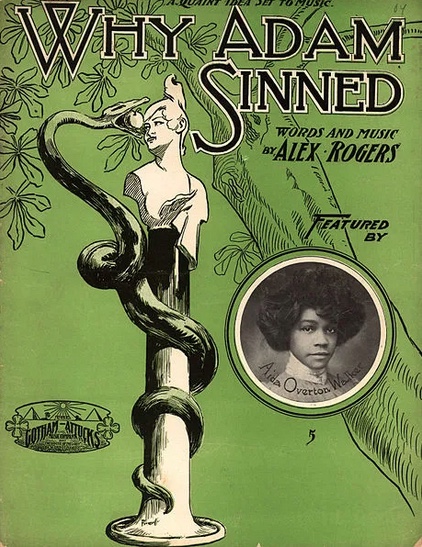

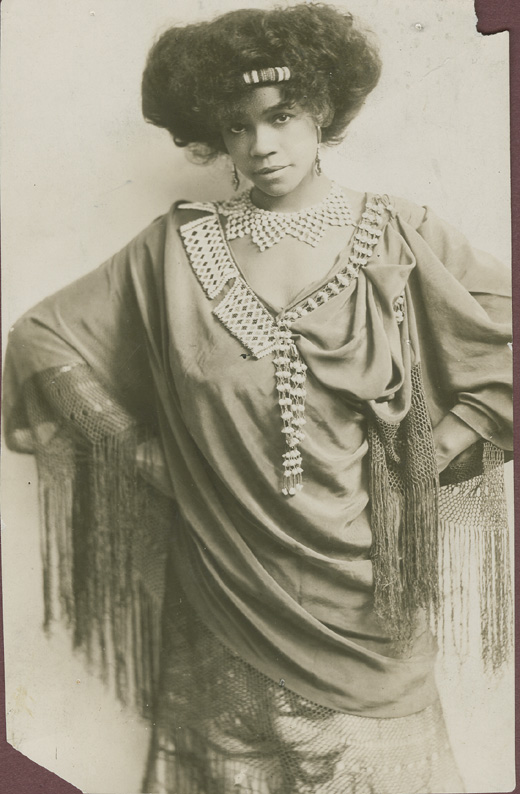

Aida Overton Walker (1880 – 1914) was a transformative figure in American performance history. As a dancer, singer, choreographer, and cultural advocate, she elevated African American artistry in an era of racial segregation and strict gender constraints. Her legacy is one of grace, defiance, and enduring influence.

Early Life & Performance | 1880-1899

Aida was born on February 14, 1880, in New York City. It’s believed her parents were from North Carolina or Virginia. There is no confirmed record of her parents’ names or occupations, and little is known of her background and upbringing. This lack of documentation is common for African American performers of the era, whose lives were often excluded from mainstream archives.

Despite the mystery surrounding her childhood, Walker’s early entry into performance suggests she was exposed to music and theater from a young age. By age 15, she was already performing in The Octoroons, one of the earliest stage shows to feature Black chorus girls. This debut placed her in the heart of New York’s vibrant Black theatrical scene during the 1890s—a time when vaudeville and musical comedy were gaining popularity.

By the late 1890s, Walker’s early performances with Black Patti’s Troubadours—a touring company named after soprano Sissieretta Jones—helped her develop stage presence, vocal technique, and dance skills. These formative years laid the groundwork for her eventual rise to stardom as one of the most influential soubrettes of her day.

The Williams & Walker Company

Bert Williams became known as “The Funniest Man in America.”

In 1898, Aida joined the Williams & Walker Company, a famous comedy team consisting of Bert Williams and George Walker. Aida appeared in all of their shows:

- The Policy Players (1899)

- The Sons of Ham (1900)

- In Dahomey (1902)

- Abyssinia (1905)

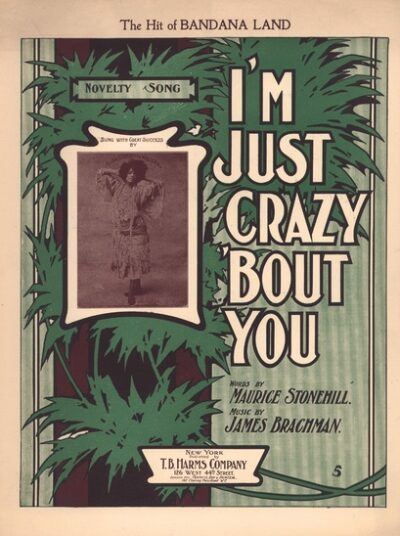

- Bandanna Land (1907)

