In the American Midwest of the 1890s and early 1900s, an “opera house” was less a temple to grand opera than a multipurpose engine of local culture—part concert hall, part civic forum, part funhouse of traveling amusements. Moline’s Wagner Opera House fit that profile perfectly.

While not as widely remembered as the larger Moline Opera House that followed later, the Wagner Opera House played a remarkable role in shaping the city’s early performing‑arts scene. Newly surfaced newspaper advertisements and reviews show that, far from being a genteel outpost, the Wagner, at one period, was a burlesque house—a venue that booked headline touring troupes, introduced risqué satire to Quad Cities audiences, and, for a time, drew the largest crowds in its history for a form of entertainment reformers loved to scold.

A Stage Built for the Growing City & the Road

Documentation places the Wagner Opera House as an active venue as early as the 1880s. The space hosted musical performances, theatrical works, community entertainment, and local arts organizations—making it one of the city’s earliest dedicated performance halls.

The earliest of the clippings (November 1898) advertises Stetson’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the melodrama “Darkest Russia”, complete with “sparkling comedy” and “between‑the‑acts” novelties. The bill is not burlesque, but it tells us what the Wagner was optimized to do: host touring companies that arrived by rail with scenery, bands, and a grab‑bag of specialty features. That same touring logic—and the same audience appetite for spectacle and satire—soon carried burlesque through the doors.

By December 1899, the Wagner was promoting a two‑night sequence: the “funny farce‑comedy” His Better Half followed by “VANITY FAIR—A Mélange of the Best Features of High‑Class Burlesque and Vaudeville,” promising a strong chorus and entirely new wardrobes. Read literally, this is a house that knew where the draw was.

In the Midwest of this period, “burlesque” often meant a hybrid of comic parody, musical numbers, “leg shows,” and a nimble chorus line—an Americanized descendant of Lydia Thompson’s touring English burlesques that had swept the country in the late 1860s.

“The largest audience which has witnessed any production at the Wagner”

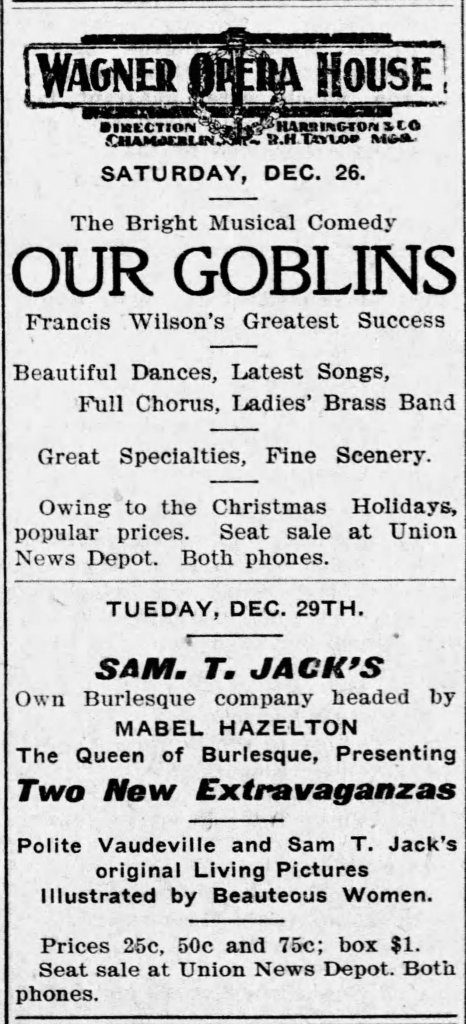

The holiday week of 1903 turns the suggestion into proof. An advertisement for Sam T. Jack’s Own Burlesque Company, headed by Mabel Hazelton—billed right there as “The Queen of Burlesque”—promises “Two New Extravaganzas,” polite vaudeville, and even “Living Pictures illustrated by beauteous women.” The next day, a local review runs under the simple headline “Burlesque Pleases.” It reports the largest audience the house had ever seen and notes, with a wink and no surprise, that it was composed entirely of men.

