The Serpentine Dancer

Born in 1862 in Fullersburg, Illinois, Loïe Fuller was a performer who defied categorization. She began her career in the rough-and-tumble world of American vaudeville, burlesque, and circus acts, where skirt dancing and novelty performances were the norm. But Fuller didn’t just dance — she transformed. Her artistry fused movement, light, and fabric into a spectacle that mesmerized audiences and reshaped the possibilities of stage performance.

From Skirt Dancer to Parisian Icon

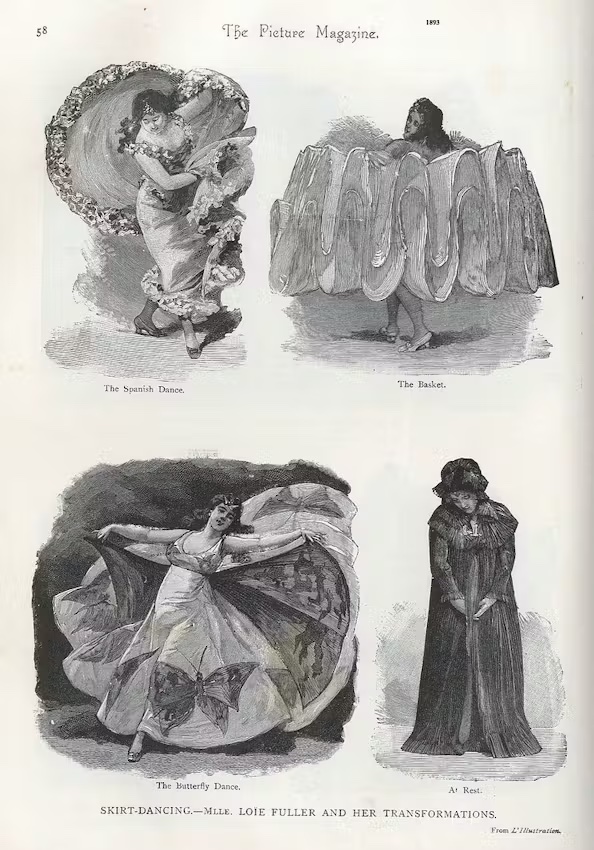

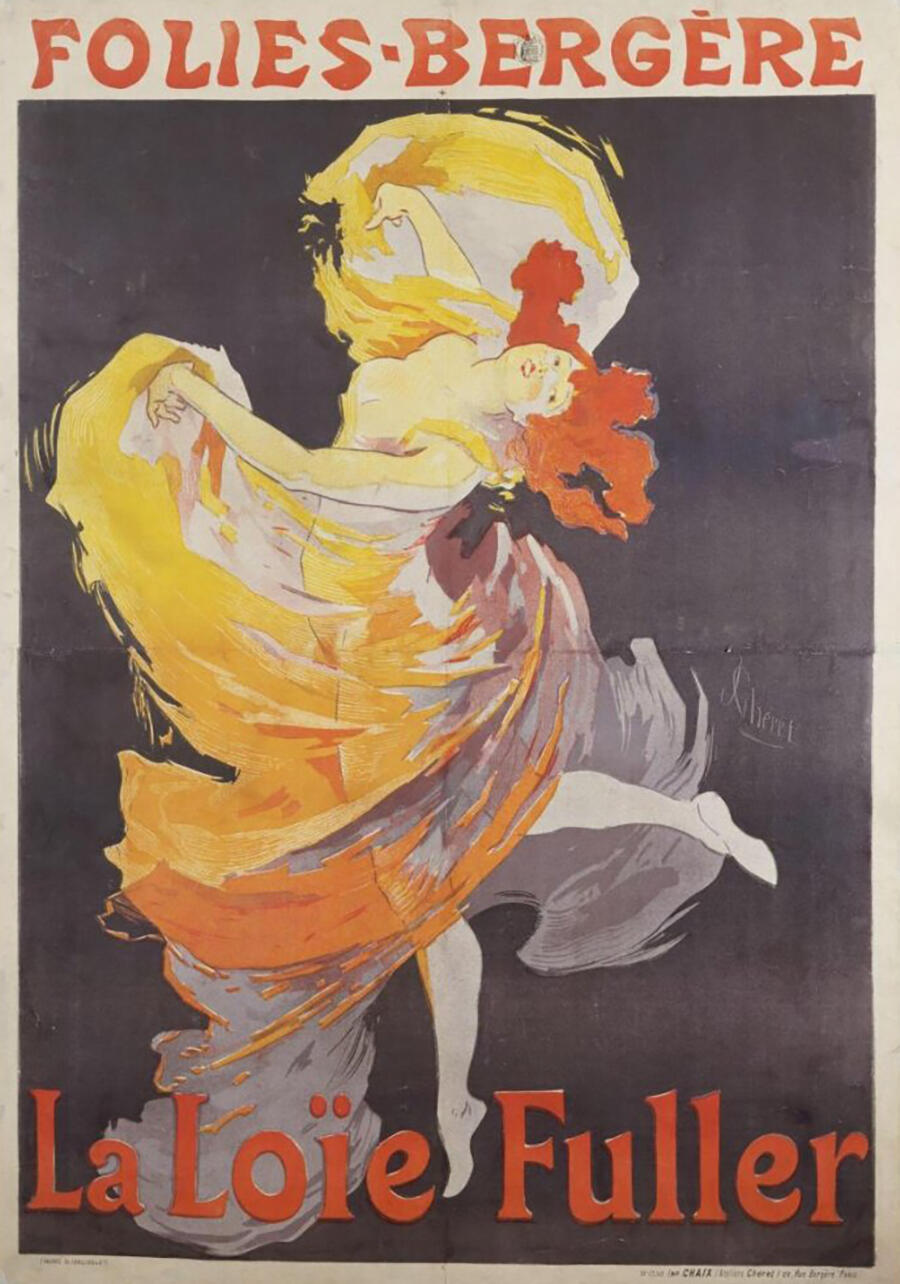

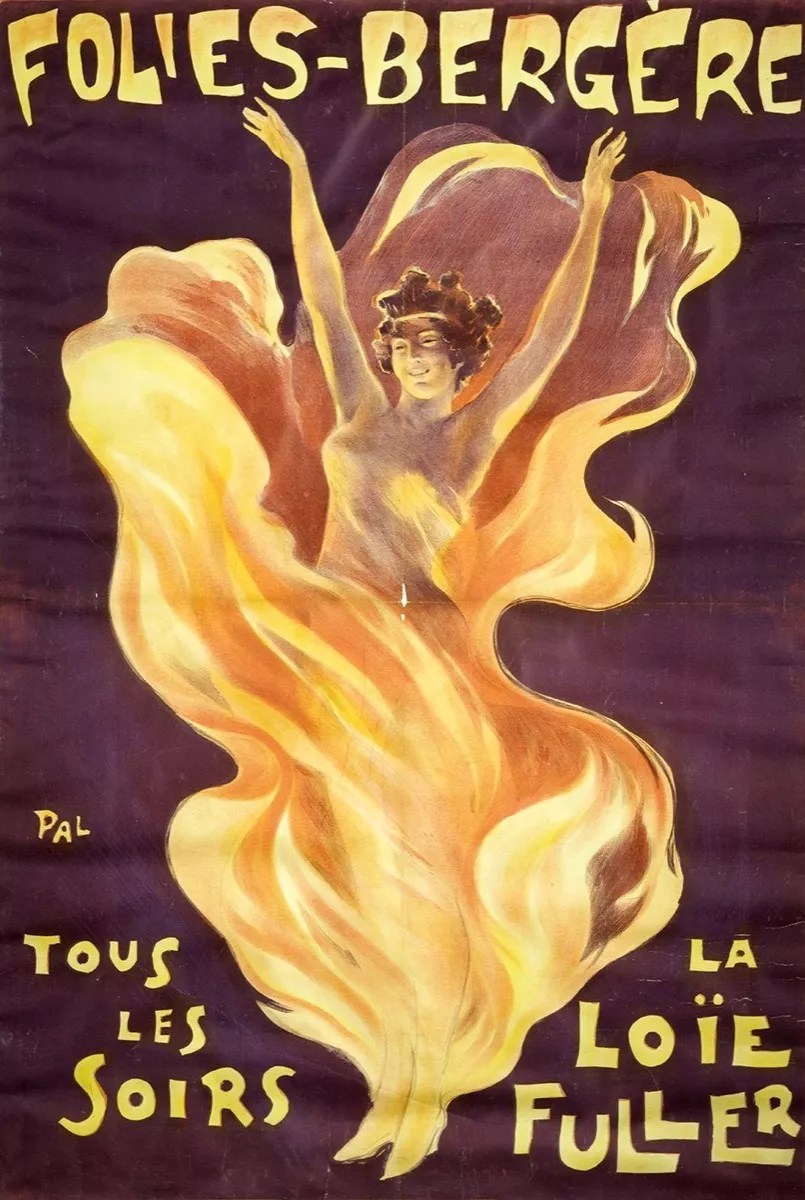

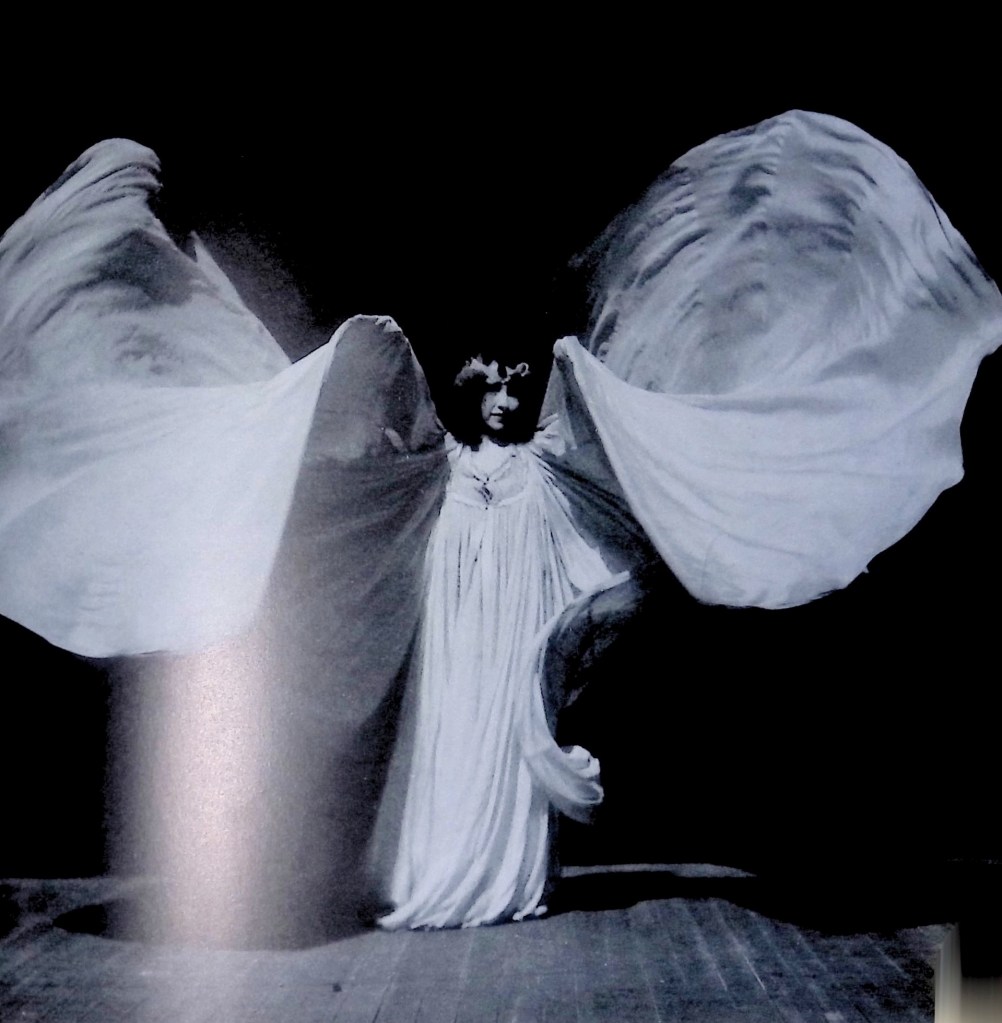

Fuller’s early years on the American stage were marked by experimentation. She performed dramatic readings, comic sketches, and skirt dances — a genre that used flowing garments to accentuate movement. But it was in 1892, after relocating to Paris, that she debuted her Serpentine