In the golden age of jazz and burlesque, Madeline Jackson, professionally known as Sahji, emerged as one of the most mesmerizing performers of her time.Born in around 1919, Sahji rose to theatrical prominence in the 1930s and 1940s as a “shake dancer”—a style rooted in rhythm, sensuality, and improvisation. Her performances were often described as “poetry in motion,” a phrase that captured both her technical finesse and emotional storytelling.

Madeline’s Early Life

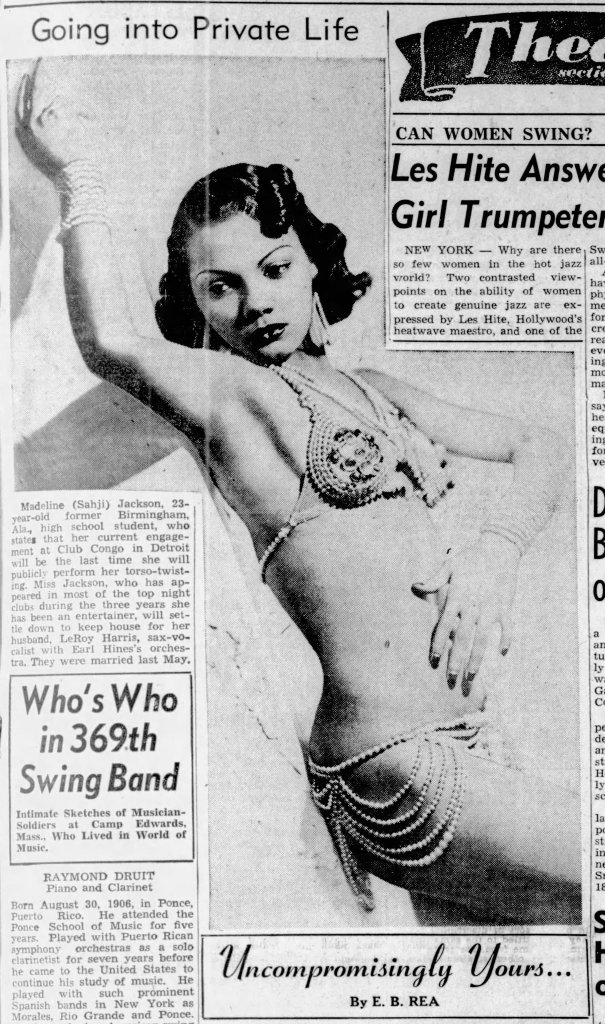

While Sahji’s stage career is relatively well documented through promotional materials, film appearances, and nightclub listings, her early life remains elusive. She was born around 1919 in Birmingham, Alabama. This regional attribution aligns with the migration patterns of many Black performers during the early 20th century—moving from Southern cities to entertainment hubs like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles in search of opportunity.

A Budding Burlesque Career

Sahji’s career began in New York City, where she performed at the legendary Cotton Club between 1933 and 1939. This venue, known for showcasing Black talent to predominantly white audiences, was a launchpad for artists like Duke Ellington and Lena Horne. Sahji’s routines stood out for their elegance and originality. She crafted her own costumes—often daring, always glamorous—and used every inch of her body to convey narrative and mood.

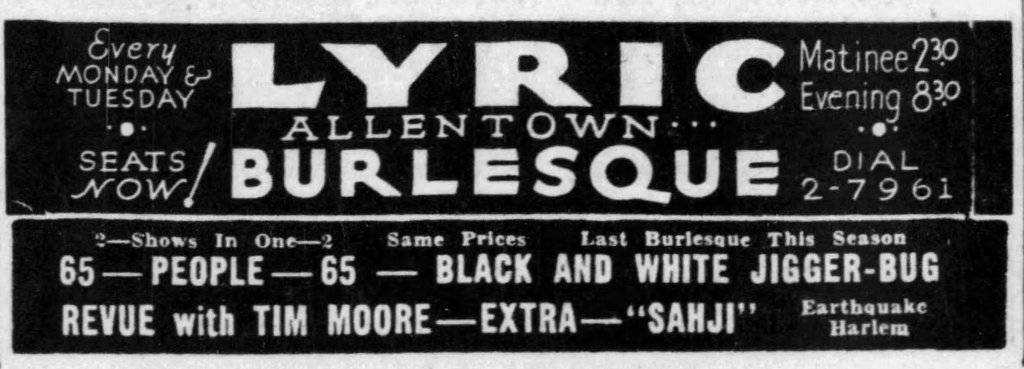

In 1938, Sahji appeared as a solo act at the Lyric Theatre. Her burlesque career took off from there–she was booked in Chicago, Detroit, and continued dancing through the Black circuit in New York City.

In 1938, Sahji expanded her repertoire by partnering with a male dancer billed as “Flash,” forming an adagio duo that brought dramatic flair and technical sophistication to the burlesque stage. Sahji also began performing a ‘serpentine dance.’

The New Pittsburgh Courier reported,

“Madeline ‘Sahji’ Jackson, one of the young pioneers who is blazing new trails, so to speak, in the bigger theatres and night clubs of the country and helping to keep alive the tradition already established by a long line of sepia entertainers.”

