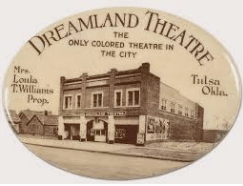

The Dreamland Theatre stood at the heart of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, a community built through Black entrepreneurship, mutual support, and cultural ambition. When John and Loula Williams opened the theatre in 1914, they created far more than a movie house—they built a gathering place where Black audiences could experience live performance, political organizing, and the everyday pleasure of entertainment in a segregated city. Dreamland’s stage hosted traveling companies, local musicians, lecturers, boxing matches, and community meetings, reflecting the breadth of Black performance culture in the early twentieth century. Its history, from its celebrated opening to its destruction in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and its later rebirth, mirrors the resilience and vulnerability of Greenwood itself.

*Trigger warning: This article will discuss the Tulsa Race Massacre

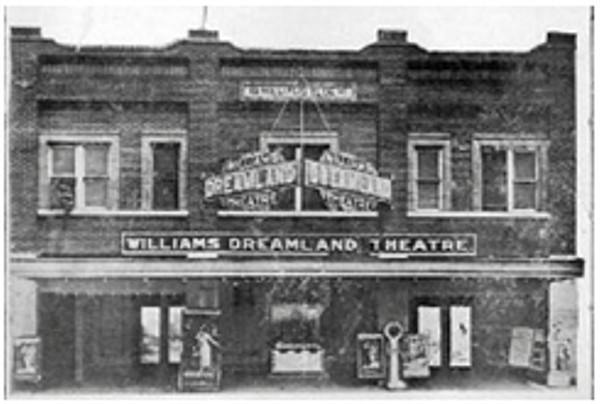

The Williams Dreamland Theatre | Greenwood District

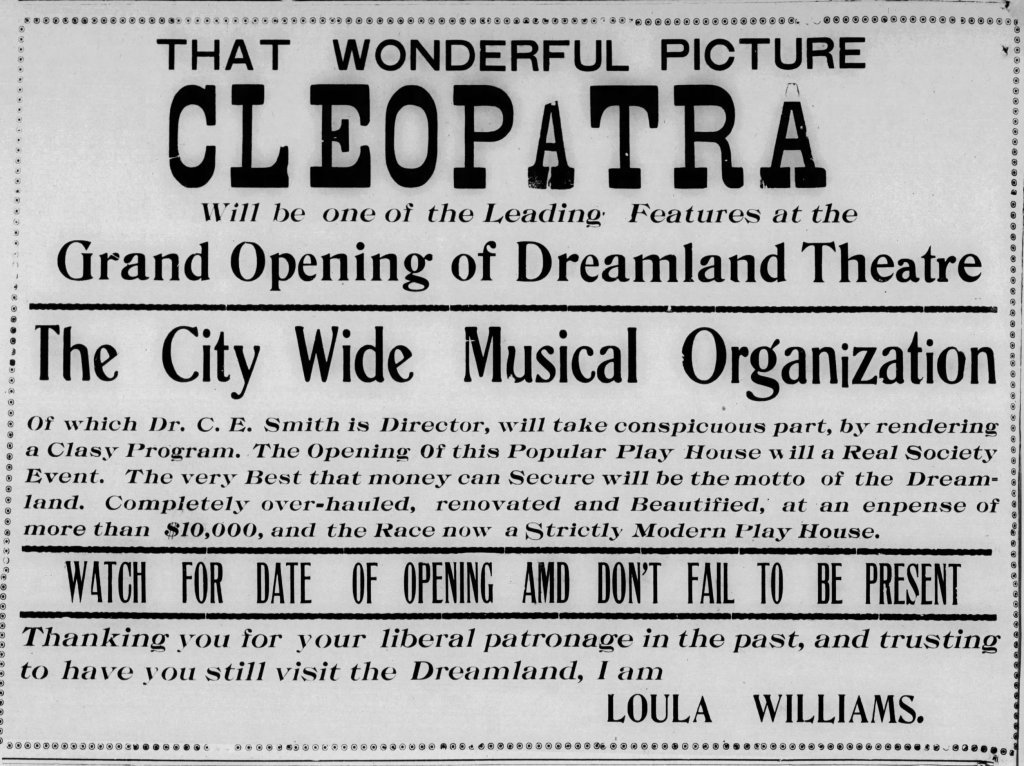

John and Loula Williams opened their Dreamland Theatre on August 30, 1914, building it beside the Williams Confectionery (which had been operating on the site since 1909). Although it was the second venue to carry the Dreamland name, the earlier one was an unrelated nickelodeon located in downtown Tulsa. The Williams invested $10,000 into the new theater, adding it to their growing portfolio, which already included the confectionery and a well‑known auto repair business.