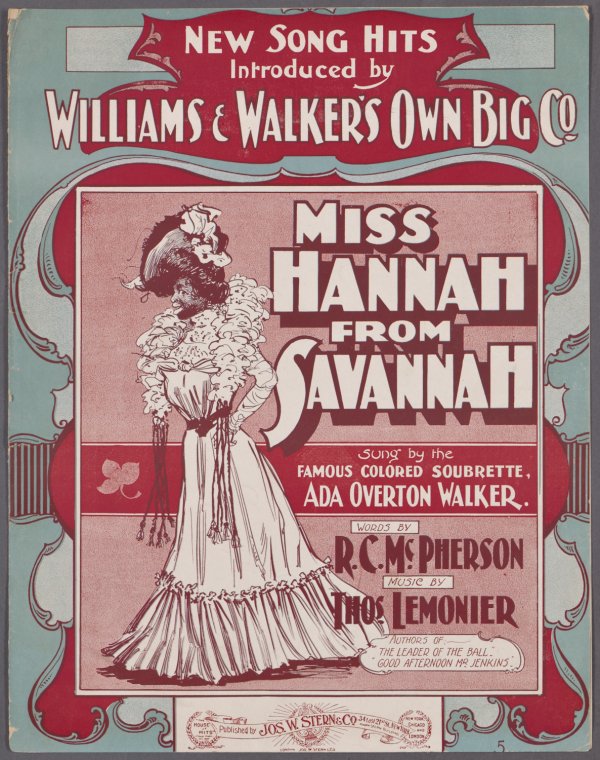

A year after meeting, she married George Walker, a vaudeville performer and producer. This marked the beginning of her rise as a leading lady in Black musical theater. Aida quickly became an indispensable member of the Company. Her acting as Hannah from Savannah in The Sons of Ham won praise for combining superb vocal control and amazing acting skills. Aida refused to comply with the plantation image of Black women as mammies, happy to serve. She, like her husband, viewed the representation of refined African American types on stage as important political work.

The Cakewalk and International Fame | 1900-1903

Between 1900 and 1903, Walker starred in Sons of Ham and In Dahomey, two groundbreaking productions that toured nationally and internationally. In Dahomey, which premiered on Broadway at the New York Theatre on February 18, 1903, was the first full-length musical written and performed by African Americans to appear on a major Broadway stage.

Walker’s performance of the cakewalk—a stylized dance rooted in plantation satire—became iconic. The production performed two seasons in England. In 1903, she performed the dance at Buckingham Palace during the company’s European tour, introducing British audiences to African American performance traditions.

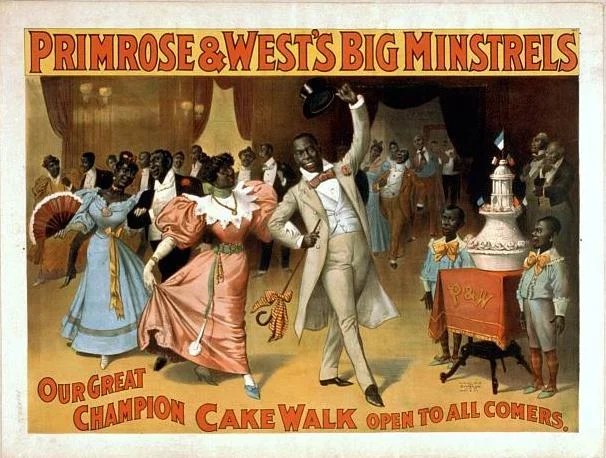

The Origins of the Cakewalk

The cakewalk began in the mid-19th century on Southern plantations, where enslaved African Americans created a dance that mimicked and mocked the formal European-style waltzes and promenades of their white enslavers. Known by names like the “chalkline walk” or “walk-around,” couples would dress in their finest attire and perform exaggerated high-stepping moves, often in front of plantation owners who failed to grasp the satire. These contests sometimes awarded a cake to the winning pair—hence the name “cakewalk”.

This dance was more than entertainment—it was a subtle form of resistance and self-expression. In a world where joy and autonomy were scarce, the cakewalk offered a moment of levity and cultural assertion. It also laid the groundwork for later African American performance traditions rooted in rhythm, parody, and style.

Aida Overton on the Cakewalk:

“It is difficult… to call the steps of the cake-walk by name. In the walk you follow the music, and as you keep time with it in what is best defined as a march you improvise. Gestures, evolutions, poses, will come to you as you go through the dance. The partners may develop steps which they think will impress the judges. Every muscle must be in perfect control.