– “One of the Younger Pioneers.” Page 20. April 16, 1938

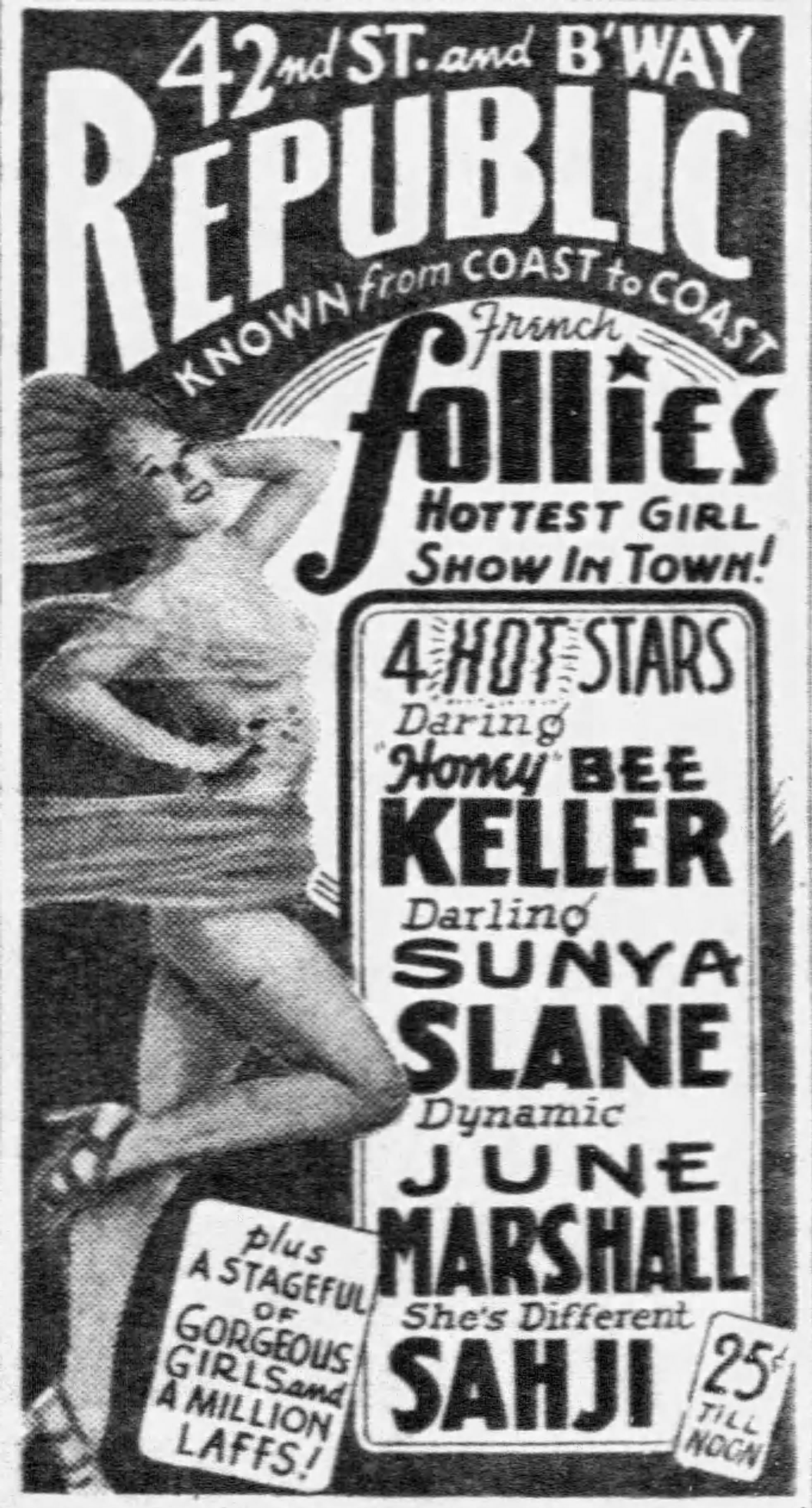

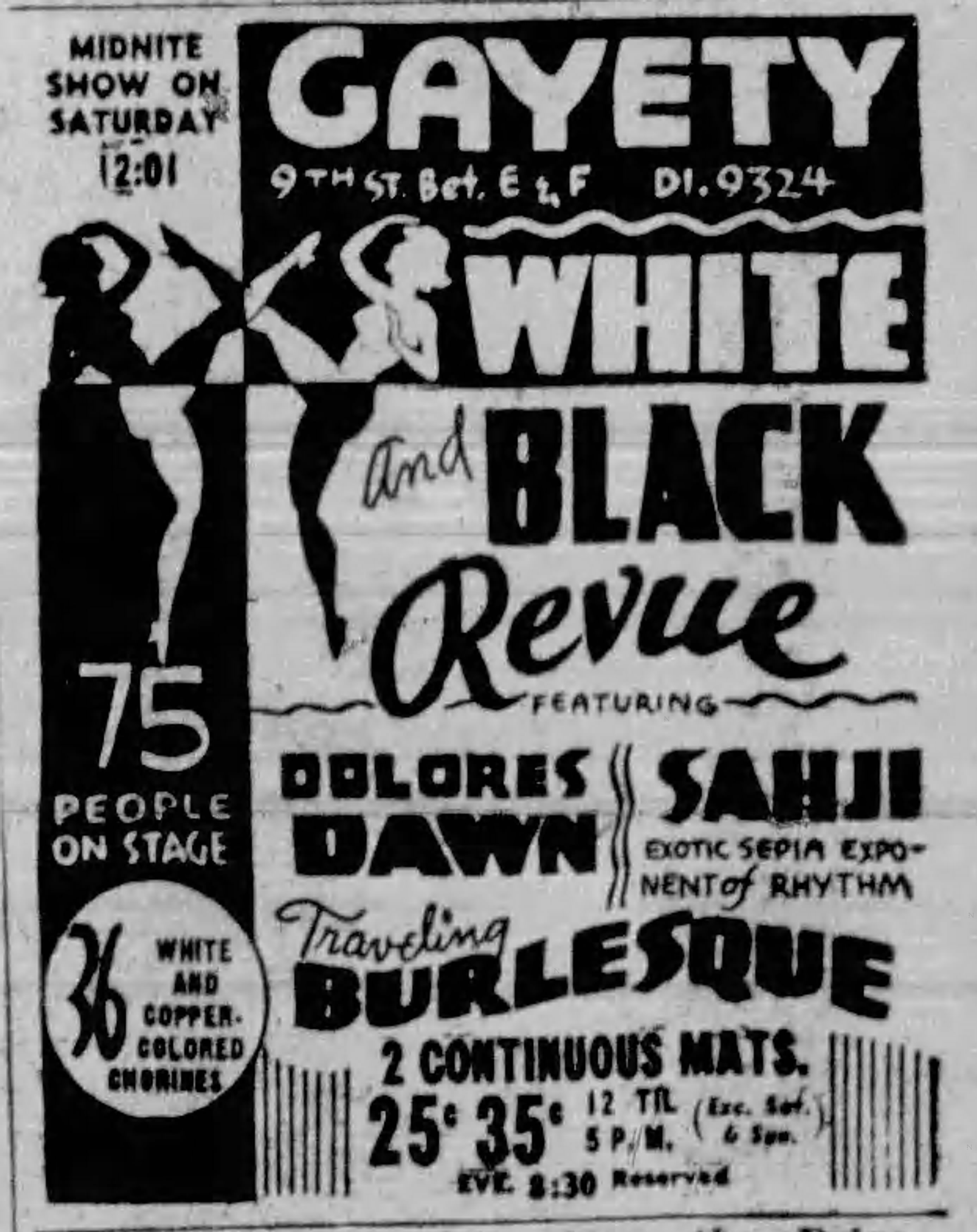

Sahji was featured with other famous white burlesquers of the time, such as Georgia Southern, Betty Rowland, and June March at the Gaiety Theater, NYC. She was billed as “the Harlem Earthquake” and the “Queen of Shake Dancers.”

