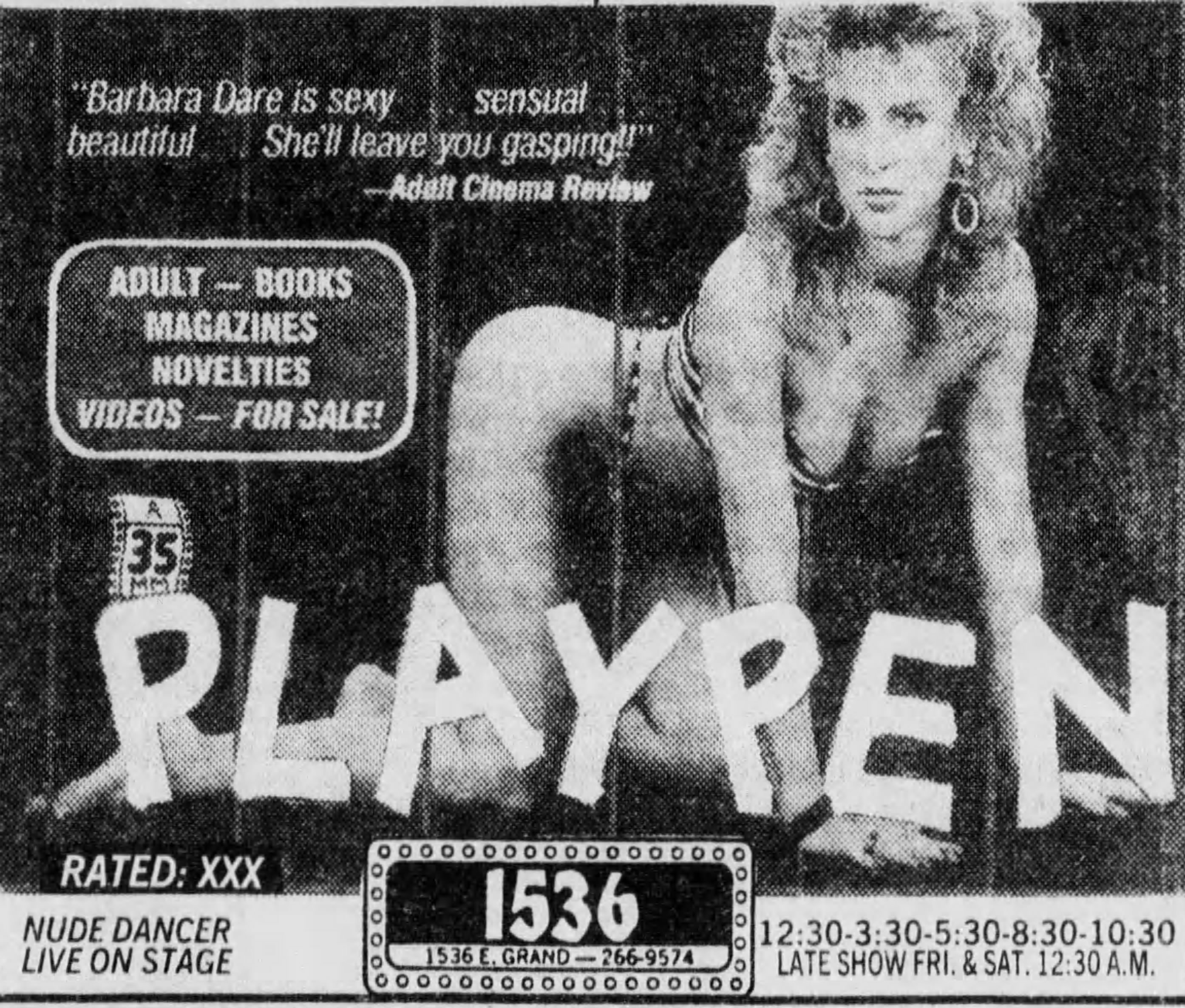

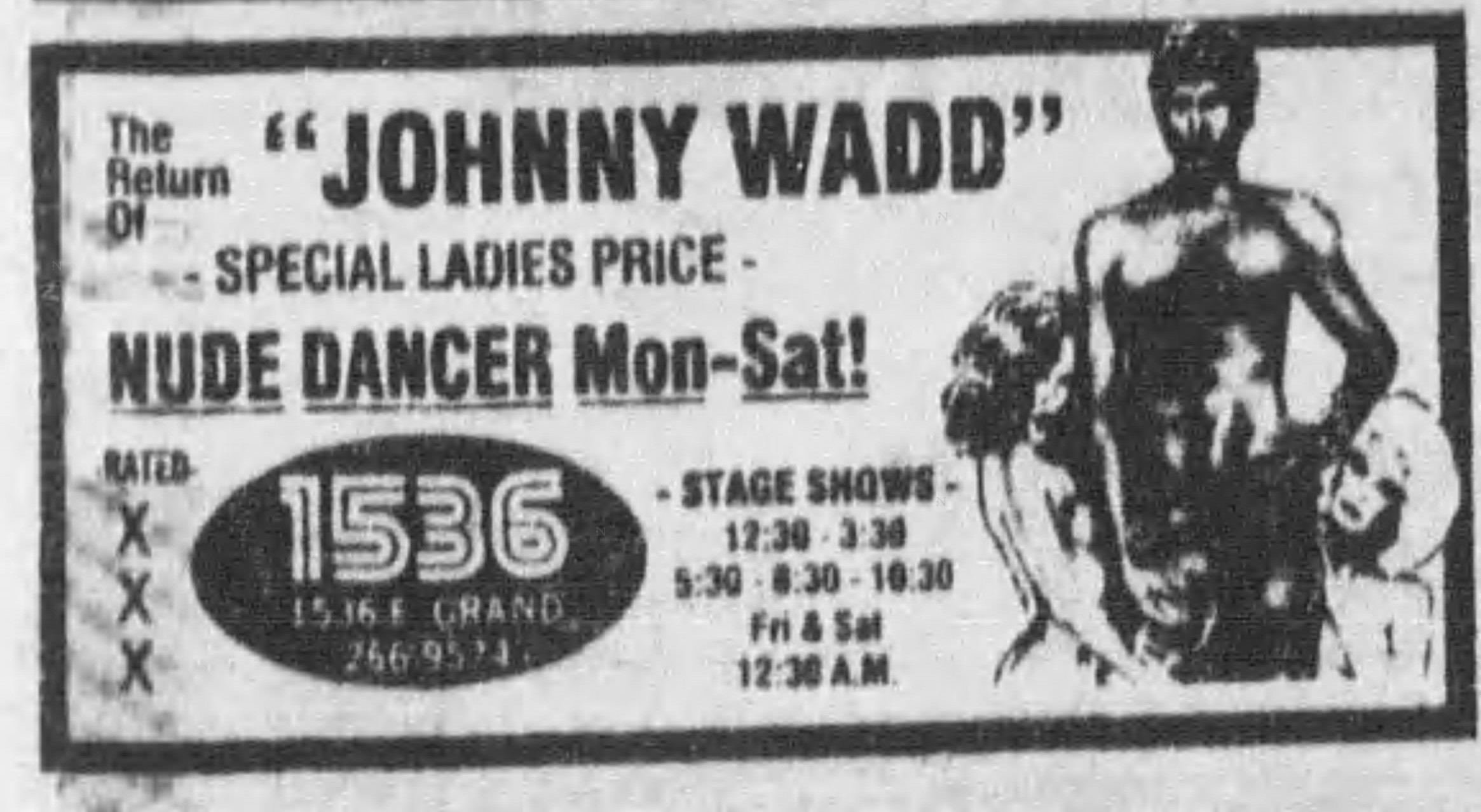

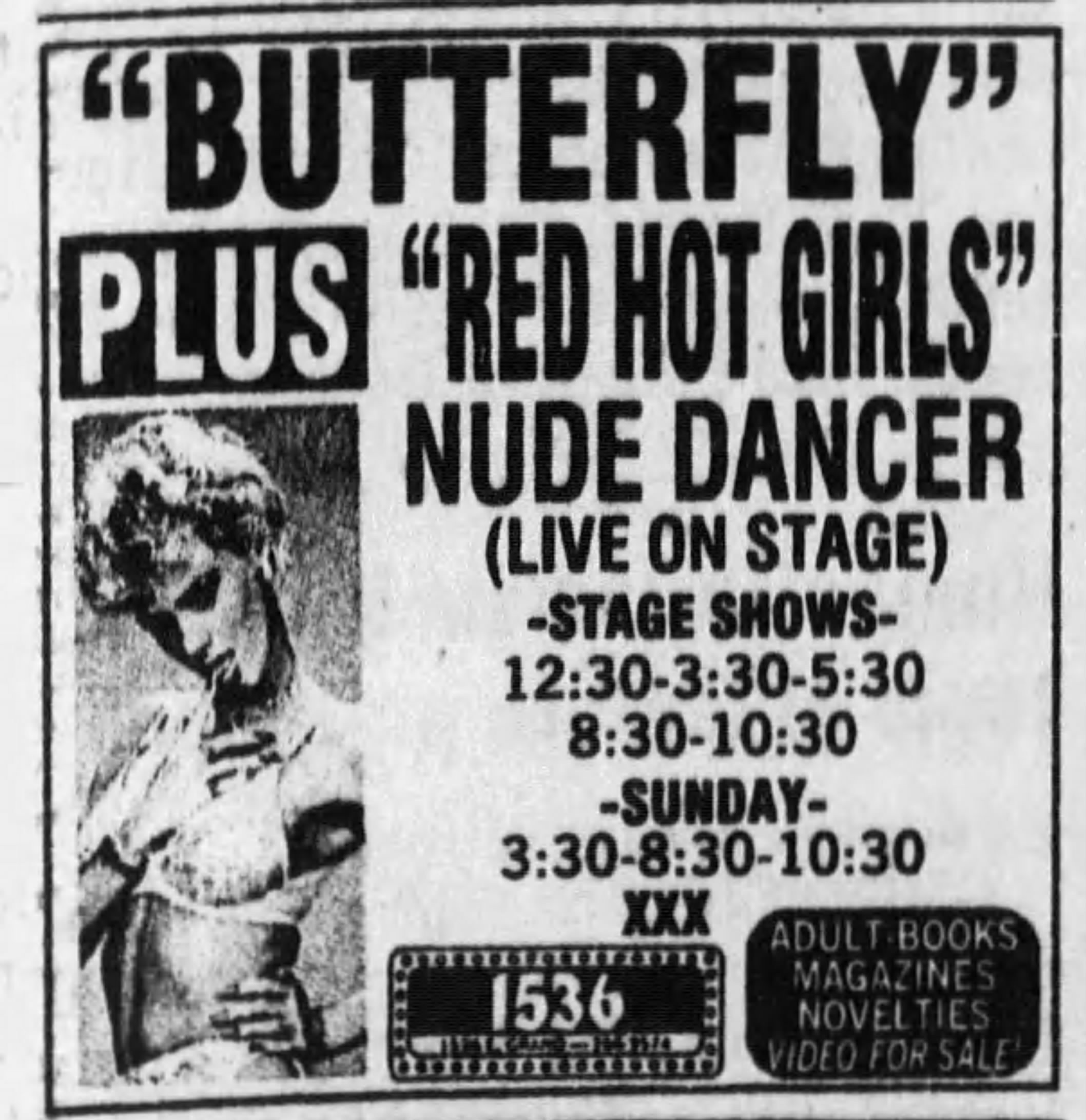

The 1536 Club

The 1536 Club had a dedicated stage for live dancers in addition to a screen for showing movies. It acted as a XXX Adult Theatre and Strip club. It opened in 1982 at 1536 E. Grand St. They also solde

Stage shows were at 12:30pm, 3:30pm, 6:00pm, 8:30pm, and 10:30pm, with late shows at 12:30am Friday and Saturday. The 1536 Club also sold adult books, magazines, videos, and novelties.

Here is an inconclusive list of performers that graced the stage of 1536:

- Cagney & Stacey

- Johnny Wadd

- Barbara Dare

- Cassie

- Rebecca Steele

- Jessica Laine

- Nikkie Wilde

- Lindsay

- Butterfly

- Red Hot Girls

- Pink Baroness

A Crime at 1536

In a bizarre and violent incident at the 1536, a dancer named Dana Westphal was assaulted just before her performance. The thief, later identified as Donald E. Graves, entered her dressing room and attempted to steal several personal items—including a sheer negligee, G-string, camera, and radio. When Westphal confronted him, he punched her and fled through a back door into an alley.