The success of the Tulsa Dreamland led the couple to establish two additional Dreamland theaters in Oklahoma — one in Muskogee and another in Okmulgee. Its final performances took place the night before the Tulsa Race Massacre, on May 31, 1921.

Performances at the Dreamland

Although surviving advertisements rarely use the term “burlesque,” Dreamland’s early programming places it firmly within the same entertainment traditions that shaped Black vaudeville and revue‑style performance in the 1910s and 1920s. Touring companies such as the Georgia Smart Set, stock companies like Bruce & Bruce, and mixed‑bill evenings featuring music, comedy, specialty acts, and “cabaret” numbers were all part of the broader ecosystem that produced early Black burlesque performers. These shows blended humor, dance, flirtation, and musical virtuosity in formats nearly identical to the traveling revues and “smart set” companies that circulated through the Midwest and Southern states.

An inconclusive list of performances at the Dreamland Theatre, pre-1921:

- The White Sisters (September 1914)

- W.A. Eiler’s New Orleans Minstrels (October 7, 1914)

- “The Million Dollar Mystery” (October 1914)

- Lecture by Rev. Chas. Stewart of Chicago (November 1914)

- Lecture by Hon. Harrison of Oklahoma City (November 1914)

- The Man of Mystery or “NEMO” or The Jail Breaker (November 1914)

- Local businesses rendered a weekly program of music and oration (November & December 1914)

- Local Business League held meetings and speakers on stage (1914-1916)

- Hon. J. Milton Turper before local Business League spoke at Dreamland (January 1915)

- Photo play “Life of Samson” (June 1915)

