In the spring of 1986, a bachelor party at a rural tavern outside Des Moines unexpectedly became the center of a statewide political firestorm. What should have been remembered as a night of beer & laughter, instead ignited one of Iowa’s most talked‑about morality scandals of the decade. The incident — quickly dubbed the “nude dance scandal” in headlines — exposed not only the behavior of a state legislator, but the deep tensions simmering beneath Iowa’s debates over sexuality, public decency, and the policing of erotic labor.

The Incident in Mingo, Iowa

On April 17, 1986, a group of lawmakers and lobbyists boarded a rented bus at the Iowa Capitol and headed to the Back Forty Tavern in Mingo, a small town northeast of Des Moines. The occasion: a bachelor party for State Representative Ed Parker, a Democrat from Mingo, who was set to marry on May 10.

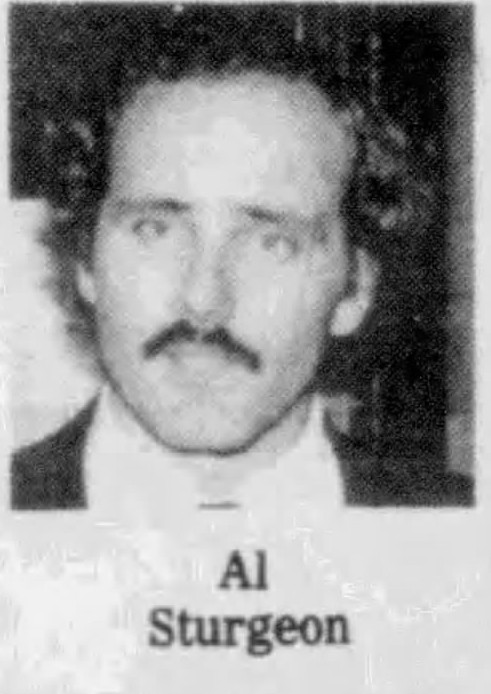

About 25 legislators attended — mostly Democrats, with one Republican — and the evening reportedly included two nude dancers, hired by lobbyist F. Richard Thornton, who later publicly apologized. According to witnesses, State Representative Al Sturgeon engaged in a sex act with one of the dancers, Dawn Wilson, during her performance. Both were later indicted for indecent exposure.

The party quickly unraveled. Rep. Roger Halvorson, a Monona Republican, said he left “when the dancing began.” House Speaker Donald Avenson also departed early, later calling the event “very embarrassing, improper, disgraceful action.” Parker claimed he was in the kitchen talking to Avenson and left shortly after singing an Irish song. “I don’t know what happened in the other room,” he told reporters. (The Des Moines Register. April 20, 1986)

Statewide Scandal

The story exploded in the newspapers from Council Bluffs to the Quad Cities, as it touched several cultural nerves at once. At the time, Iowa lawmakers were actively debating restrictions on nude dancing, liquor‑license rules, and “community standards” around obscenity. The mid‑1980s were a peak moment for anti‑obscenity campaigns, conservative “decency” movements, and heightened scrutiny of adult bookstores, strip clubs, and taverns.

Patrick Cavanaugh, director of the Iowa Beer and Liquor Control Department, confirmed that nude dancing at a tavern was illegal, and the incident triggered calls for tighter enforcement statewide. The 1986 scandal prefigured later conflicts involving Big Earl’s Goldmine, Tuxedos, and the Davenport and Quad Cities’ enforcement patterns. These cases reveal a long, consistent pattern: Iowa’s discomfort with erotic labor often manifests through legal pressure, zoning restrictions, and public shaming.

Legal Fallout

The legal consequences were swift and highly publicized. Jasper County prosecutors charged five individuals: Rep. Al Sturgeon and dancer Dawn Wilson for indecent exposure, tavern owner Larry “Bud” McKinney for permitting the act, lobbyist F. Richard Thornton for violating Iowa’s gift law, and Wilson’s booking agent for aiding the performance. While Thornton’s gift-law violation highlighted the murky ethics of lobbyist influence, the indecent exposure charges became the scandal’s centerpiece.

Wilson initially pleaded innocent but later entered a guilty plea “without specific admission,” receiving a one-year suspended sentence. Sturgeon’s case dragged on for months, fueling speculation about political fallout, though he ultimately avoided jail time. The incident exposed gaps in Iowa’s liquor and entertainment statutes, prompting calls for stricter enforcement and legislative reform.