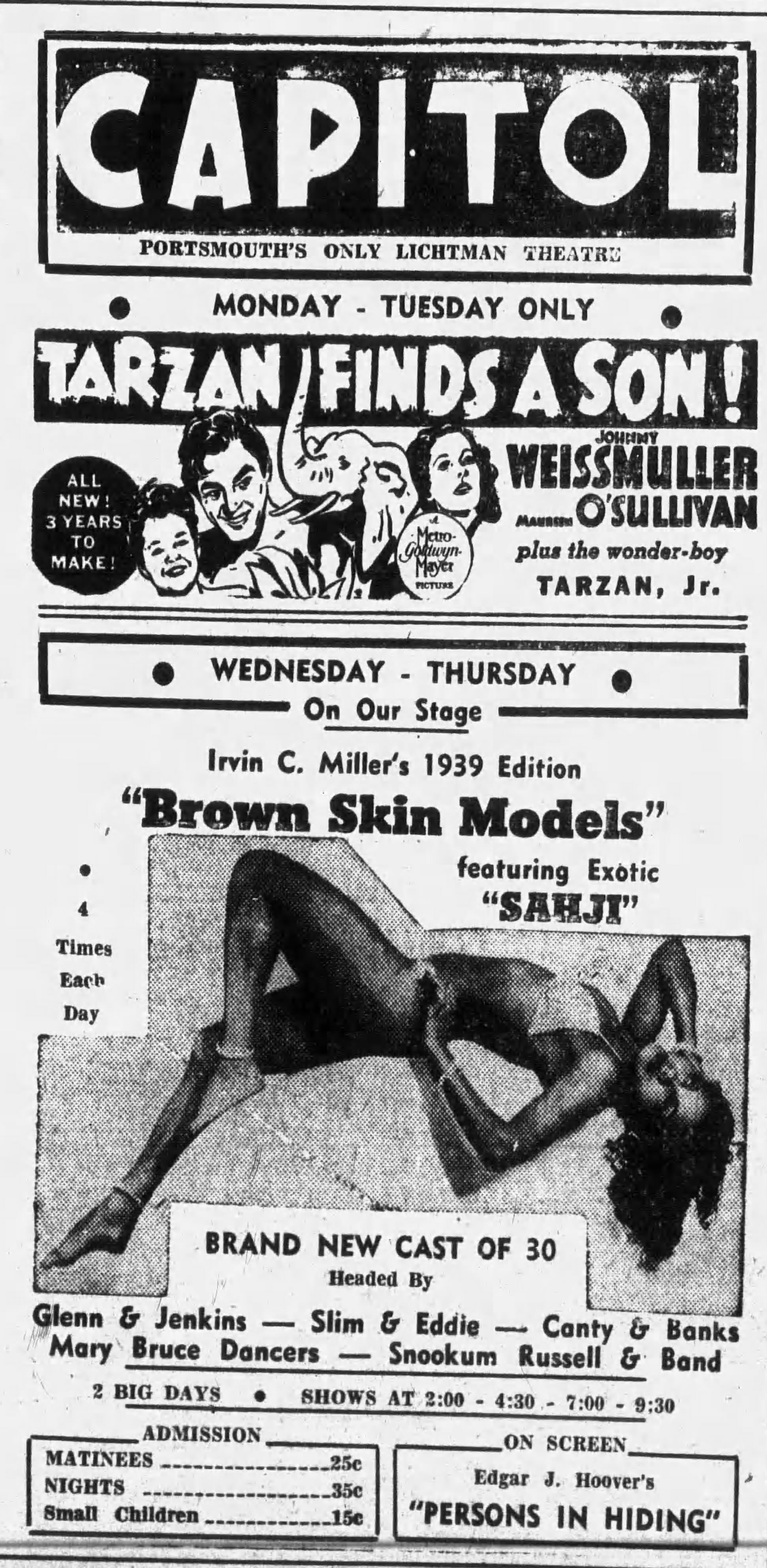

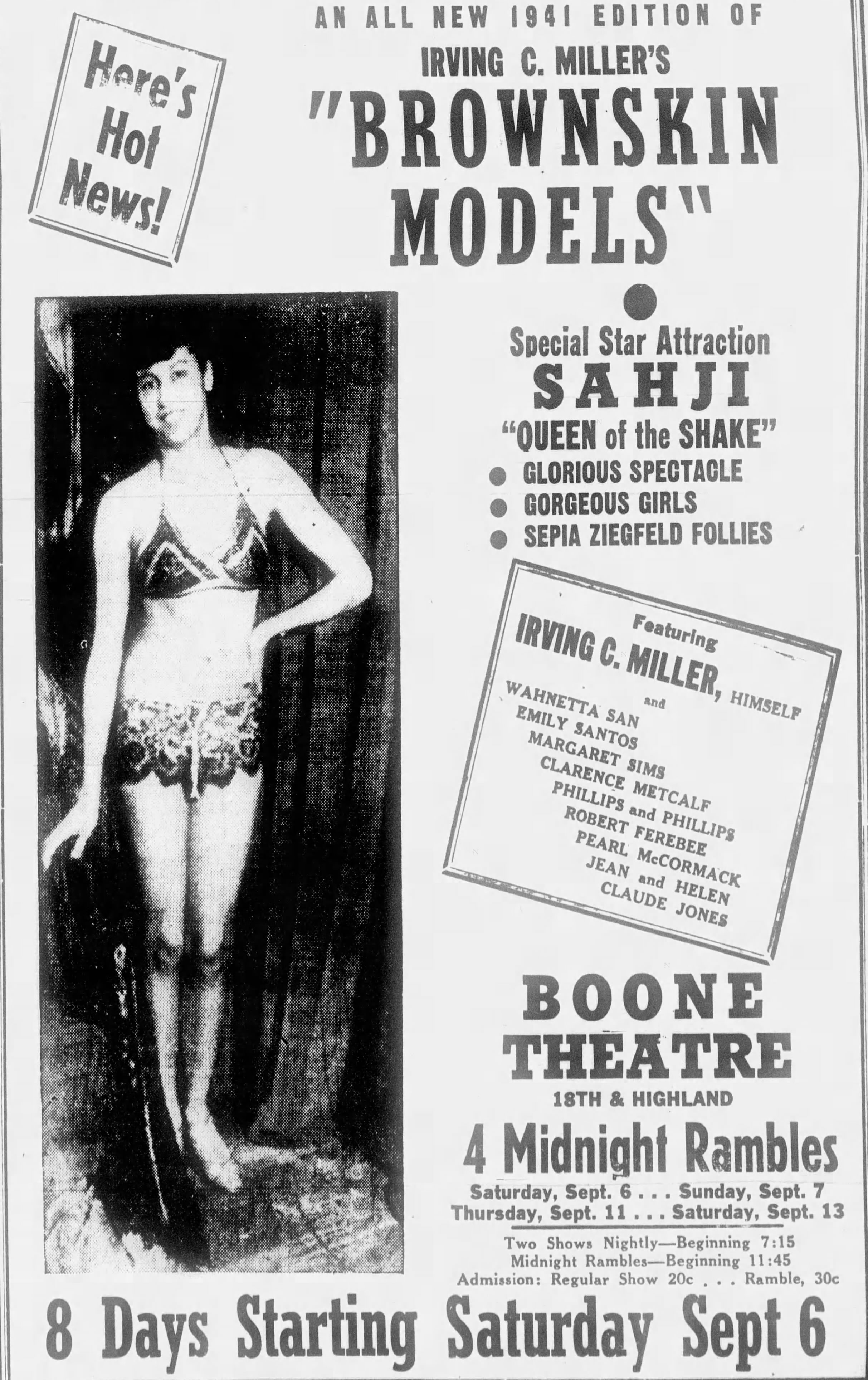

In 1939 and 1941, Sahji starred in Irving C. Miller’s “Brownskin Models”, a show that boasted the “Sepia Ziegfeld Follies.”