The escape didn’t last long. A theater employee, joined by several bystanders, chased Graves down and caught him about a block away. He was arrested and charged with aggravated burglary. Police noted that Graves would be questioned in connection with other recent thefts targeting nude dancers’ dressing rooms, suggesting a troubling pattern of harassment and theft within Des Moines’ adult entertainment venues.

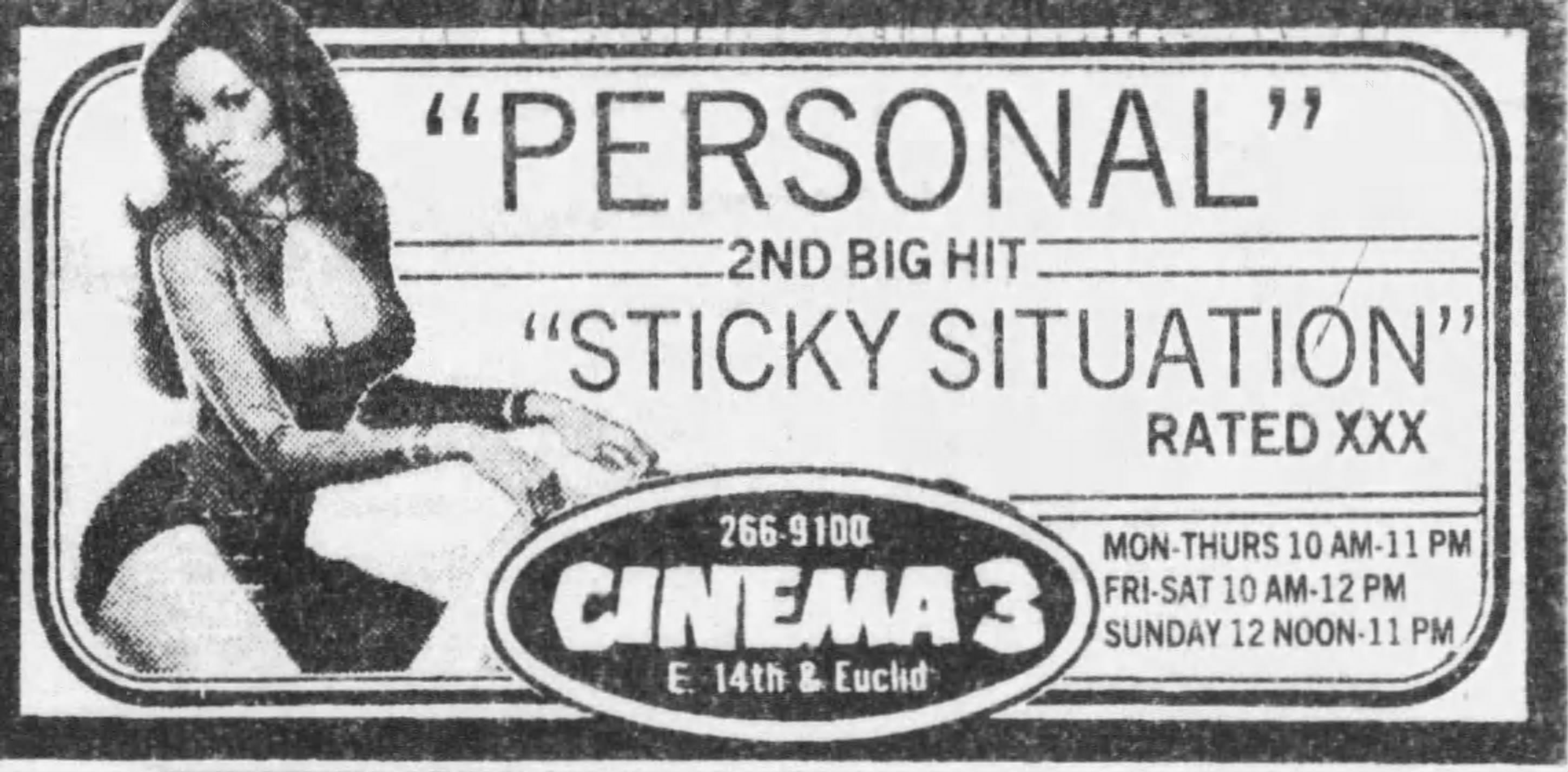