Dance at the Folies Bergère. With yards of silk and colored lighting of her own invention, she created a hypnotic display of swirling forms and shifting hues. Audiences saw not a woman, but a living abstraction — fire, butterflies, moonlight.

Skirt dances were a vibrant and expressive genre that flourished in the late 19th century, particularly in burlesque and vaudeville theaters across Europe and the United States. Originating in London as a reaction against the rigid formalism of academic ballet, skirt dancing incorporated elements of popular styles like clogging and the French can-can.

These dances typically used over 100 yards of fabric, which allowed performers to create mesmerizing visual effects, especially when paired with colored stage lighting. The Gaiety Theatre in London became a hub for skirt dancing, with its chorus line of “Gaiety Girls” routinely performing the style. In the U.S., skirt dancing gained popularity as a novelty act, often performed in darkened theaters where the motion of the fabric could be highlighted by projected light.

Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine Dance was a radical evolution of skirt dancing. By shifting the focus from the dancer’s body to the costume and lighting, she introduced abstraction and theatrical innovation that prefigured modern dance. Her work added a layer of artistic and technical sophistication to a genre that had previously been seen as light entertainment, transforming skirt dancing into a medium for visual experimentation and poetic expression.

Though she lacked formal dance training and didn’t fit the era’s beauty standards, Fuller became a sensation. She was embraced by the avant-garde, befriended by artists like Toulouse-Lautrec and Rodin, and admired by scientists including Marie Curie. Her performances were hailed as visual poetry, and she became a muse of the Art Nouveau movement.