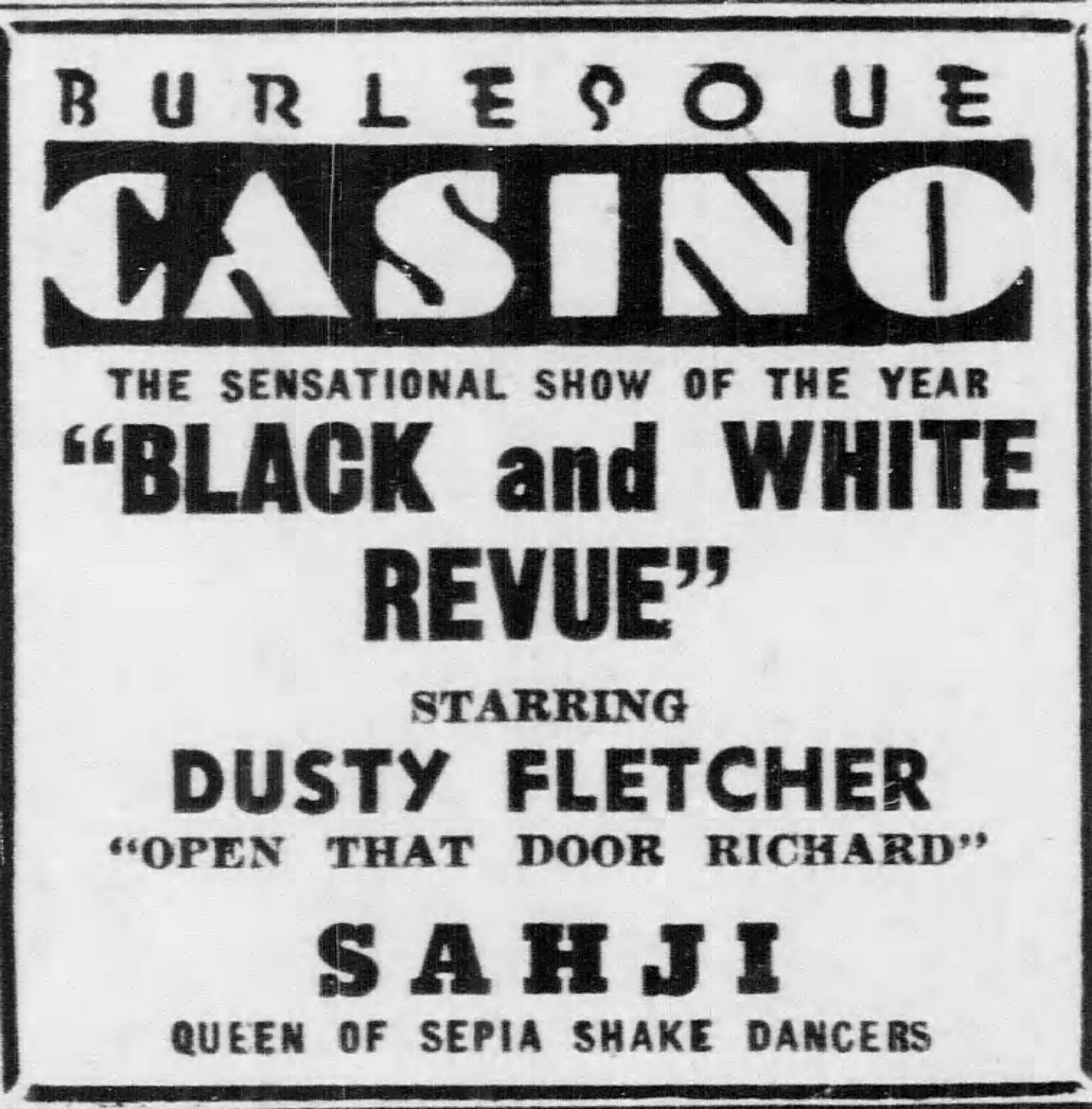

The “Black and White Revue” | 1938-1941

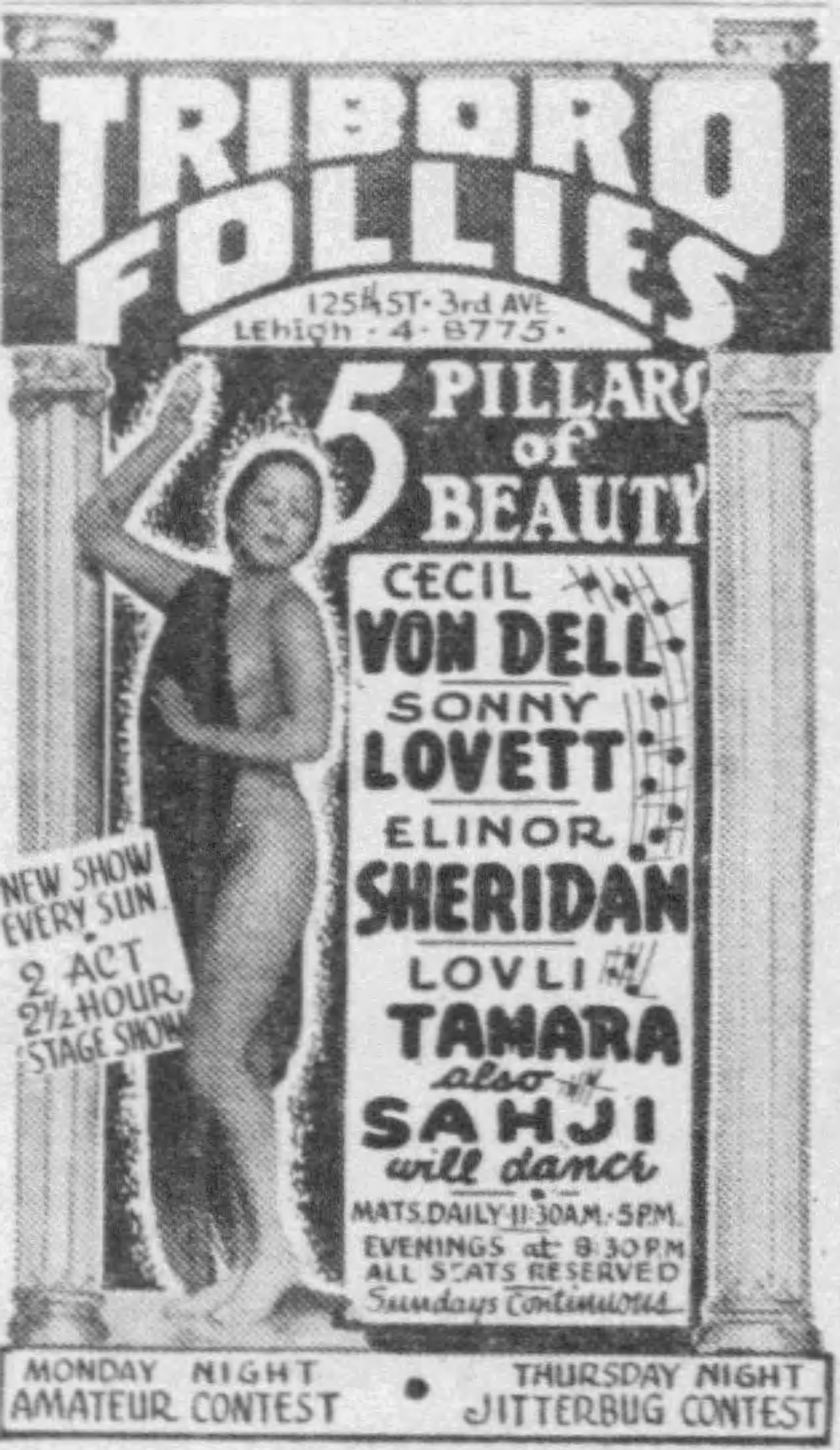

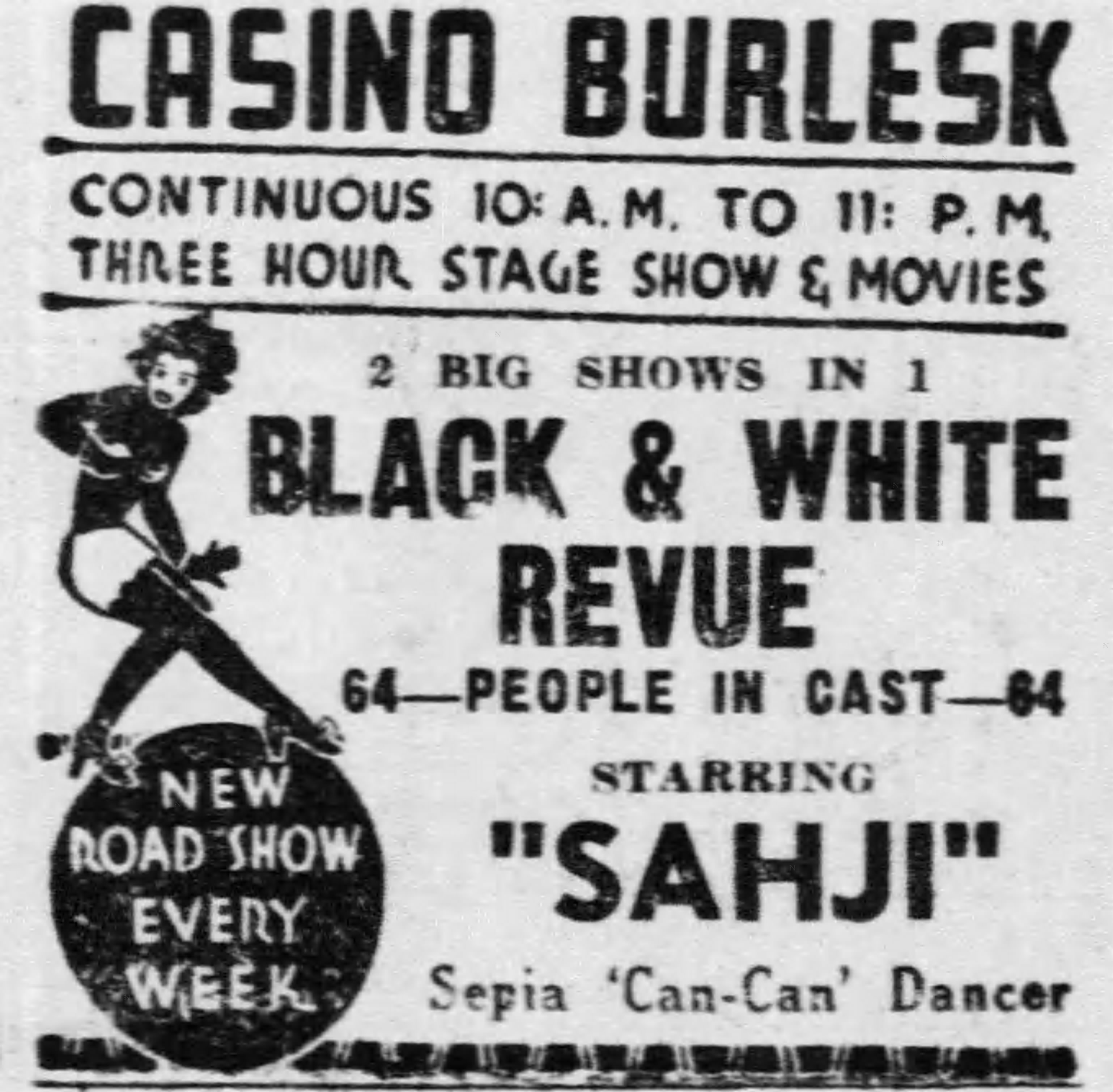

From 1938 to 1941, Sahji was featured in Ola and Eddie’s Black and White Revue, a touring burlesque and variety show that broke ground with its integrated format. The revue included two casts—one Black, one white—each showcasing standout performers in comedy, music, and dance. Overall, the cast boasted 60 performers to entertain. While segregation was still deeply entrenched in American entertainment, this revue offered a rare space where Black artists could headline and be celebrated for their artistry.

Sahji, billed as one of the principal dancers in the Black cast, brought elegance and technical brilliance to the stage. Her routines stood out not just for their sensuality, but for their narrative depth and emotional resonance.