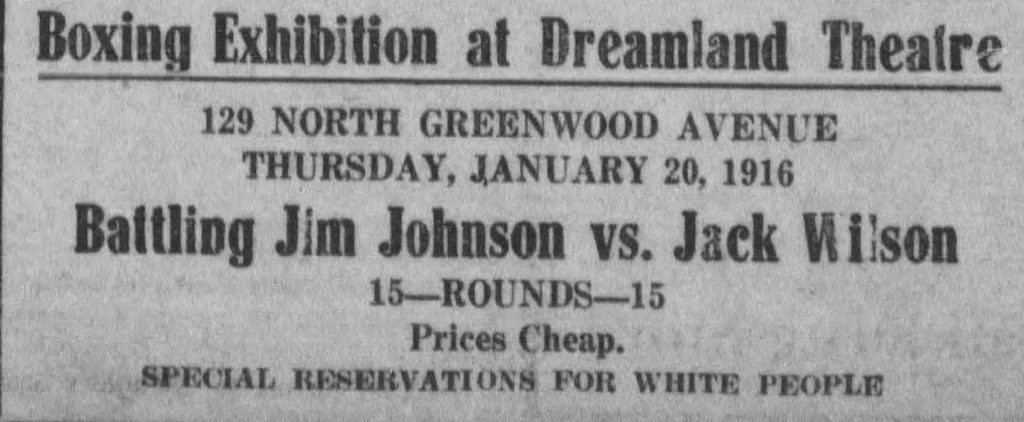

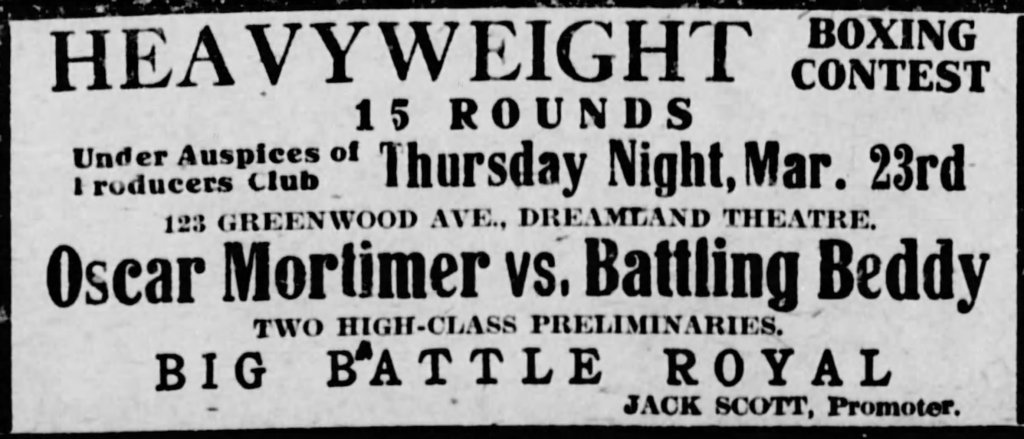

- Boxing match between Jim Johnson and Jack Wilson (January 20, 1916)

- Boxing match between Harry Lindsay and Harry Wallace (January 1916)

- Boxing match between Harry Lindsey and Scotty Williams (March 1916)

- Dogs and monkey act (June 1916)

- L.B. McCoy’s Blues titled “The Georgia Barrel House Blues” (June 1916)

- Boxing match between Harry Lindsay of St. Joseph, MO and Geo. Christian of Columbus, OH (June 1916)

- “The Secret Submarine” 3 episodes photo play(July 1916)

- “The Georgia Smart Set: A Colored Show That’s Different” (July 1916)

- Boxing matches are a regular occurrence at the Dreamland (Summer 1916)

- Mass meeting of 600 Black voters to protest enforcement of the segregation ordinance (August 7, 1916)

- The Bruce & Bruce Stock Company (September 1916)

- Boxing match between Oscar Mortimer and Battling Beddy (March 1917)

- Miss Grozia Corneal, violinist (February 1918)

- Hazel B. McDaniel presented a drama “Dot’s Conversation” with the pupils of the Booker Washington High School of Sapulpa (February 1918)

- The Old Maids’ Convention (March 19, 1918)

- “Cleopatra” and the City Wide Musical Organization (September 1918)

- “The Unbeliever” moving picture (October 9 & 10, 1918)

- Speech by Judge E.I. Saddler on “Race achievements” (November 1918)

- “The Eyes of the World” moving picture (November 23, 1918)

- The “Unknown” Company with Mademoiselle LaRue Shoecraft (December 1918)

- The Tulsa Choral Club performed a musical (December 17, 1918)

- Dr. C.E. Smith (physician) rendered a music program at the Dreamland (December 1918)

- Bill McLain hosts a “Cake Walk” with a cabaret floor show (December 1918)

- Madam Anita Brown “The Queen of Song”, accompanied by Clearance Thomas White and T. Theodore Taylor (February 1919)

- “The Iron Test” photoplay (February 15, 1919)

- Boxing match between Sam Langford and Jack Thompson (July 1919)

- The Doc Straine Company (February 1920)

- Robert Conness in the “Witching Hour” (February 28, 1920)

A 1915 article states the Dreamland Theatre was giving away “prizes” to the audience in the form of groceries and other “provisions.” A mass meeting was held the same year to organize leaders and laymen “of the Race” for “mutual protection.”

Dreamland’s role as a community hub for variety entertainment — from minstrel troupes to cakewalks to late‑night rambles — situates it squarely within the performance lineage that later fed mid‑century burlesque, shake dancing, and nightclub revue culture in Black entertainment districts across the country.

