Burlesque at the Iowa State Fair wasn’t just a novelty—it was a tradition woven into the fabric of the midway. While newspapers didn’t chronicle it every year, the girlie shows were a familiar draw for decades, offering a mix of comedy, dance, and risqué glamour. These performances thrived in the shadows of Ferris wheels and food stands, quietly shaping fair culture even as public debates about morality and entertainment flared only when controversy made headlines.

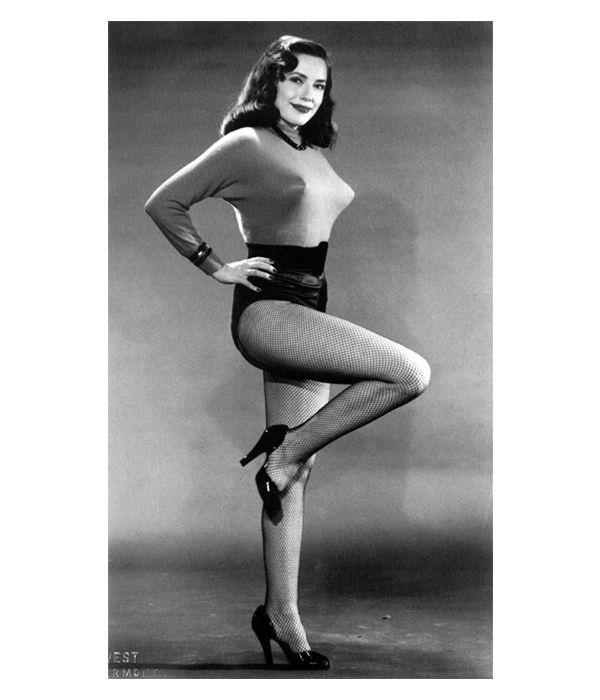

The Queen of the Midway: Evelyn West | 1951

At the heart of the Iowa State Fair in August 1951, a burlesque performer named Evelyn West ignited a cultural firestorm—and reaped the rewards. Known as “the girl with the $50,000 treasure chest,” West was no stranger to spectacle. But when her girlie-girlie show drew criticism from political figures, it became more than entertainment—it became a flashpoint for debates about morality, publicity, and the power of performance.

The Spark: Political Pushback

Iowa Democratic Chairman Jake More denounced West’s show for displaying “nudity” and “lewdness,” prompting West to respond with characteristic flair. She defended the revue as clean, professional entertainment, popular among farmers and their wives. “Anyone who sees anything like that in a good clean ‘girlie show’ would get the same reaction out of watching a pretty girl walk down the street,” she quipped.

The Surge: Publicity Pays Off

The controversy didn’t dampen interest—it doubled it. West’s show reportedly earned $8,000 in a single day (about $37,000 today), and her insured bosom became a headline-grabbing asset. Even as former President Herbert Hoover prepared to speak nearby, crowds flocked to West’s performance. Hollywood cowboy Lash La Rue lamented the attention she received, claiming it overshadowed his own act and compromised the fair’s spirit.

The Takeaway: Power, Performance, and Public Perception

Evelyn West’s savvy use of controversy not only amplified her fame but also challenged prevailing norms about morality and entertainment. In a world where spectacle often drives attention, West’s experience reminds us that the boundaries of “clean” fun are contested and shaped by those who control the narrative. Her legacy prompts ongoing questions about who holds the power to define cultural values and how performers navigate those shifting landscapes.

Educational TV Meets the Midway | 1970-1971

Two decades later, burlesque was still stirring debate—this time in the realm of public broadcasting. Iowa State Treasurer Maurice Barringer criticized the Iowa Educational Broadcasting Network for including footage of a “girlie show” in a fair segment filmed by state educational television crews. The question wasn’t just about entertainment—it was about whether such imagery belonged in classrooms. The controversy underscored how burlesque, once a fairground staple, was increasingly viewed as incompatible with educational values.