The Serpentine Dance

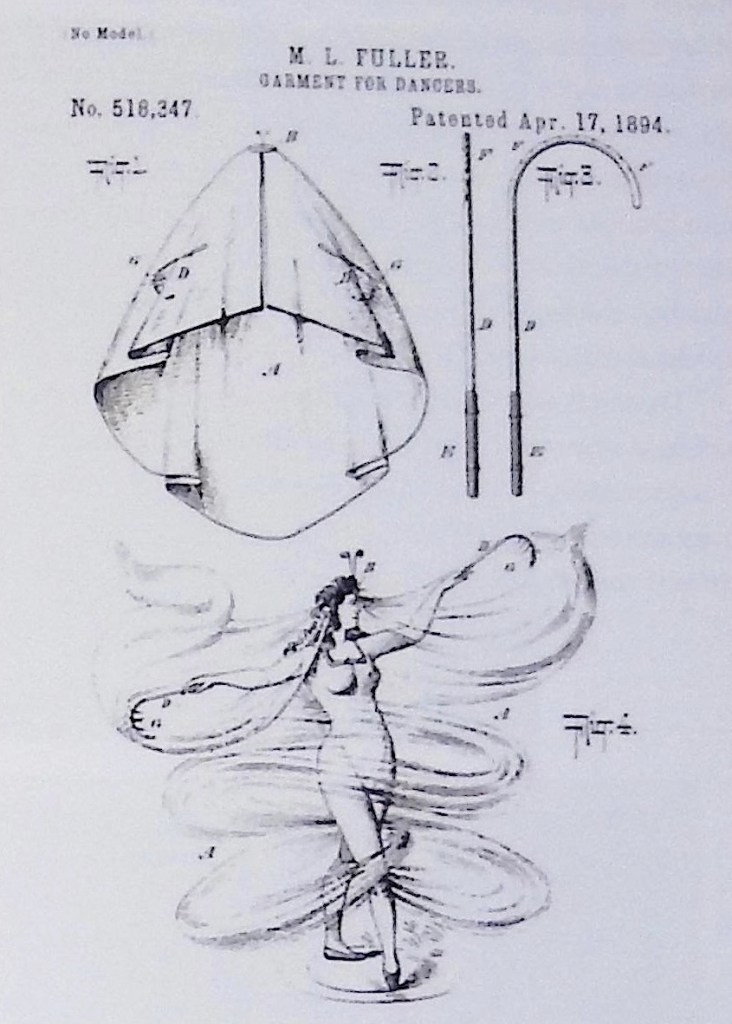

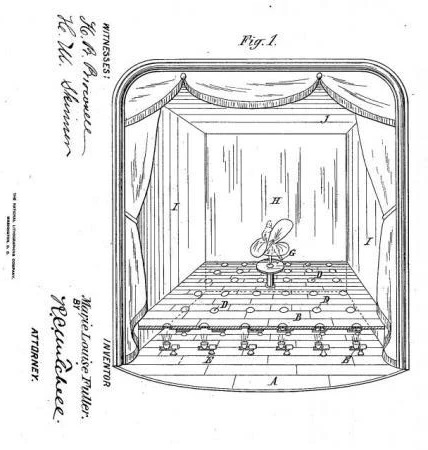

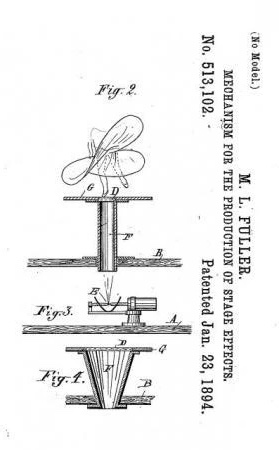

Loïe Fuller’s serpentine costume was a marvel of theatrical engineering, and she protected its design with a series of patents that underscored her role not just as a performer, but as an inventor. Her U.S. Patent No. 518,347 described a garment for dancers that incorporated bamboo or aluminum wands sewn into the sleeves, allowing her to manipulate hundreds of yards of lightweight silk into undulating shapes that mimicked fire, flowers, and butterflies.

Lighting the Way