“Madeline ‘Sahji’ Jackson went through her hip-tossing act which rocked the house with applause.” – New Pittsburg Courier. “New Mimo Club Revue Not Up To Standard.” by Major Robinson. Page 20. September 27, 1941

The revue toured major cities and was praised in entertainment columns for featuring worthwhile entertainers across both casts—a subtle but meaningful acknowledgment of Black talent in an era of limited visibility. Sahji’s presence in the show helped elevate the status of Black burlesque performers and challenged the racial boundaries of mid-century nightlife.

The New York World’s Fair? | 1939

Newspapers in Chicago spread rumors she may have performed at the World’s Fair but I couldn’t find other documentation of her performance. It would not be unlikely for a Black shake dancer to appear in one of the many revues at Fairs.

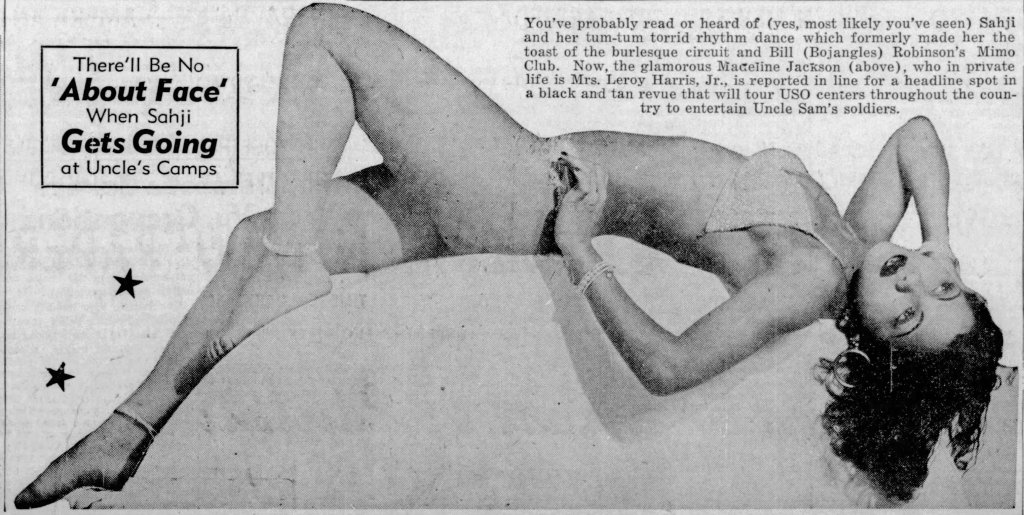

Sahji continued touring the burlesque circuits and in 1942 she joined as a headliner in an integrated revue that toured USO Centers, entertaining military troops.