The Dancers

Dawn Wilson, the dancer charged alongside Sturgeon, became a lightning rod for cultural anxieties. In the press, she was rarely portrayed as a working professional; instead, she was cast as a moral archetype—a temptress corrupting public servants, a fallen woman deserving punishment, or a cautionary tale for “small-town values.” Dawn testified the dancers were paid $120 each plus gas money.

This framing reflected a broader pattern in 1980s media: erotic labor was sensationalized, stripped of economic context, and recoded as a threat to civic virtue. Wilson’s own voice was almost entirely absent from coverage, replaced by speculation and innuendo that reinforced gendered stereotypes.

The second dancer, Karee Anderson, occupied a different but equally constrained role in the narrative. Her testimony before the grand jury was treated as salacious detail rather than evidence of ambiguity. Anderson stated that Wilson later admitted to the act in question, though she did not witness it herself. She and her boyfriend saw the end of Wilson’s performance and noticed nothing unusual—an observation that complicated the scandal’s most lurid claims but received little attention.

Both women were reduced to caricatures in a story that was less about their lives and more about the political theater surrounding them. Anderson was from Fort Dodge; Wilson, from Des Moines—two ordinary Iowans swept into an extraordinary storm.

Media Frenzy & Public Reaction

The press seized on the story with gusto. Headlines like “Bachelor Bash Turns Political Blunder” and “Legislators in Nude Dance Uproar” dominated front pages, framing the event as a morality crisis. Editorials thundered about “decency” and “public trust,” while talk radio and letters to the editor reflected a divided public—some demanded resignations, others dismissed the scandal as prudish overreach.

Rural voices often defended the tavern as a local watering hole, while urban commentators linked the incident to broader debates over obscenity and community standards. Lost in the uproar were the dancers themselves, whose work was sensationalized and stripped of context, reinforcing stereotypes rather than exploring the realities of erotic labor.

Legacy and Culture Impact

The Mingo scandal reverberated far beyond 1986. It foreshadowed Iowa’s escalating battles over adult entertainment, culminating in the 1997 statewide ban on nude dancing in liquor-licensed establishments. Later controversies—from Big Earl’s Goldmine in Des Moines to Tuxedos in Davenport—echoed the same themes: moral panic, zoning crackdowns, and the persistent framing of erotic performance as a threat to public order.

The 1986 case also underscored how gender and power intersect in political scandals: legislators largely escaped lasting consequences, while dancers bore legal and cultural punishment. Today, the bachelor party in Mingo stands as a vivid reminder that debates over sexuality and “decency” often reveal more about political theater than about the people whose labor is at stake.

Sources

- Ronald G. Farkas, Doing Business As Tuxedos;

- State senator pleads guilty to reduced charge – UPI Archives

- https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/02/11/State-senator-pleads-guilty-to-reduced-charge/4540540018000/

Newspaper Articles:

- The Daily Nonpareil. “Two legislators, three others cited for bachelor bash.” Newton (AP). Page 1. August 19, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. “Stag party for legislator at bar ‘got out of hand’.” Page 1A, 5A. April 20, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. “Avenson deplores ‘disgraceful action’ at lawmakers’ party.” Bob Shaw. Page 1A, 2A. April 22, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. “James P. Gannon.” Gannon. Page 1C, 2C. April 27, 1986

- The Des Moines Register. “Grand jury to investigate Mingo Party.” Blair Kamin and Ken Fuson. May 16, 1986

- The Dispatch. “Iowans unimpressed by ‘Mingo-gate’.” Des Moines, IA. Page 21. June 9, 1986

- The Dispatch. “Lawmakers indicted after party.” Des Moines, IA. Page 1. August 19, 1986

- The Dispatch. “Man of bachelor party fame says turnout shows support.” Mingo, IA. Page 10. August 27, 1986

- The Gazette. “Mingo dancer pleads guilty to exposure.” Associated Press. Page 8. November 18, 1986

- The Gazette. “Iowa gift law stripped away; Judge in Mingo-party case says bill passed improperly.” Newton, IA. Page 2. December 9, 1986

Leave a comment