Loïe’s lighting innovations weren’t just technical feats — they were acts of theatrical alchemy. She transformed the stage into a kinetic canvas, blending science, spectacle, and emotion in ways that were unprecedented for her time.

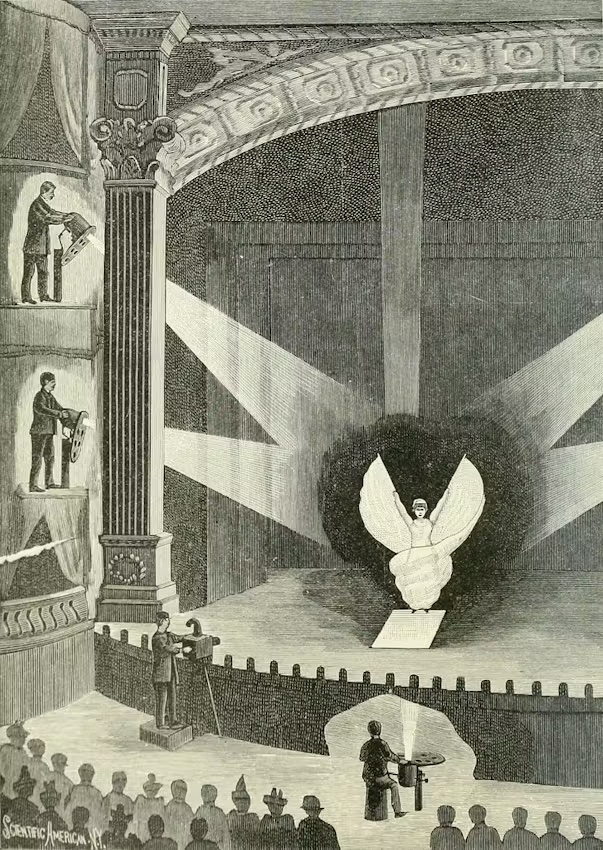

Fuller was among the first performers to use electric lighting as a choreographic element. She pioneered the use of colored gels, rotating filters, and multi-angle spotlights to tint her swirling silk costumes in real time. Her lighting wasn’t static — it moved with her, creating a dynamic interplay between dancer and environment. She even patented a stage design that included a glass floor lit from below, allowing her to appear as if she were floating in fire or moonlight.