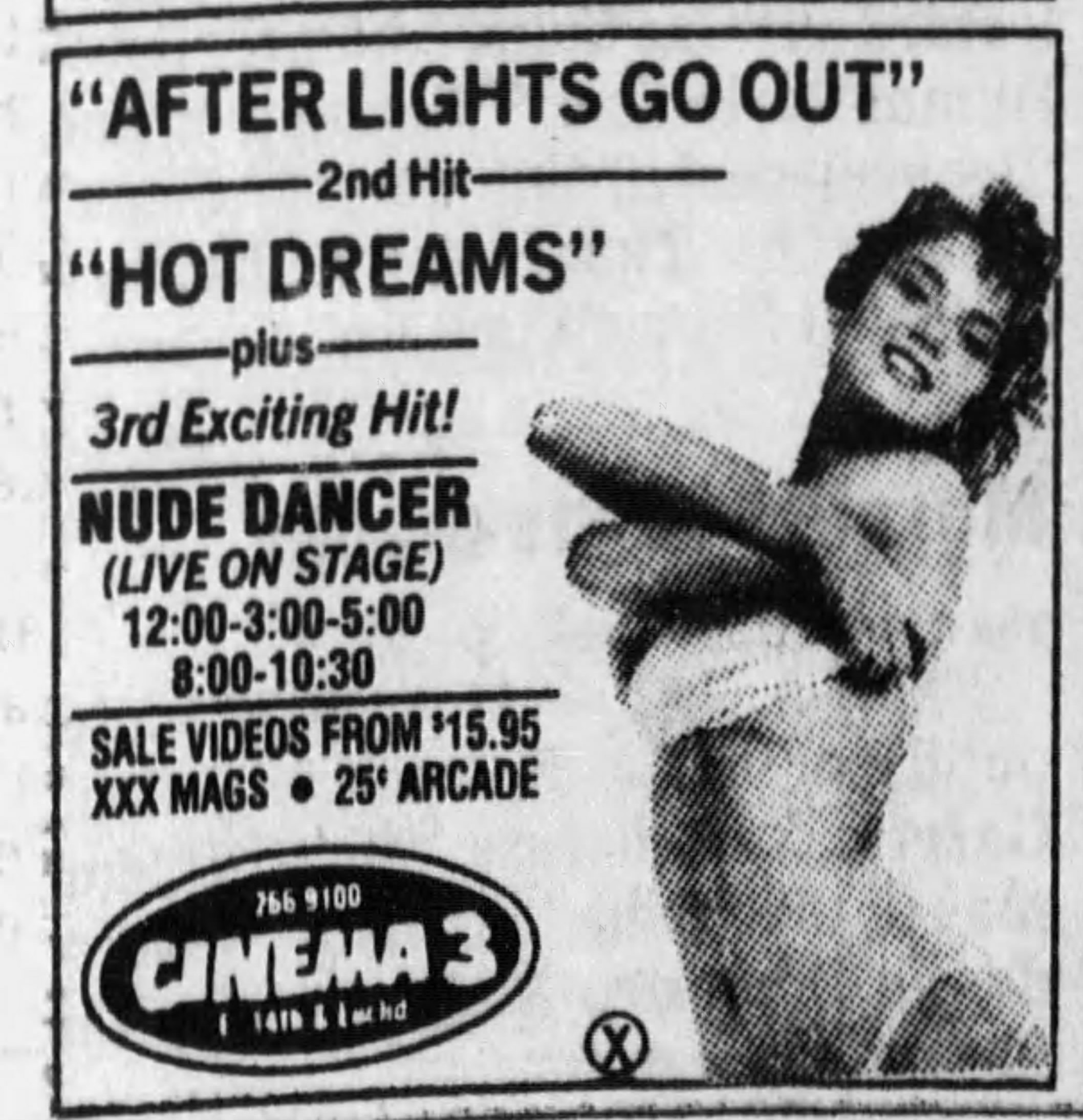

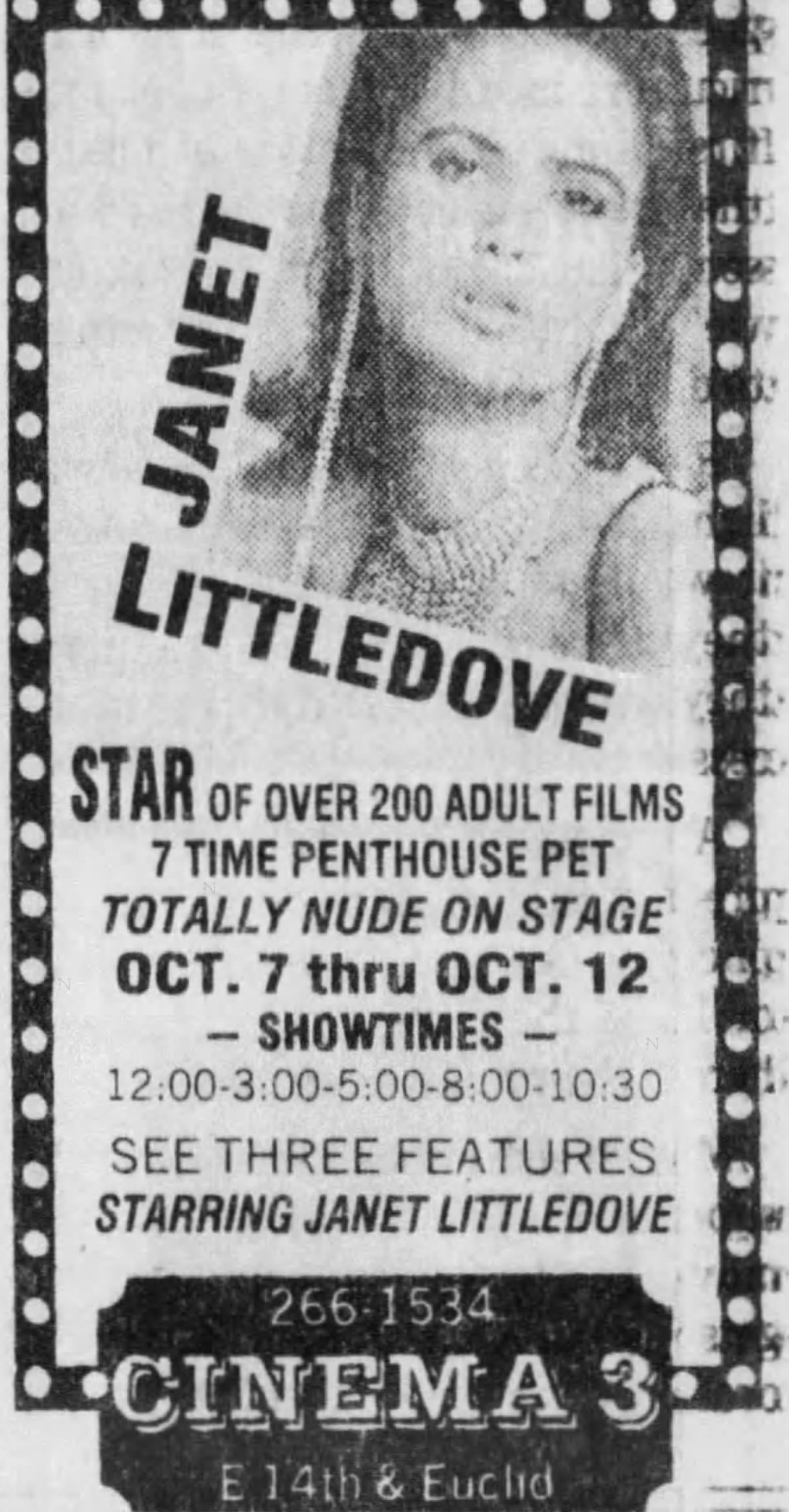

Cinema 3

The Cinema 3 Theatre opened around 1986 at E. 14th & Euclid and showed 3 movies on screen and live nude dancers on stage. Like other venues, they also sold adult magazines and videos. Dancing continued until 1992.

Burlesque Continues Today

From the 1950s through the 1990s, burlesque in Des Moines mirrored the nation’s shifting attitudes toward sexuality, censorship, and performance. What began as a tightly policed art form—raided, restricted, and often dismissed as “immoral entertainment”—slowly evolved into a contested space where tease, parody, and spectacle wrestled with the rise of strip clubs, sexploitation, and mainstream adult media. Each decade carried its own tension: repression in the 1950s, transition in the 1960s, overstimulation in the 1970s, adaptation in the 1980s, and survival into the 1990s.