The Greenwood District & the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

In the early 20th century, Tulsa’s Greenwood District—known nationally as “Black Wall Street”—was one of the most prosperous Black communities in the United States. The neighborhood thrived with Black‑owned businesses, professional offices, restaurants, hotels, and entertainment venues like the Dreamland Theatre. Its success was the result of deliberate Black investment and community building, especially after educator and entrepreneur O.W. Gurley purchased land for Black residents to develop their own economic center.

That prosperity made Greenwood a target. On May 31, 1921, after a disputed encounter between a Black teenager, Dick Rowland, and a white elevator operator, white mobs mobilized.

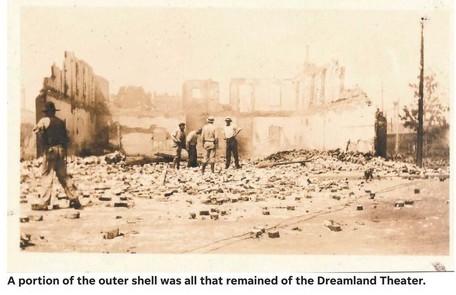

Over roughly 24 hours, armed groups looted and burned 35 blocks of the district, destroying homes, businesses, churches, and cultural institutions. Airplanes were seen overhead as fires spread, and historians estimate that as many as 300 Black residents were killed. Nearly 10,000 people were left homeless.

When violence erupted during the Tulsa Race Massacre the theatre became one of the key gathering points where residents met amid the turmoil to coordinate their response. The building did not survive the destruction that followed. The nearby Dixie Theatre was also lost.

Rebuilding either venue was considered remarkable given the obstacles that followed: city officials, local business interests, and insurance companies all made it extremely difficult for Greenwood’s business district to recover. Their resistance reflected both Tulsa’s entrenched racism and a failed effort by railroad interests to displace Black residents in order to expand rail lines.

Performances after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre:

- Dorothy Gish in “Nell Gwyn” (September 1926)

- Gloria Swanson in “The Untamed Lady” (September 1926)

- “The Wanderer” with Ernest Torrence and Gretta Nissen (September 1926)

- “Sea Horses” with Jack Holt and Florence Vidor (September 1926)

- “Crown of Lies” with Pola Negri (September 1926)

- “The Secret Spring” (September 1926)

- Thomas Mcighan in “the New Klondike” (September 1926)

- “The Trail of ’98” – 25% of admissions to YWCA (March 1929)