In a sentence, we can see the whole ecosystem: national burlesque impresarios (Sam T. Jack), star branding (Hazelton as “queen”), mixed‑genre packaging (extravaganza + vaudeville + tableaux), and a gendered audience economy that municipal moralists could deplore but could not deny. It matches what historians observe at the national scale: that burlesque professionalized into circuits and stars even as it flipped social hierarchies onstage, marrying satire to the commercial magnetism of the chorus line.

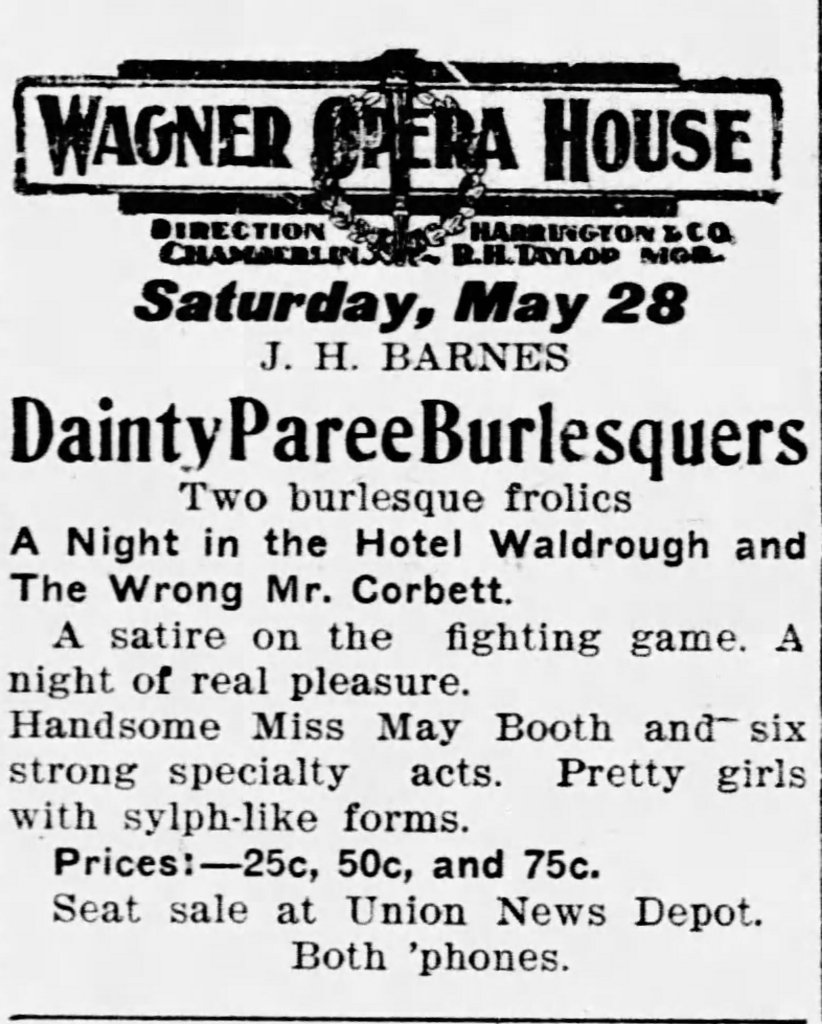

“Dainty Paree” and the Satire of Sport

The Wagner’s spring 1904 ad for the Dainty Paree Burlesquers distills the genre’s tone. The troupe offers “Two burlesque frolics”—A Night in the Hotel Waldrough and The Wrong Mr. Corbett, cheekily billed as “A satire on the fighting game.” (Think James J. Corbett, the first gloved heavyweight champion after John L. Sullivan.) The copy promises Miss May Booth, six strong specialty acts, and “pretty girls with sylph‑like forms.” Burlesque’s mix of topical parody, female‑forward spectacle, and variety discipline is all there in a single column inch.