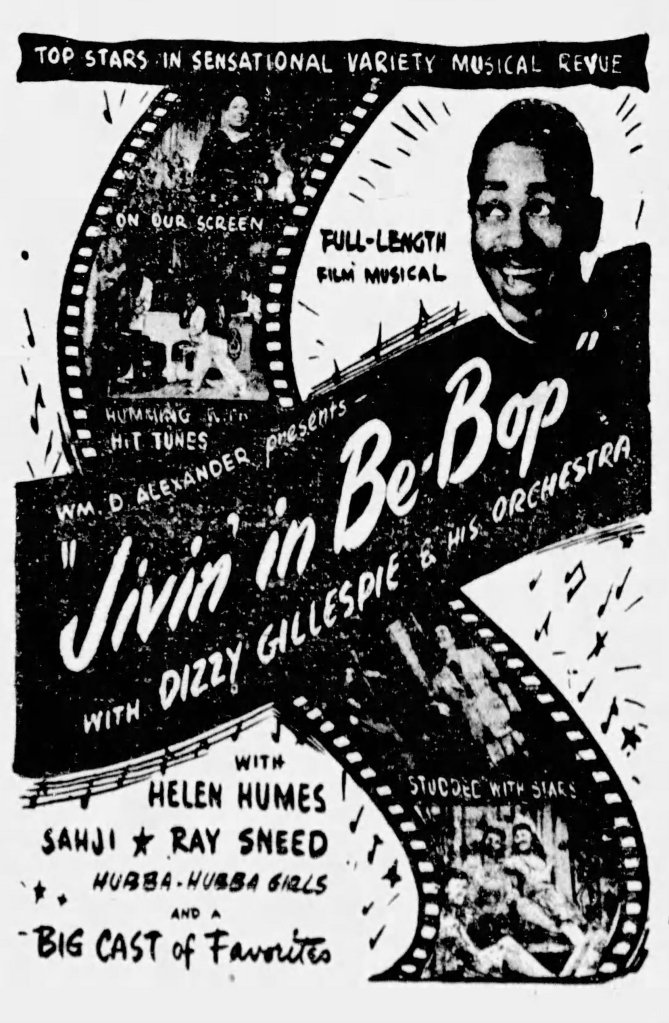

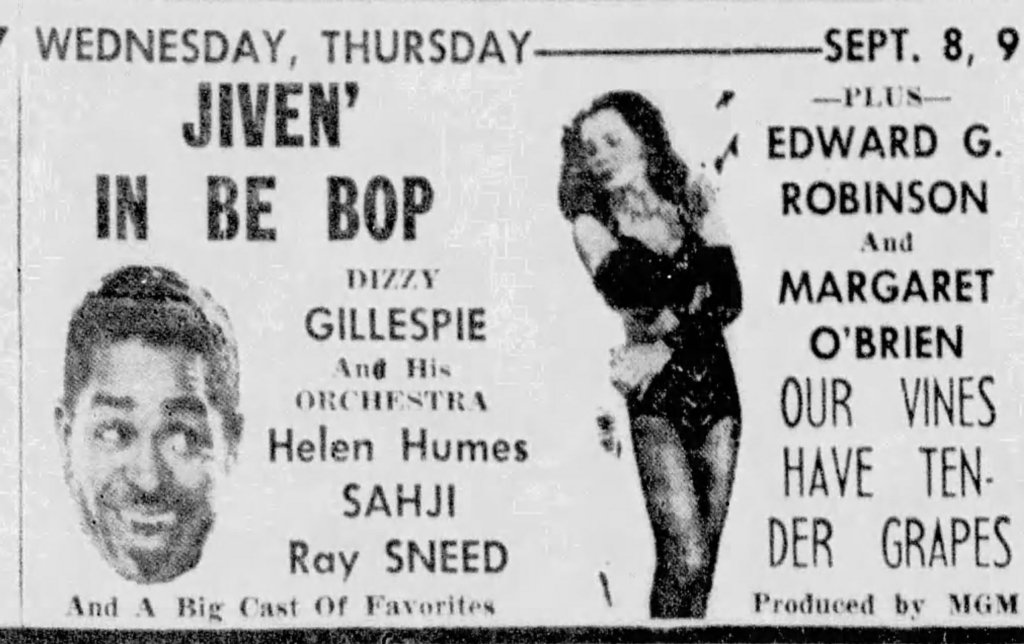

“Jivin’ in Be Bop” Film | 1946

One of the few surviving glimpses of Sahji’s artistry comes from the 1946 musical short Jivin’ in Bebop, a loosely structured film featuring performances by Dizzy Gillespie and his band. In a standout solo, Sahji appears in a shimmering costume, moving with fluid precision and emotional depth. Her routine blends elements of shake dancing with lyrical, almost balletic gestures—each movement deliberate, expressive, and deeply felt.

Though the film itself lacks narrative cohesion, Sahji’s segment offers rare visual documentation of her style: elegant, sensual, and unmistakably hers. This footage remains one of the only known recordings of her work, making it a vital artifact for historians of burlesque and Black performance.

“Boogie in C” in ‘Jivin’ Be Bop’

Set to Gillespie’s energetic composition, “Boogie in C” opens with Sahji emerging in a shimmering costume, her movements tightly synced to the rhythm. Her dance blends shake technique with fluid arm gestures and expressive isolations, creating a dynamic interplay between jazz and burlesque. Unlike many burlesque routines of the time that emphasized spectacle, Sahji’s choreography is narrative and emotive—each gesture seems to tell a story.

The number is notable for its camera work as well: close-ups linger on Sahji’s face and hands, emphasizing her control and charisma. The lighting and staging frame her as both dancer and storyteller, elevating the routine beyond mere titillation. For historians and performers alike, “Boogie in C” offers a rare glimpse into Sahji’s artistry and the aesthetics of Black burlesque in the 1940s.

Though Jivin’ in Be-Bop was not widely distributed and often dismissed as a novelty film, it has become a crucial artifact for those studying Black performance history. Sahji’s appearance—especially in “Boogie in C”—cements her legacy as a dancer who brought elegance, precision, and emotional depth to the burlesque stage. The film was popular from its release in 1946 through 1948.