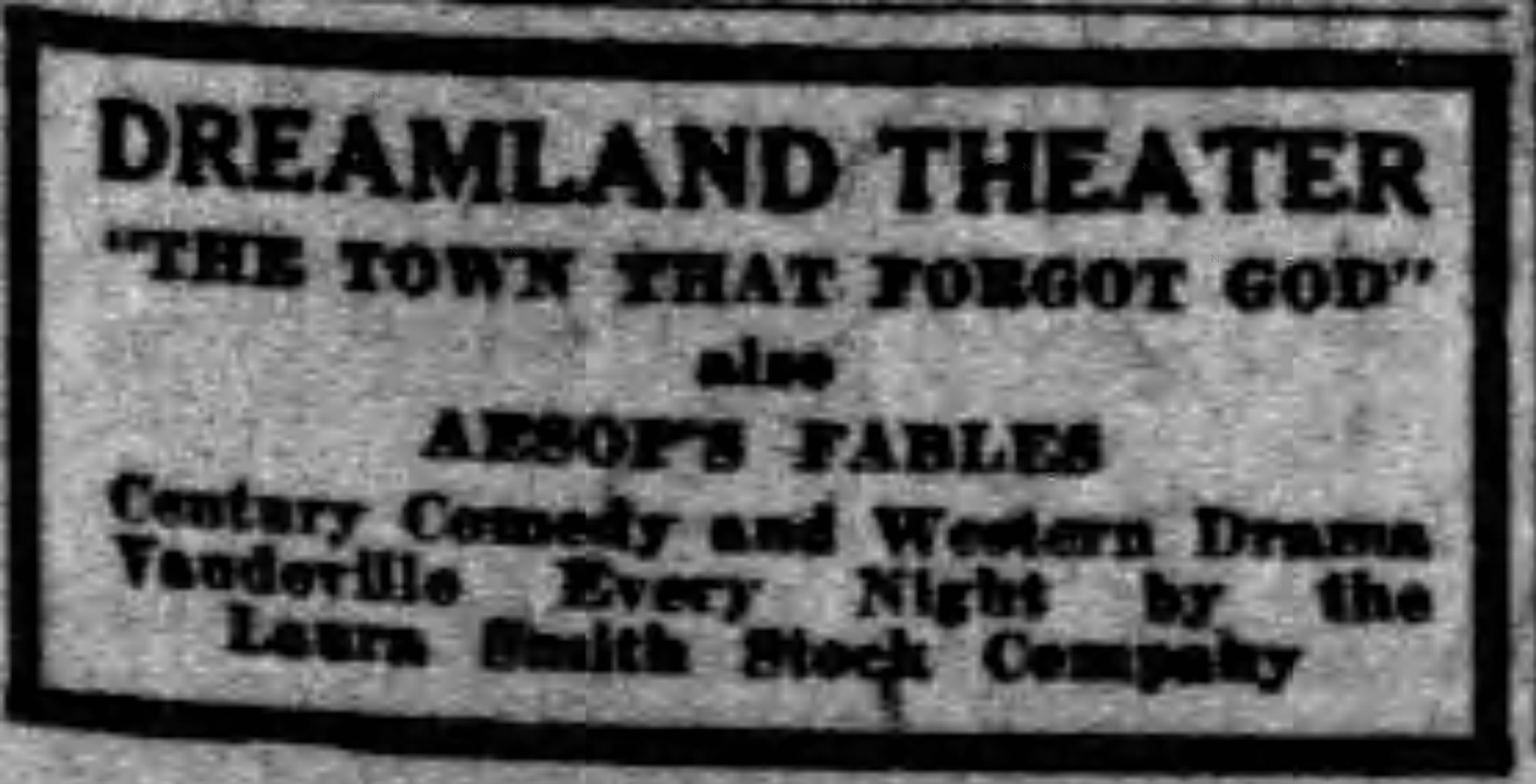

- Hoot Gibson in “Dead Game” and Laura Smith Stock Company every night (September 1923)

- Corrine Griffith in “A Woman’s Sacrifice” and Laura Smith Stock Company every night (September 1923)

- William Duncan in “Steel Trail” and Laura Smith Stock Company every night (September 1923)

- “The Town that Forgot God” and Aesop’s Fables and Laura Smith Stock Company every night (September 1923)