Yet through all of this, burlesque never truly disappeared from Des Moines. It persisted in fairground shows, nightclub revivals, and the memories of performers who refused to let the tradition fade. More than just entertainment, burlesque became a lens through which the city’s cultural anxieties and desires were expressed. By tracing its arc across these decades, we see not only the decline and reinvention of a performance style, but also the resilience of an art form that continues to inspire new generations of performers and audiences today.

Burlesque it thrives today in Des Moines. Monthly shows, themed cabarets, and a growing network of performers keep the tradition alive, blending classic tease with contemporary creativity in what is known as neoburlesque. What was once policed as ‘immoral entertainment’ is now celebrated again as a vibrant art form, proof that burlesque in Des Moines has always been resilient, and continues to reinvent itself for new generations

Sources

- Evening World Herald. “Exotic Dance Brings Liquor Permit Loss.” July 21, 1965

- The Gazette. “D.M. Night Club Denied Licenses.” Page 5. July 20, 1965

- The Des Moines Register. “‘Frilly things’ taken as robber punches dancer.” Tom Suk. Page 25. October 7, 1982

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cagney & Stacey at 1536. Page 15. June 3, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Johnny Wadd at 1536. Page 67 June 29, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Debie Duz Dishes Episode III. Page 48. August 27, 1987

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Playpen at 1536. Page 66. November 26, 1987

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for 1536. Page 50. May 8, 1988

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for “Butterfly” and “Red Hot Girls” at 1536. Page 13. December 5, 1989

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for “Pink Baroness” at 1536. Page 16. December 8, 1989

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for 1536. Page 16. September 19, 1990

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for 1536. Page 18. October 9, 1991

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for 1536. Page 7. April 18, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Jessica Laine at 1536. June 18, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for 1536. Page 21. June 22, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Nikki Wilde at 1536. Page 30. July 7, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Rebcca Steele at 1536. Page 30. August 15, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. “Judge covers law on cover-up.” Melinda Voss. Page 14. January 6, 1984

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for the Cave. Page 71. March 30, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. “Old-time burlesque show planned for state fair.” Page 25. July 27, 1975

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 71. March 30, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 67. June 27, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 49. August 27, 1987

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 13. December 5, 1989

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 16. December 8, 1989

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 16. September 19, 1990

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 18. October 9, 1991

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 22. October 28, 1991

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 6. February 24, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 7. April 18, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 21. June 22, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Cinema 3. Page 30. August 15, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. “Burlesque going the way of all flesh.” Patrick Lackey. Page 9. August 17, 1975

- The Des Moines Register. “Las Vegas troupe will ‘be putting you on’ as Ingersoll presents burlesque shows.” Valerie Monson. Page 47, 52. September 27, 1984

- The Des Moines Register. “Burlesque not so naughty but nice.” Barbara Croft. Page 18. August 21, 1985

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Burlesque at Ingersoll Theater. Page 51. September 30, 1990

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Ingersoll Theater. Page 22. October 28, 1991

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Ingersoll Theater. Page 21. June 22, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. “Sandy O’Hara: Last queen of burlesque.” Bart Haynes. Page 11D. October 16, 1986

- The Des Moines Tribune. “Woman enters plea in exposure case.” John Lancaster. Page 9. August 1, 1981

- The Gazette. “Appeal rejected in Mason City murder.” Page 16. March 30, 2000

- The Des Moines Register. “‘Sexist’ Entertainment Practices Deplored.” Judith McManus letter to the editor. Page 8. March 7, 1973

- The Des Moines Register. “Rest easy: ‘Juice bars’ targeted.” Page 10. March 17, 1994

- The Des Moines Register. “Ethics tub is half full.” Page 7. July 1, 1996

- The Des Moines Register. “Juice Bars.” Page 1. July 10, 1997

- The Des Moines Register. “Too prude for nude? Don’t go.” Walter Wiese. Page 8. August 26, 1997

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Big Earl’s Gold Mine. Page 10. November 24, 1993

- The Des Moines Register. “Proud nude dancer: It’s my right.” Jonathan Roos. Page 1. August 20, 1997

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Varsity Theater. Page 50. May 8, 1988

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Varsity Theater. Page 18. October 19, 1991

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Varsity Theater. Page 21. June 22, 1992

- The Des Moines Register. Ad for Varsity Theater. Page 10. June 26, 1992

Leave a comment