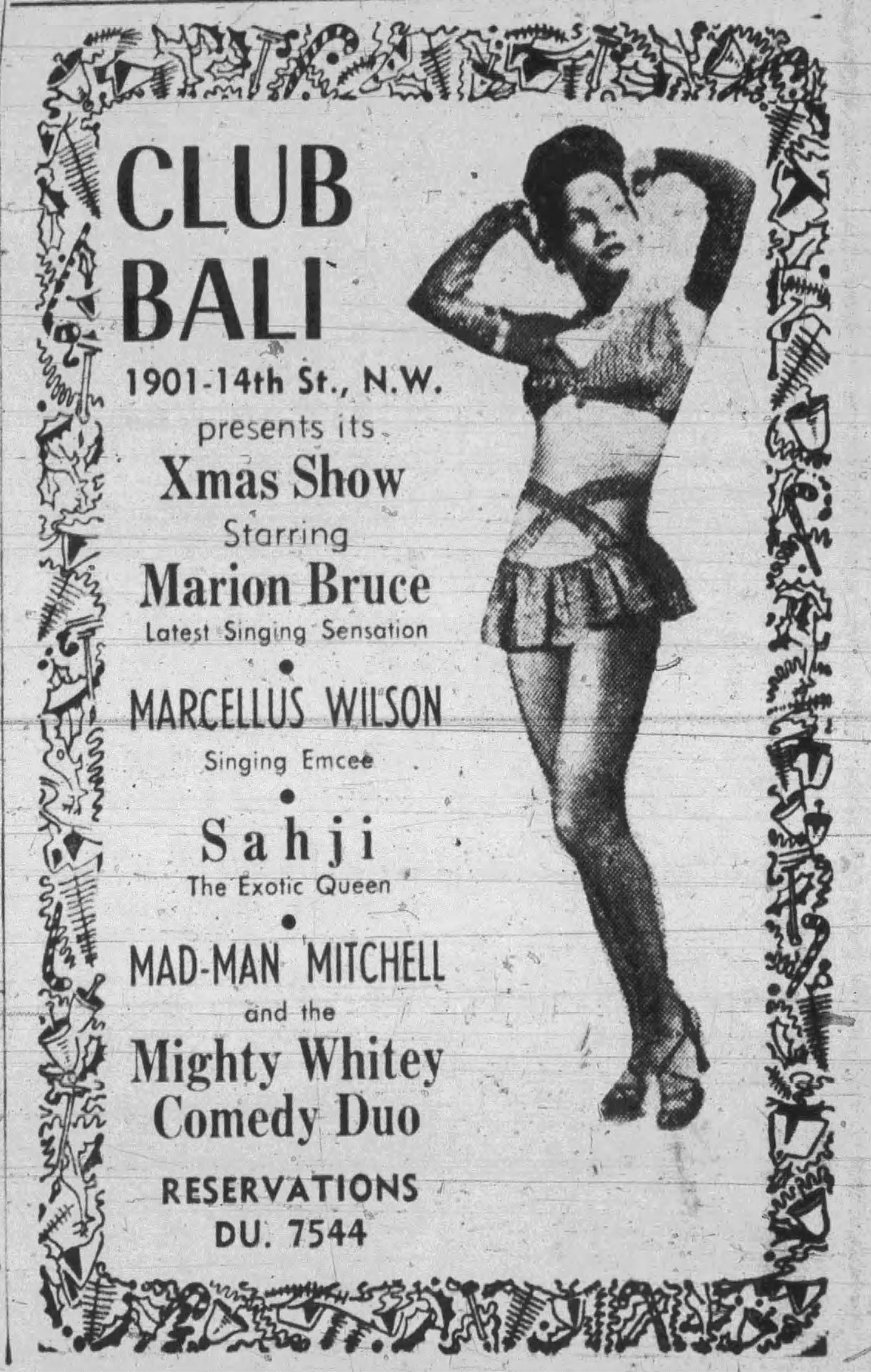

The Queen of Shake Dance

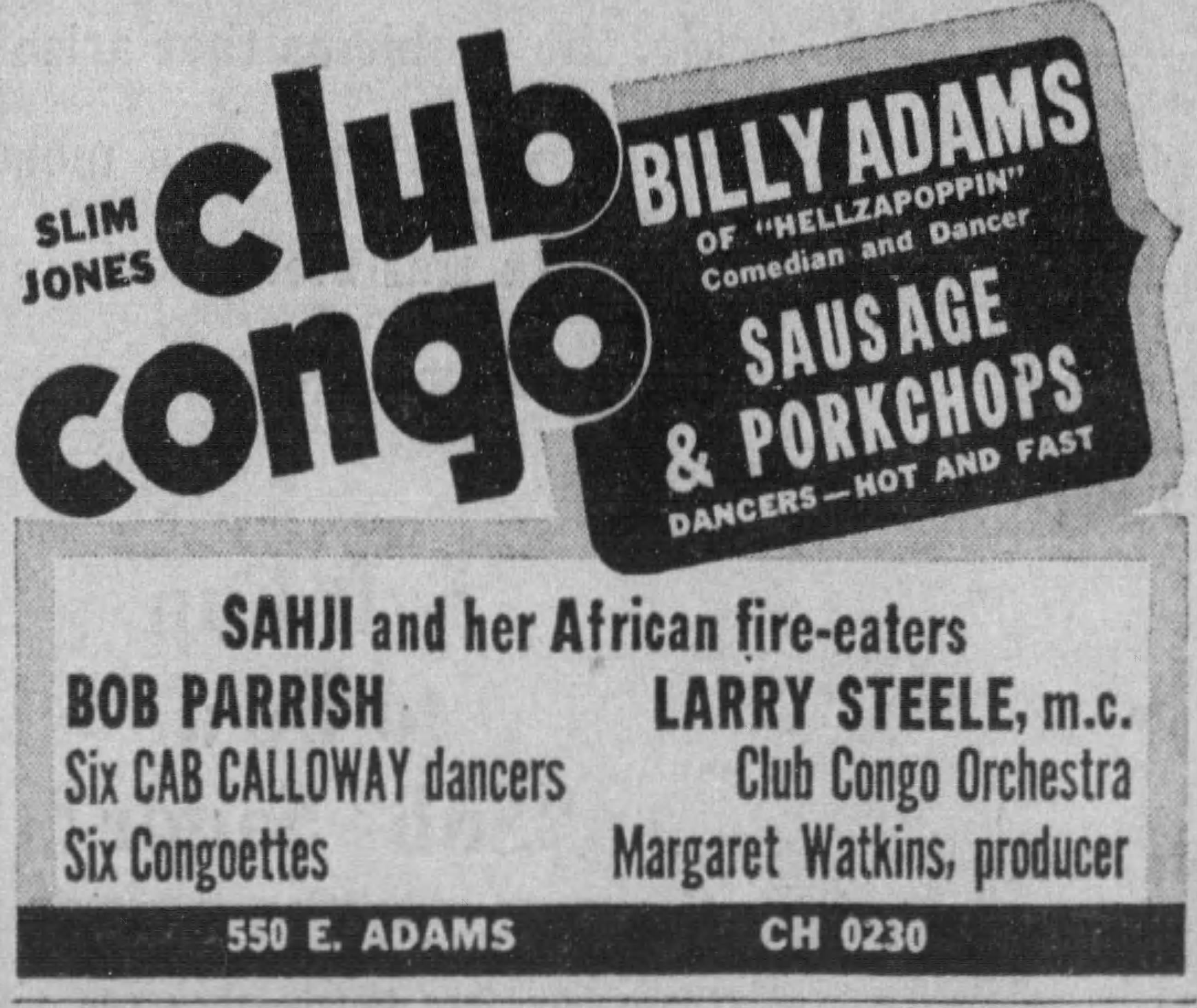

Sahji continued perform across the US soon traveling with “African fire-eaters”.