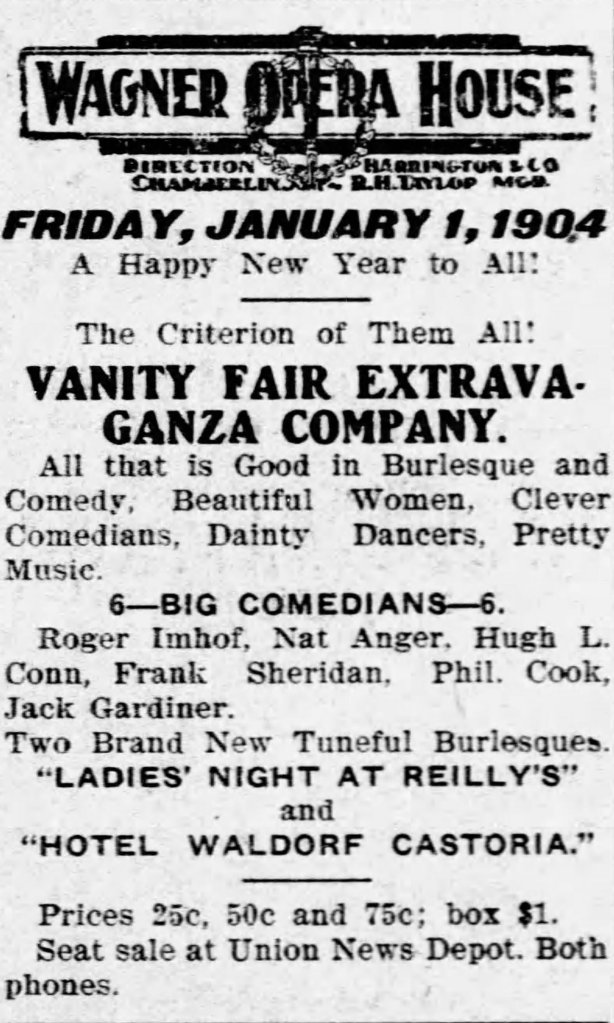

A few months later, New Year’s 1904 opens with another Vanity Fair Extravaganza Company, trumpeting “All that is Good in Burlesque and Comedy” and two tuneful burlesques—Ladies’ Night at Reilly’s and Hotel Waldorf Castoria.