The step of the cake-walk is light and elastic; after it has been learned fancy steps may be practiced. Some are very intricate; but the success of cakewalking depends largely on temperament, and as far as the actual steps are concerned the pupils may pass their instructors in time. The faces must be interested and joyous, and as the cake-walk is characteristic of a cheerful race, to be properly appreciated it must be danced in the proper spirit- it is a gala dance.

In dancing, all the muscles of the body are brought into play, any effort or fatigue is concealed, the shoulders thrown welll back, the back curved, and the knees bent with suppleness. The swing, all jauntiness and graceful poise, must come from the shoulders, and the toes must turn well out. The tempo is between the two-step and the march six-eight time. The Negro melodies which may be played for the dancers are without number. In the quicker numbers the women should be careful to manage their long skirts gracefully, an art which requires a good deal of practice, and beginners do well to wear the shorter skirts.

The cake-walk may be danced by any number of couples. A tall couple leads off, holding up the hands as in a barn dance. A cake is placed in the center of the room on a pedestal, the opening bars of the music are played, and the dancers march around.

The walk over, with its various features, its impromptu steps, and gaiety coming to an end, the question arises, “Who takes the cake?” The couples now march round in all solemnity and bow to the cake en passant. A halt at command when every couple has passed by. Then the master of ceremonies names the winners. The cake is carried before them by the master or one of the guests, two lines are formed of the dancers, and the happy couple dance between the lines to general handclapping. So ends the cake-dance.”

– Aida Overton Walker

Evolution of the Cakewalk

After emancipation, the cakewalk transitioned from plantation gatherings to minstrel shows and vaudeville stages. By the 1890s, it had become a staple of Black theatrical productions, with performers like Aida Overton Walker refining its presentation. Her performances elevated the cakewalk from comic relief to high art, emphasizing grace, precision, and dignity.

In 1903, Walker famously performed the cakewalk at Buckingham Palace during the European tour of In Dahomey, introducing British audiences to this uniquely African American art form. Around the same time, the cakewalk became a ballroom sensation among white Americans, ironically embracing the very dance that once mocked their social rituals.

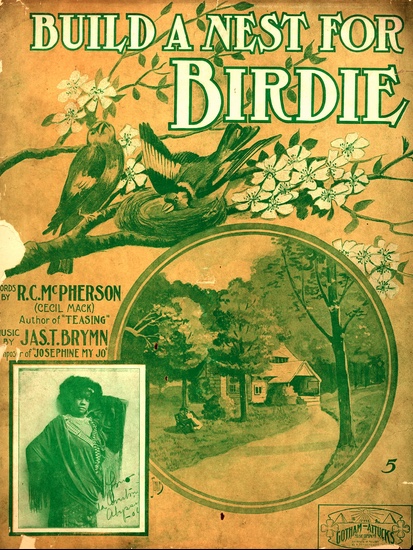

Aida’s Songbooks

Aida Overton Walker in Nebraska

Aida performed in Omaha, Nebraska in November 1904 at the Boyd Theatre with the Williams & Walker Company. They performed In Dahomey, and were well received by Omaha audiences and made several appearances in the local entertainment scene. The same month they traveled to Lincoln and performed at the Oliver Theater.

In 1906, the Company returned to Nebraska and performed their new musical Abyssinia at the Krug Theatre in Omaha and the Oliver Theatre in Lincoln. The Omaha Daily Bee reported, “Aida Overton Walker does some clever work in both singing and dancing, being graceful of limb and tuneful in voice.” (“Williams and Walker at the Krug” Page 5. October 27, 1906)

In October 1909, Aida and the Company returned to the Krug Theatre for Red Moon.

Burlesque Work and Final Years | 1910-1914

After a decade of success with the Williams and Walker Company, Aida’s career took an unexpected turn when her husband collapsed on tour with Bandanna Land. Walker had to return home to Kansas to recover from illness. In his absence, Aida took over many of his songs and dances to keep the company together and on tour. Reportedly, she dressed in male drag and performed her husband’s role.

The Broad Ax article reads: “Aida Overton Walker: still the people’s idol, wears handsome costumes, makes usual hit in male attire, she sings pleasingly. Her feet are nimble and she was given voluminous applause.” November 8, 1913 (Chicago, IL)

Dance of Salomé

In 1912, Walker starred in a solo production of Salomé at the Victoria Theater in New York. Her interpretation of the biblical figure was bold and sensual, challenging norms about race, gender, and theatrical roles. She had danced the role previously in Black venues, but her 1912 appearance marked her debut in a predominantly white theater.