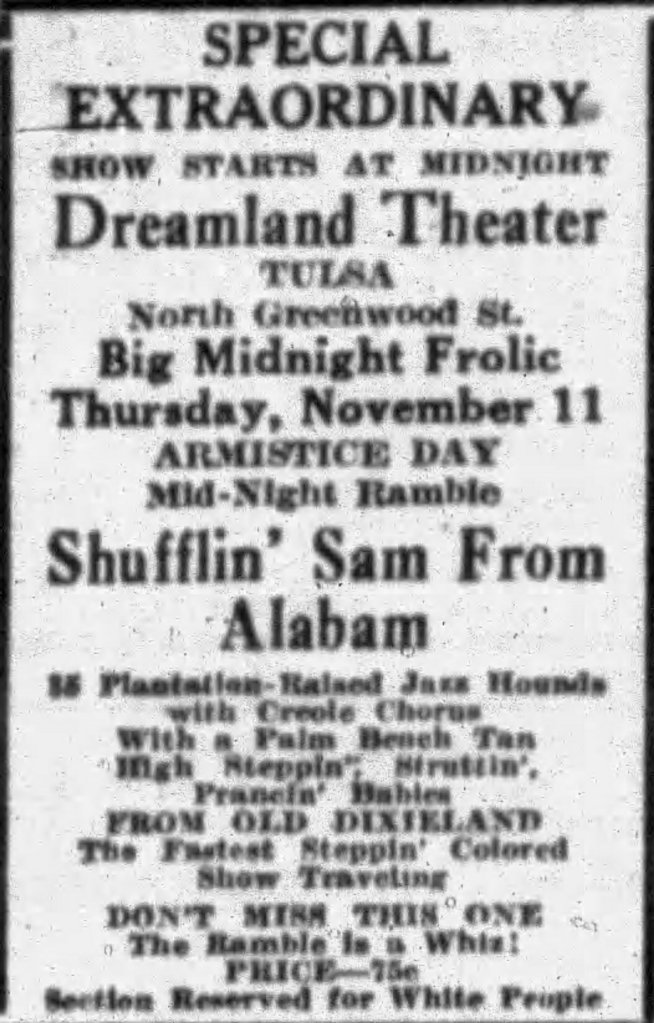

- Midnight Frolic/Ramble featuring “Shufflin’ Sam From Alabam” (November 1926)

- “The Fleet’s In” featuring Clara Bow, benefitting the Archer Street Y.W.C.A., the Negro Girls Reserve, and the Negro Baby Clinic (June 1929)

The pressure nearly succeeded in stopping the Williams family from rebuilding. Their Muskogee Dreamland Theatre fell into receivership in April 1922, and the couple faced a series of unsuccessful lawsuits while trying to construct a new Greenwood theatre. Even so, the replacement Dreamland opened in September 1922—barely a year after the massacre—and included a small hotel on its second floor.

By the mid‑1920s, however, the Williams’ financial stability had eroded, and Loula Williams’ health was declining. The family sold the Dreamland Theatre in 1927, and Loula died soon afterward; contemporary accounts suggested that the strain of rebuilding contributed to her decline. Under new ownership, Dreamland and the former Royal Garden Theatre (later the Rex Theatre) became long‑running, white‑owned movie houses that continued to serve Black audiences.

To stay competitive, Bijou Entertainment converted Dreamland to sound films. Over the years, the theatre faced new rivals from Black-owned venues, including the Regal Theatre (1944–1949), the New Regal/Ace Theatre (opened 1951), and the Peoria Theatre (opened 1947).

Bijou closed Dreamland on February 17, 1952, after screenings of Breakthrough and Under Mexicali Stars. The building sat vacant for three years before returning to Black ownership as a live-events venue under several names: Dreamland Hall, Dreamland Emporium, and Dreamland Arena. In 1957, it was rebranded as the Dreamland Playhouse, hosting stage productions and special events until around 1963.

By the mid‑1960s, Greenwood was in steep economic decline, and vacancies were widespread. This time, the city didn’t need to burn Dreamland down—it simply auctioned the building on April 5, 1967 and later demolished it as part of urban renewal. The back of the former Dreamland site now sits against Interstate 244, a highway intentionally routed through Greenwood in a way that maximized disruption and noise.

Even without its physical structure, Dreamland’s legacy endured. It resurfaced in cultural memory through projects like the 2021 HBO documentary Dreamland: The Burning of Black Wall Street and through Dreamland Tulsa, an arts space established near the theatre’s former location in the 2020s.

Reflecting Back…

In tracing the life of the Williams Dreamland Theatre, we see how deeply performance shaped Greenwood’s social world. The theatre’s mixed bills, traveling companies, cabaret evenings, and community gatherings reveal a vibrant entertainment culture that connected Tulsa to broader Black performance networks across the Midwest and South. Though Dreamland was repeatedly threatened—first by racial violence, later by economic decline and urban renewal—its legacy persists in the artists it hosted, the audiences it served, and the cultural traditions it helped sustain.

Sources

Websites:

- Williams Dreamland Theatre in Tulsa, OK – Cinema Treasures

- Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, Explained | Teen Vogue

- Dreamland Theatre in Tulsa, OK – Cinema Treasures

- New Dreamland Theater in Tulsa, OK – Cinema Treasures

- Pease, Josie, I, and Lisa Spikes, Bevan Houston and Natoya Marston. “Williams Dreamland Theatre.” Clio: Your Guide to History. November 9, 2022. Accessed January 2, 2026. https://theclio.com/entry/137393

Newspaper Articles:

- The Tulsa Evening Sun. “Coloreds Were Drunk.” Page 3. November 27, 1914

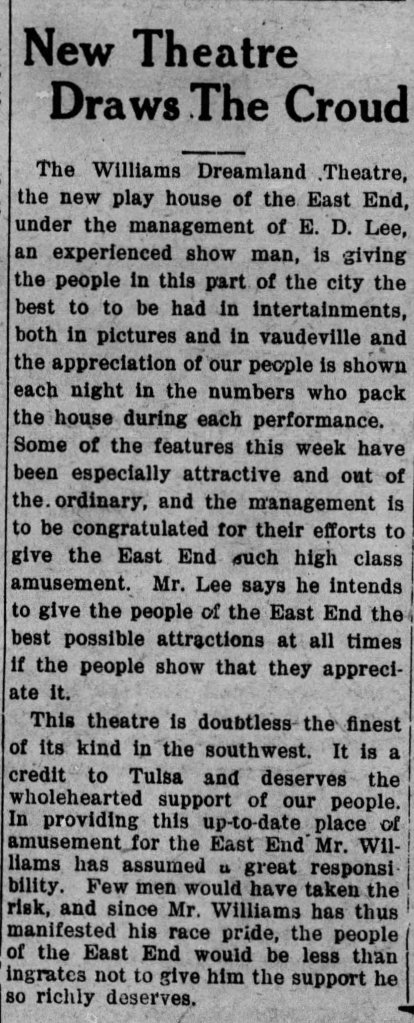

- The Tulsa Star. “New Theatre Draws the Croud.” Page 4. September 5, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. The White Sisters. Page 5. September 26, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. The New Orleans Minstrels. Page 4. October 3, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “The Million Dollar Mystery”. Page 5. October 3, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “Chicagoan Lectures Men and Women.” Page 1. November 7, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “A grand rousing”. Page 8. November 7, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “Man of Mystery at The Dreamland.” Page 1. November 21, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “Local League to Render Program Sunday P.M.” Page 1. November 28, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “Lawyer Harrison to Address Tulsa League Sunday.” Page 1. December 19, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. “Business League Hears J. Milton Turner Speak.” Page 1. January 16, 1915

- The Tulsa Star. Page 5. June 5, 1915

- The Tulsa Star. The Dreamland Theatre. Page 4. June 19, 1915

- The Tulsa Star. “State-Wide Mass Meeting; Called to Meet in This City.” Page 1. September 3, 1915

- The Tulsa Star. Page 8. December 4, 1915

- The Tulsa Star. “Theatrical News.” Page 5. June 12, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. “The Star.” Page 4. June 27, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. “Sporting News: Boxing.” Page 5. June 27, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. The Secret Submarine. Page 5. July 4, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. “The Bruce & Bruce Stock Company.” Page 5. September 23, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. “Violin Viruoso Ends Tulsa Engagement.” Page 6. September 7, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “Sapulpa Pupils Appeared in Drama Here.” Page 1. February 16, 1918

- Tulsa World. “Colored Heavies To Box Tomorrow.” Page 6. January 26, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. “The Old Maids’ Convention.” Page 4. March 9, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “Popular Play House; Will Have Its Grand Opening Within the Next Few Days.” Page 6. September 7, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. Mrs. Loula Williams. Page 3. September 28, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. Page 3-4. November 9, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “The Eyes of the World.” Page 2. November 23, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “The Unknown Company.” Page 2. December 7, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “Musical.” Page 1. December 14, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. Page 10. December 21, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. “Madam Anita Brown Captivates Tulsaites; The Queen of Song, Lives up to Her Great Name as a Singer.” Page 1. February 1, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. Page 2. February 1, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. “The Iron Test.” Page 1. February 15, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. Page 3. February 7, 1920

- The Tulsa Star. “The Doc Straine Company.” Page 7. February 14, 1920

- The Tulsa Star. “Robert Conness.” Page 7. February 28, 1920

- The Tulsa Star. “Republicans Form State Organization.” Page 1. October 9, 1920

- The Tulsa Tribune. “Fans Watch Big Negro heavy of Tulsa Exercise.” Page 6. August 19, 1916