She also experimented with phosphorescent materials and silhouette techniques, using shadows and reflections to multiply her presence on stage. In her “Fire Dance,” she required 14 electricians to manage the lighting transitions — a scale of production unheard of in the 1890s.

Fuller’s fascination with radium led her to consult with Marie Curie, though she wisely avoided using the radioactive element directly. Instead, she created a “Radium Dance” that mimicked its glow through safer means. Her lighting designs were so innovative that she was made an honorary member of the French Astronomical Society for her artistic use of light.

Fuller also patented lighting mechanisms, including sub-stage illumination and rotating color filters, which she used to tint the fabric in real time and create immersive visual effects. These innovations were so integral to her performances that she sought copyright protection for her choreography, arguing that her dances were visual compositions rather than narrative works. Though courts denied her request for an injunction against imitators, her patents helped establish her legacy as a pioneer of multimedia performance and intellectual property rights in the arts.

Influence on Burlesque

Though Fuller’s dances were abstract and non-narrative, her roots in burlesque and vaudeville remained visible. She elevated skirt dancing into high art, showing that spectacle could be both sensual and cerebral. Burlesque performers adopted her techniques — dramatic lighting, fabric manipulation, and silhouette play — to enhance the tease and theatricality of their acts.

“The soul of the dance was destined to be born in this sad and feverish age. Loïe Fuller modelled form out of a dream. Our foolish desires, our dread of mere nothing, these she expressed in her dance of fire. To satisfy our thirst for oblivion she humanized the flowers. Happier than her brothers, the lords of creation, she caused her silent deeds to live and in the darkness, this setting of grandeur, no human defect marred her beauty.”

— Gab Sorère, writing of Loïe Fuller’s dance

Fuller’s Muses

Loïe Fuller didn’t just revolutionize solo performance — she built a troupe that extended her vision and helped solidify her legacy as a choreographer, mentor, and impresario.

After achieving fame in Paris, Fuller founded her own dance company, often referred to as her “Muses.” These young women were trained in her unique style, which emphasized abstraction, fabric manipulation, and synchronized movement rather than traditional ballet technique. Fuller’s troupe performed alongside her in large-scale productions, including her celebrated “Sur la Mer immense” in 1925, where dancers manipulated vast swaths of silk to evoke the motion of the sea while being lit from below — a spectacle requiring dozens of technicians and precise coordination.

She was known to be a demanding but generous teacher, and her troupe became a kind of living laboratory for her experiments in lighting, costume, and choreography. Fuller’s dancers were often chosen not just for their physical resemblance to her, but for their ability to embody her aesthetic — fluidity, mystery, and transformation. She gave them floral nicknames like “Orchid” and “Lily,” reinforcing the symbolic and visual themes of her work.

Her company toured internationally, performing in Europe, Egypt, and the United States, and helped spread her influence far beyond the Folies Bergère. Fuller’s troupe also played a role in mentoring future stars — she sponsored Isadora Duncan’s early European performances and supported Japanese performer Sada Yacco’s Paris debut.

Timeline of Fuller’s Troupe & Collaborations

1892 – Fuller debuts the Serpentine Dance in Paris and begins performing solo at the Folies Bergère.

1893–1895 – She starts assembling her troupe, training dancers in her unique fabric-and-light choreography.

1900 – Performs at the Paris Exposition with her troupe in a customized theater equipped with state-of-the-art lighting.

1902–1910s – The troupe tours Europe and North Africa, performing large ensemble works like “La Mer” and “Les Papillons.”

1920s – Fuller’s dancers perform increasingly elaborate group pieces, requiring complex coordination and synchronized manipulation of fabric.

1925 – “Sur la Mer immense” debuts, a grand ocean-themed performance that exemplifies her ensemble staging.

1928 – Fuller passes away, but several of her dancers continue to perform her works and mentor others.