The character of Salomé—often depicted performing the “Dance of the Seven Veils”—was a muse for women to command attention and subvert expectations. Walker’s interpretation was described as “commanding, sensual, and elegant,” challenging the notion that Black women could only appear on stage in comic or subservient roles. By reshaping the audience gaze, she expanded the possibilities for Black women on stage, offering a model of performance that was both glamorous and sensual.

Her Salomé was not a caricature but a complex, magnetic figure. She used costume, gesture, and choreography to evoke allure without compromising her artistic integrity. This balance between sensuality and sophistication placed her squarely within the burlesque tradition—while also redefining it.

Dark Town Follies Troupe | 1913-1915

The Darktown Follies were a series of musical revues staged at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre between 1913 and 1915. Produced by J. Leubrie Hill and featuring an all-Black cast, these shows blended ragtime music, comedic sketches, and energetic dance numbers that celebrated African American culture while challenging racial stereotypes. The first installment, My Friend from Kentucky, debuted in November 1913 and was so successful it led to sequels like My Friend from India and My Friend from Dixie.

The Follies drew racially mixed audiences, including white patrons from downtown Manhattan, and helped establish Harlem as a cultural destination. Their choreography and musical stylings influenced later Broadway hits like Shuffle Along (1921), and they provided a platform for emerging Black performers.

Aida Overton Walker, though nearing the end of her career, supported and mentored younger artists involved in the productions of the Darktown Follies. Her presence lent the Follies a sense of continuity with earlier Black theatrical movements, and her commitment to choreographing elegance and artistic integrity helped shape the tone of these vibrant, genre-defying shows.

Flo Ziegfeld and the Dark Town Follies

This moment is a striking example of how Black creativity shaped mainstream American entertainment—often without credit. The Darktown Follies, staged at the Lafayette Theatre from 1913 to 1915, were among the first all-Black musical.

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., the impresario behind the lavish Ziegfeld Follies, attended a performance of My Friend from Kentucky—the first installment of the Darktown Follies—and was captivated by its energy and originality. In 1914, he purchased the rights to “At the Ball, That’s All,” a standout number composed by J. Leubrie Hill, and restaged it with white dancers in that year’s edition of the Ziegfeld Follies.

While this act brought Black performance aesthetics to a broader audience, it also exemplifies the racial dynamics of cultural appropriation. The number’s migration from Harlem to Broadway was financially sanctioned, but the original Black creators and performers were largely erased from the spotlight. Still, the influence of the Darktown Follies endured—its choreography, musicality, and humor helped shape the revue format that would dominate American theater for decades.

End of Life

Although she was relatively young in the early 1910s, Aida began to develop medical problems that limited her capacity to be constantly touring and performing on stage. As early as 1908, she began organizing benefits to aid the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls. Once her theatrical contract ended, she devoted her life to mentoring young black actresses interested in developing their talents. Aida produced two female groups in 1913 and 1914, The Porto Rico Girls and The Happy Girls. She encouraged them to create original dance numbers and don stylist costumes on stage.

Tragically, Aida Overton Walker died on October 11, 1914, at age 34, from kidney disease. Her funeral was held in Harlem, thousands of people viewed her body, who mourned the loss of a visionary artist. The New York Age featured a lengthy obituary on its front page.

Sources

Websites:

- Aida Overton Walker: Female African-American Superstar by David Soren – The American Vaudeville Museum & UA Collections

- Aida Overton Walker Broke Stereotypes: Victorian Era Stage

- Aida Overton Walker (1880-1914) – Find a Grave Memorial

- Aida Overton Walker: Legacy of the Queen of the Cakewalk

- How to Cake Walk, by Aida Overton Walker (1903) – The Syncopated Times

- Slices of the Tenderloin #7: Aida Overton Walker – Chelsea Community News

- Aida Overton Walker – Wikipedia

- The True Story Of The First Drag King

- The Extraordinary Story Of Why A ‘Cakewalk’ Wasn’t Always Easy : Code Switch : NPR

- She was the Queen of the Cakewalk and the Most Famous Black Woman of the Gilded Age

- Darktown Follies – Wikipedia

- Black Theaters in NYC, an almost forgotten history

- Broadway: The American Musical

- November 16 — NY 1920s

Books

- Johnson, James Weldon. Black Manhattan. (1930) Hachette Books, 1991

Leave a reply to Guess Who’s Back! Ann Corio and Aida Overton Walker – Let’s Burlesque Cancel reply