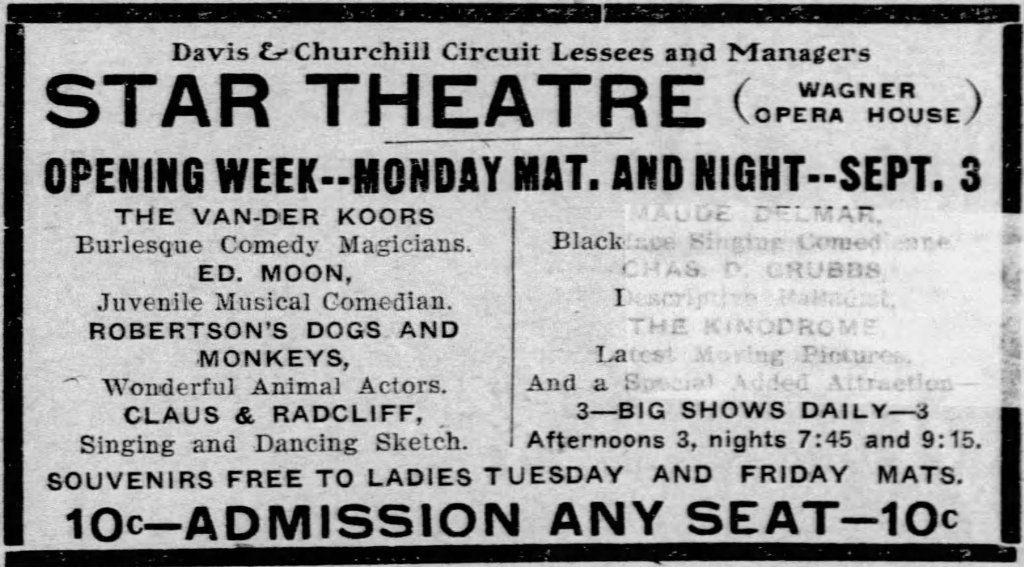

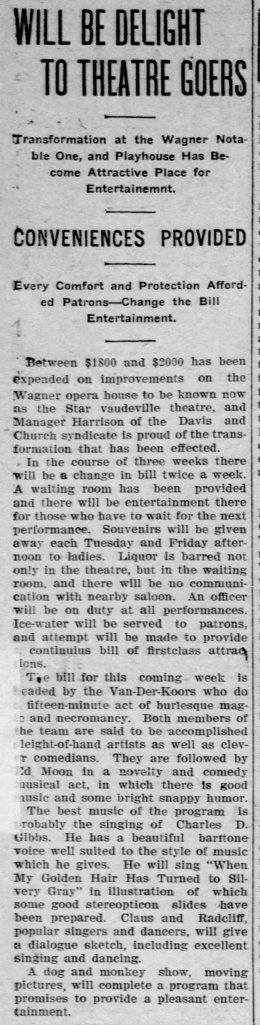

The “Old Wagner” Memory

By September 1906, the Wagner had been remodeled and rebranded as the Star Vaudeville Theatre. The house spent between $1,800 and $2,000 on improvements and, tellingly, codified a set of respectability rules: no liquor in the theatre or waiting room, no communication with nearby saloons, an officer on duty at all performances, ice water for patrons, souvenirs on Tuesdays and Fridays. The management promised “a continuous bill of first‑class attractions,” and—crucially—the sample roster included “a fifteen‑minute act of burlesque magic and necromancy,” novelty musical comedy, stereopticon slides, and moving pictures.

It’s a candid snapshot of the tightrope managers walked: keep the commercial electricity of burlesque’s spectacle and word‑of‑mouth while draping it in a cleaner, safer, monitored environment palatable to middle‑class families. Nationally, historians describe exactly this dynamic as burlesque and variety edged toward regulated circuits and “polite” houses.

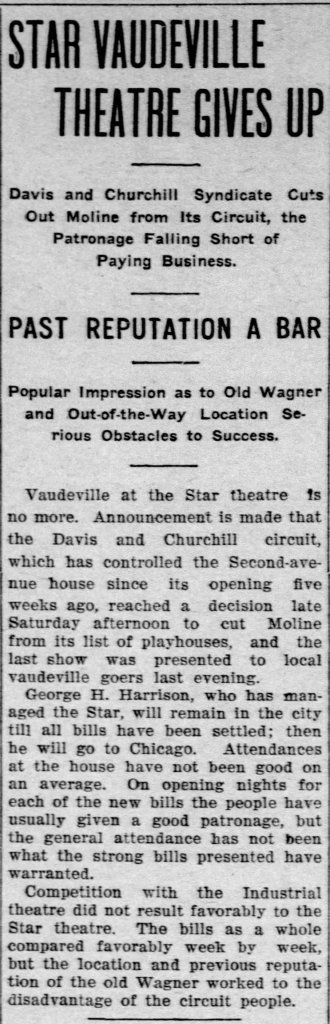

One month later, though, an article announces that the circuit has pulled out of Moline. The reason? Among others, “the location and previous reputation of the old Wagner.” Respectability is a lagging indicator; moral memory outlasts a paint job.

Labor: The Circuit and the Chorus

The playbills name specialty acts, duet sketches, magic and necromancy, living pictures, stereopticon slides, even dog and monkey shows. This is hard, routinized labor: short rehearsal windows, rapid load‑ins, wardrobe changes, and week‑to‑week content refresh to keep seats filled. The 1906 rules (security officer, no liquor, souvenir schedules) reflect the managerial discipline that came with continuous vaudeville. Burlesque companies like Sam T. Jack’s were logistics machines that depended on rail timetables, advertising copy, and chorus precision as much as they depended on jokes.