Notable Muses and Figures

Gabrielle Bloch – Known professionally as Gab Sorère, Fuller’s longtime partner and manager, Bloch was central to organizing the troupe’s tours and artistic direction. Her support enabled Fuller to focus on choreographic and technical innovation.

Isadora Duncan – While not formally part of Fuller’s troupe, Duncan was mentored by Fuller in Europe. Duncan’s emphasis on natural movement and freedom owes much to Fuller’s fluid, anti-ballet aesthetic.

Sada Yacco – A Japanese Geisha, actress and dancer whom Fuller championed during her Paris debut. Sada Yacco blended Japanese theatrical traditions with Western stagecraft, reflecting Fuller’s global influence.

The “Flower Girls” – Fuller nicknamed her ensemble dancers after flowers like Orchid and Lily, reinforcing the Symbolist themes of her work. These performers trained rigorously to master the technique of manipulating fabric in tandem with light cues, contributing to the ensemble’s dreamlike quality.

Fuller’s layered silk costumes inspired burlesque designers to think beyond corsets and rhinestones, embracing movement-driven garments that told stories through motion. Fuller’s emphasis on transformation and illusion became central to the burlesque aesthetic, especially in neo-burlesque, where artistry and abstraction are celebrated alongside glamour and satire.

Even as she aged and faced competition from younger stars like Josephine Baker, Fuller remained a respected figure in the burlesque world. She trained her own troupe, toured internationally, and continued to innovate until her final performance in 1927.

Queer Icon

Fuller shared her life with Gabrielle Bloch (also known as Gab Sorère), and they were deeply embedded in Paris’s lesbian art circles. Their partnership, both romantic and professional, was part of a broader queer creative community that challenged heteronormative norms of the Belle Époque.

Fuller’s performances abstracted the female body, cloaking it in swirling silks and light to create forms that defied gendered expectations. Rather than presenting herself for the male gaze, she transformed into butterflies, flames, and lilies—fluid, protean entities that blurred the boundaries of identity.

A Legacy in Motion

Though few verified recordings of Fuller exist, early filmmakers couldn’t resist the spectacle of the Serpentine Dance. Silent short reels, hand-tinted frame by frame, tried to mimic her undulating silk and surreal lighting effects.

Countless imitators followed, but none could match the depth of Fuller’s vision. Her influence still ripples through dance, cinema, and design. Without her, we might not have the stagecraft of concerts, the emotive lighting of theater, or the concept of performance as pure transformation.

Loïe Fuller died in Paris in 1928, but her influence endures. She helped redefine dance as a visual art, pioneered lighting techniques still used today, and gave burlesque permission to be poetic, abstract, and technically daring. Her image — swirling in silk, bathed in color — remains iconic, a symbol of transformation and creative defiance. For burlesque artists today, Fuller is more than a historical figure. She’s a reminder that performance can be invention and that beauty can be unconventional.

Sources

Websites

- https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/loie-fuller-and-the-serpentine/

- https://www.frieze.com/article/serpentine-dancer

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serpentine_dance

- https://www.britannica.com/art/dance/The-aesthetics-of-dance

- https://www.timelapsedance.com/loie-fuller-essay

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-loie-fuller-pioneering-dancer-brought-art-nouveau-life

- https://scienceandfilm.org/articles/2880/the-dancer-loe-fullers-inventions

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loie_Fuller

- https://musiqa.org/musiqa-explorer-cabaret-of-shadows/

- https://magazine.cnd.fr/en/posts/87-loie-fuller-a-subversive-pioneer

- https://academic.oup.com/book/8284/chapter-abstract/153896987?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false

Photographs

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1350515/loie-fuller-photograph-unknown/

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1350517/loie-fuller-photograph-rotary/

Films

Publications

- Linge, Ina. “Queer Ecology in Loïe Fuller’s Modernist Dance and Magnus Hirschfeld’s Die Transvestiten.” University of Exeter, UK. Department of Languages, Cultures and Visual Studies

Leave a reply to A Queer Icon: Loïe Fuller & the Watch and Ward Society – Let's Burlesque Cancel reply