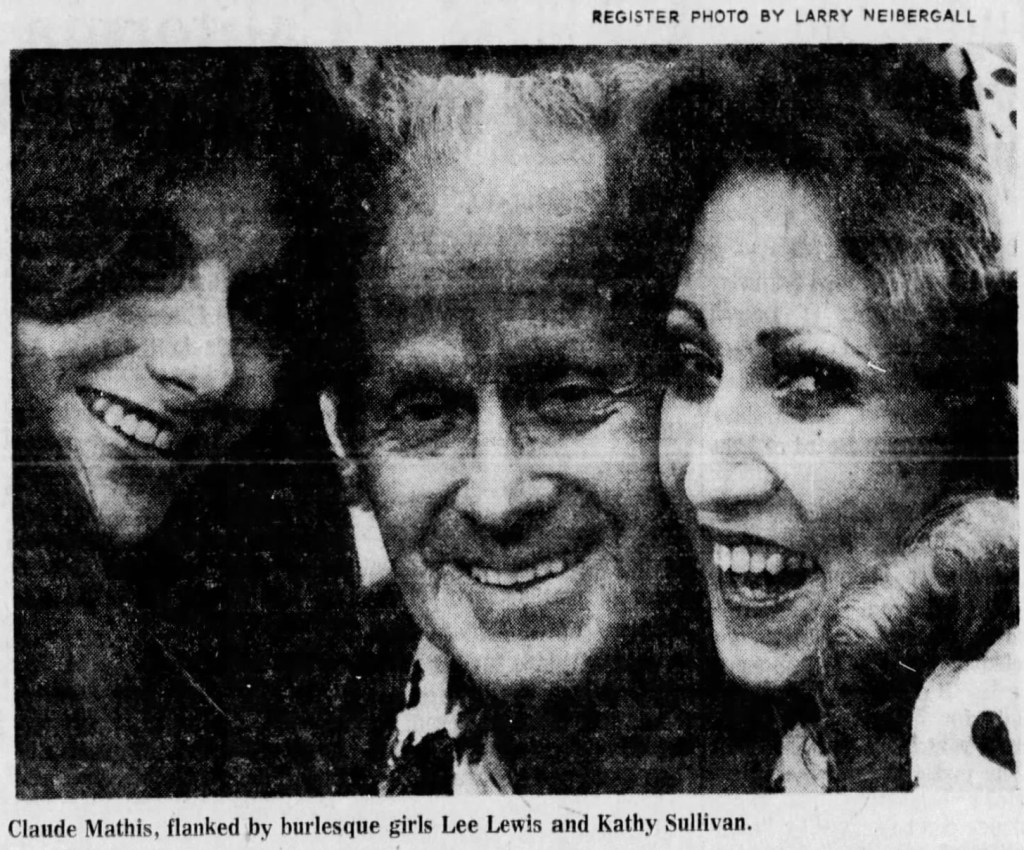

The Last Curtain Call | 1975-1978

By the mid-1970s, burlesque at the Iowa State Fair was fading. In 1975, Dave Hanson’s classic burlesque show featured 75-year-old comedian Claude Mathis and fan dancer Sandy O’Hara—a nostalgic nod to an earlier era. But the following year, the show was canceled. Al Kunz, owner of Century 21 Shows, blamed changing times:

“It’s a permissive society. Girls started wearing tight hot pants, X-rated movies started, and you can see almost anything on television now.”

When burlesque returned in 1978 under Ted Hawkins, it was a toned-down version: dancers stripped only to pasties and G-string thongs. A midway worker summed up the business logic:

“We’ve been here for 19 years and had the girls here for all but two. And now with the girls back, we get the men over there, who get hot from watching the girls and need to come to see us for a cold drink.”

Burlesque & the Midwestern Imagination

From Evelyn West’s headline-grabbing act to the nostalgic revues of the 1970s, burlesque at the Iowa State Fair mirrored broader cultural shifts. What began as a thrilling spectacle became a contested tradition, squeezed out by changing tastes and new media. Yet its legacy endures—as a reminder that entertainment is never just about fun; it’s about who gets to define what’s acceptable, and why.

Sources

- Evening World Herald. “Midway Queen Says Iowans Like ‘Girlie Show.” August 29, 1951

- Lincoln Journal Star. “Publicity Increases Business For Girl Show at Iowa Fair.” Des Moines, IA. August 30, 1951

- Omaha World Herald. “Iowa Official Gives ‘X’ to an ETV Film.” Des Moines, IA. Page 4. August 29, 1972

- The Daily Nonpareil. “Burlesque Player Rues Nudity Trend.” Des Moines, IA. Page 2. August 24, 1975

- The Daily Nonpareil. “Entrepreneur Fights to Save Burlesque.” Des Moines, IA. Charles Roberts. Page 3. September 9, 1975

- The Des Moines Register. “Old-time burlesque show planned for state fair.” Dix Hollobaugh. Page 25. July 27, 1975

- The Des Moines Register. “Burlesque going the way of all flesh.” Patrick Lackey. Page 9. August 17, 1975

- Lincoln Journal Star. “You Can Barely See the Cuties Anymore.” Des Moines, IA. Page 1. August 20, 1976

- Omaha World Herald. “Girlie Show Returns to Fair.” Des Moines, IA. Page 29. August 18, 1978

- The Lincoln Star. “Fair to offer ‘girlie’ show.” August 21, 1978

Leave a comment