A River Town’s Appetite for Spectacle, Satire, & Reinvention

What emerges from the Wagner’s burlesque timeline is not just a record of performances, but a portrait of Moline’s cultural metabolism at the turn of the twentieth century. This was a river town in the midst of industrial growth, shaped by factory labor, immigration, and the social rhythms of a working‑class population that sought out entertainment as both escape and communal ritual. Burlesque fit that need perfectly.

Each advertisement promises novelty, humor, movement, and spectacle — frolics set in fictional hotels, satirical jabs at sports celebrities, entire companies of comedians, dancers, magicians, and specialty performers. These shows didn’t just entertain- they provided a space where audiences could see everyday norms disrupted, exaggerated, or mocked. Burlesque’s trademark blend of parody and sensuality offered a safe theatrical distance from the rigid moral codes championed by civic leaders, and the Wagner’s most successful nights were the ones when audiences embraced that inversion wholeheartedly.

The 1903 review noting an all‑male audience captures one side of that culture: a gendered leisure world where men dominated nighttime public amusements. Yet the performances themselves — filled with choreographed ensembles, comic reversals, and cleverly constructed “extravaganzas” — reveal how much discipline and theatrical intelligence were required to stage these acts, and how deeply burlesque relied on the skill and charisma of its performers. The Wagner became a place where working‑class pleasure, artistic labor, and comedic daring converged in ways that blurred the boundaries between high and low culture, propriety and play.

By 1906, when management attempted a vaudeville rebrand complete with house rules and moral safeguards, it was clear that the Wagner’s identity was already set in the public imagination. The venue’s long association with lively, bawdy, attention‑grabbing entertainment had become a cultural imprint stronger than any renovation. Burlesque wasn’t merely something that happened at the Wagner — it shaped how the community understood the space itself.

In this way, the Wagner Opera House stands as a testament to the enduring pull of popular entertainment in Midwestern river towns: audiences looking for laughter, spectacle, and a chance to step outside the ordinary; performers offering craft, charisma, and satire; and a building whose legacy was written not in arias, but in the bright, brazen energy of burlesque.

Sources

Newspaper Clippings:

- The Dispatch (Moline), Nov. 17, 1898 (ad): Stetson’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Darkest Russia.

- The Dispatch (Moline), Dec. 29, 1899 (ads): His Better Half; “VANITY FAIR—A Mélange of the Best Features of High‑Class Burlesque and Vaudeville.”

- The Dispatch (Moline), Dec. 26, 1903 (ad): Sam T. Jack’s Own Burlesque, starring Mabel Hazelton; “Two New Extravaganzas”; “Living Pictures.”

- The Daily Times (Davenport), Dec. 30, 1903 (review): “Burlesque Pleases”—largest audience to date at the Wagner; “composed entirely of men.”

- The Dispatch (Moline), Dec. 31, 1903 (ad): Vanity Fair Extravaganza Company; two burlesques for Jan. 1, 1904.

- The Dispatch (Moline), May 26, 1904 (ad): Dainty Paree Burlesquers; A Night in the Hotel Waldrough; “The Wrong Mr. Corbett.”

- The Dispatch (Moline), Sept. 1, 1906 (article): remodel and rebrand as the Star Vaudeville Theatre; rules; “burlesque magic and necromancy.”

- The Dispatch (Moline), Oct. 15, 1906 (article): “Star Vaudeville Theatre Gives Up”; “past reputation of the old Wagner.”

Websites:

Contextual Reading:

- Betsy Golden Kellem, “Burlesque Beginnings,”JSTOR Daily (June 26, 2024) — a clear overview of nineteenth‑century burlesque’s satire, gender politics, and national touring networks.

- “The Beginnings of Burlesque,”Loose Women in Tights (Ohio State University Library project) — on Lydia Thompson’s English burlesques, American touring, and the feminized authorship of the form.

Leave a comment