- The Tulsa Tribune. “Negroes Will Hold A Cake Walk Rally.” Page 8. December 8, 1918

- Tulsa Daily Legal News. “Bill of Sale.” Page 2. March 26, 1915

- Tulsa World. “Dark-Skinned Inhabitants of ‘Little Africa’ Doing Well in the Light of White Metropolitan Improvements.” Page 15 & 27. July 4, 1915

- Tulsa World. “Important Bout Is Scheduled Tonight.” Page 6. March 2, 1916

- Tulsa World. “‘Tham’ Langford to Arrive Here Today.” Page 10. July 31, 1919

- Tulsa World. “Negro Held For Murder.” Page 2. September 6, 1920

- The Tulsa Tribune. “Old Showman Leases Two Tulsa Theaters.” Page 4. April 9, 1926

- The Tulsa Tribune. “For Negro Benefits.” Page 2. June 20, 1929

- The Tulsa Tribune. “Man Bound in Theater Theft.” Page 1. September 24, 1937

- The Tulsa Tribune. “Dozen a Day.” Page 34. August 7, 1956

- Tulsa World. “2 Tulsa Theaters Leased by Cotter.” Page 9. April 9, 1926

- Tulsa World. “Assist Negro Y.W.C.A.” Page 6. June 21, 1929

- Tulsa World. “Negro Fatally Stabbed.” Page 4. March 23, 1931

- Tulsa World. “Theater Faces Suit Following Attack.” Page 14. October 21, 1934

- Tulsa World. “Movie Reel Burns.” Page 5. December 29, 1935

- Tulsa World. “Robbery.” Page 11. September 25, 1937

- Tulsa World. “Mayor’s Party.” Page 1. December 21, 1937

- Tulsa World. “Emancipation Day Picnic Draws 3,000.” Page 12. June 20, 1940

- Tulsa World. “Tin Can Matinee is Huge Success.” Page 3. May 18, 1941

- Tulsa World. “Another ‘Tin-Can’ Matinee Planned.” Page 2. May 23, 1941

- Tulsa World. “Not Fair” Page 41. May 14, 1953

Newspaper Advertisements:

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for the W.A. Eiler’s New Orleans Minstrels. Page 8. October 3, 1914

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for The Georgia Smart Set. Page 5. July 4, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for Bruce & Bruce. Page 5. September 23, 1916

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for Cleopatra. Page 8. September 7, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for Fresh Salted Peanuts at the Dreamland Theatre. Page 3. December 21, 1918

- The Tulsa Star. Ad for the Red Wing Hotel above the Dreamland Theatre. Page 7. February 14, 1920

- The Tulsa Tribune. Ad for Boxing Match between Jim Johnson and Jack Wilson. Page 6. January 18, 1916

- The Tulsa Tribune. Ad for Paramount Week. Page 23. September 5, 1926

- The Tulsa Tribune. Ad for The Trail of ’98. Page 15. March 13, 1929

- Tulsa World. Ad for Hoot Gibson in “Dead Game”. Page 5. September 5, 1923

- Tulsa World. Ad for Corrine Griffith in “A Woman’s Sacrifice.” Page 13. September 6, 1923

- Tulsa World. Ad for William Duncan in “Steel Trail.” Page 3. September 7, 1923

- Tulsa World. Ad for “The Town that Forgot God” and Aesop’s Fables. Page 7. September 8, 1923

- Tulsa World. Ad for Bid Midnight Frolic on November 11. Page 18. September 3, 1930

- Tulsa World. Wanted Ad for Colored Chorus Girls. Page 18. September 3, 1930

Dreamland Theaters #2 and #3 Articles:

- The Tulsa Star. “Dreamland Theatre Number 2; Will be Opened in Muskogee January 15.” Page 3. January 4, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. The Johnson-Fisher Stock Company. Page 4. January 4, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. Dreamland No. 2 and 3. Page 4. February 1, 1919

- The Tulsa Star. The DeLuxe Company at Dreamland No. 3. Page 3. February 7, 1920

Leave a comment