Marriage & Personal Life

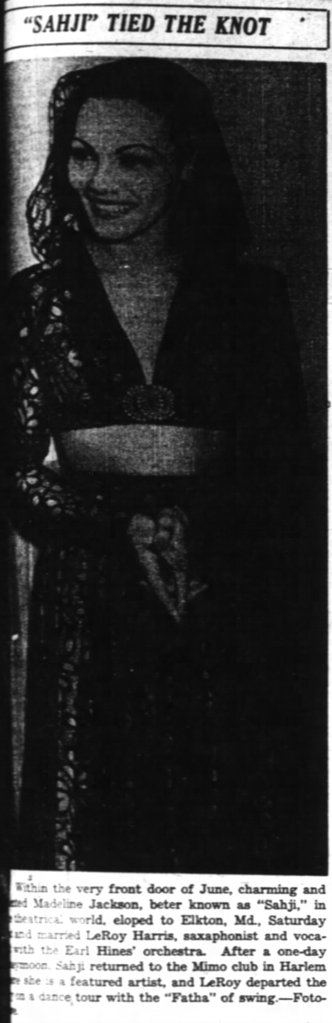

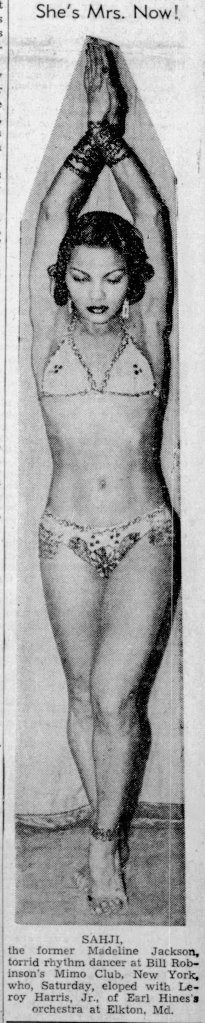

Sahji was briefly engaged to a man named Jimmy Johnson in 1939. The engagement ended that same year. She went on to marry Leroy Harris Jr., a saxophonist with the Earl Hines Band in 1941, further connecting her to the jazz world. She eventually retired from shake dancing and decided to pursue singing in the late 1940s. She went to South America and toured there for two years before returning to the US briefly and then retreating to Canada to sing songs with “slightly-resque patter.”

Though much of her personal life remains undocumented, her impact on Black burlesque and exotic dance is undeniable. She challenged stereotypes, elevated the genre, and carved space for Black women in an industry that often marginalized them.

Why Sahji Matters Today

In an era when Black women were rarely afforded space to be seen as glamorous, artistic, or autonomous, Sahji carved out a stage for herself—literally and figuratively. Her performances weren’t just entertainment; they were acts of embodied resistance. Through movement, costume, and presence, she challenged dominant narratives about race, gender, and sexuality.

1. Reclaiming Black Glamour and Agency

Sahji’s work defied the limited roles available to Black women in mid-century America. At a time when mainstream media often portrayed Black femininity through stereotypes of servitude or hypersexuality, Sahji offered a counter-image: poised, elegant, and in control of her own narrative. Her choreography wasn’t just sensual—it was intentional, blending shake dance with lyrical storytelling that demanded emotional engagement from her audience.

2. Archival Visibility and Cultural Memory

Very few Black burlesque performers from the 1930s–1950s were documented, let alone filmed. Sahji’s appearance in Jivin’ in Be-Bop and promotional materials from the era offer rare visual records of Black performance aesthetics. For archivists, historians, and performers today, these fragments are invaluable. They help reconstruct a lineage of Black artistry that has long been overlooked or erased.

3. Artistic Lineage and Influence

Sahji’s style—rooted in jazz rhythms, expressive isolations, and theatrical flair—laid groundwork for future generations of performers. Contemporary burlesque artists, especially those reclaiming space for BIPOC and queer bodies, draw inspiration from figures like Sahji. Her legacy lives on in the way dancers today blend sensuality with storytelling, and in how they use the stage to challenge norms.

4. Intersection of Burlesque and Advocacy

Sahji’s career also invites us to rethink burlesque as a site of advocacy. Her presence in predominantly Black entertainment circuits, her marriage to jazz musician Leroy Harris Jr., and her refusal to conform to white beauty standards all speak to a broader politics of visibility. Today, as performers and scholars work to decolonize the archive and uplift marginalized voices, Sahji’s story becomes a rallying point—a reminder that glamour can be radical, and dance can be a form of protest.

Sources

Advertisements

- Baltimore Afro American. Ad for “Jivin in Be Bop”. Page 18. June 19, 1948

- Daily News. Ad for Sahji at the Republic Theater. Page 57. March 31, 1939

- Daily News. Ad for Sahji. Page 38. October 23, 1939

- Detroit Free Press. Ad for Sahji at Club Congo. Page 11. April 25, 1942

- Pittsburgh Post Gazette. Ad for Sahji at Casino Theater. Page 33. January 1, 1940

- The Buffalo News. Ad for Black and White Burlesk Show. Page 12. July 18, 1941

- The Call. Ad for Brownskin Models and Sahji. Page 33. September 5, 1941

- The Morning Call. Ad for Sahji at the Lyric Theatre. Page 11. April 23, 1938

- The Pittsburgh Press. Ad for Sahji and the Black and White Revue at the Casino. Page 5. March 6, 1939

- The Portsmouth Star. Ad for Sahji at the Capitol Theater. Page 18. October 8, 1939

- The St. Louis Argus. Ad for “Jiven’ in Be Bop.” Page 9. September 3, 1948

- The Washington Herald. Page 47. March 27, 1938

- Washington Afro American. Ad for Sahji at Club Bali. Page 15. December 25, 1948

Articles

- Buffalo Courier Express. “Sahji Featured at the Palace.” Page 29. July 20, 1941

- New Journal and Guide. Page 16. April 15, 1939

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “One of the Younger Pioneers.” Page 20. April 16, 1938

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “New Mimo Club Revue Not Up to Standard.” Major Robinson. Page 20. September 27, 1941

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “More to Correct What’s.” Page 22. October 19, 1946

- Press of Atlantic City. “From Coast to Coast.” Page 11. September 3, 1938

- The Afro American. “Nitery Star Engaged.” Page 13. March 8, 1941

- The Afro American. “There’ll Be No ‘About Face’ When Sahji Gets Going at Uncle’s Camps.” Page 13. January 10, 1942

- The Afro American. “Around the Motor City.” Detroit, MI. Page 19. April 4, 1942

- The Call. Page 17. April 14, 1939

- The Chicago Defender. Page 10. March 25, 1939

- The Chicago Defender. Republic Theater. Page 15. April 8, 1939

- The Chicago Defender. “Madeline Jackson in Detroit Revue.” Page 21. December 9, 1939

- The Morning Call. “Burlesque.” Page 11. April 23, 1938

- The Washington Daily News. “Two Shows in One at the Gayety.” Page 24. March 28, 1938

- The Washington Herald. “Black and White Revue at Gayety.” Page 11. March 28, 1938

- Times Herald. “60 in latest Gayety Show.” Page 20. March 25, 1938

- Detroit Free Press. Photo of Sahji. Page 21. April 22, 1942

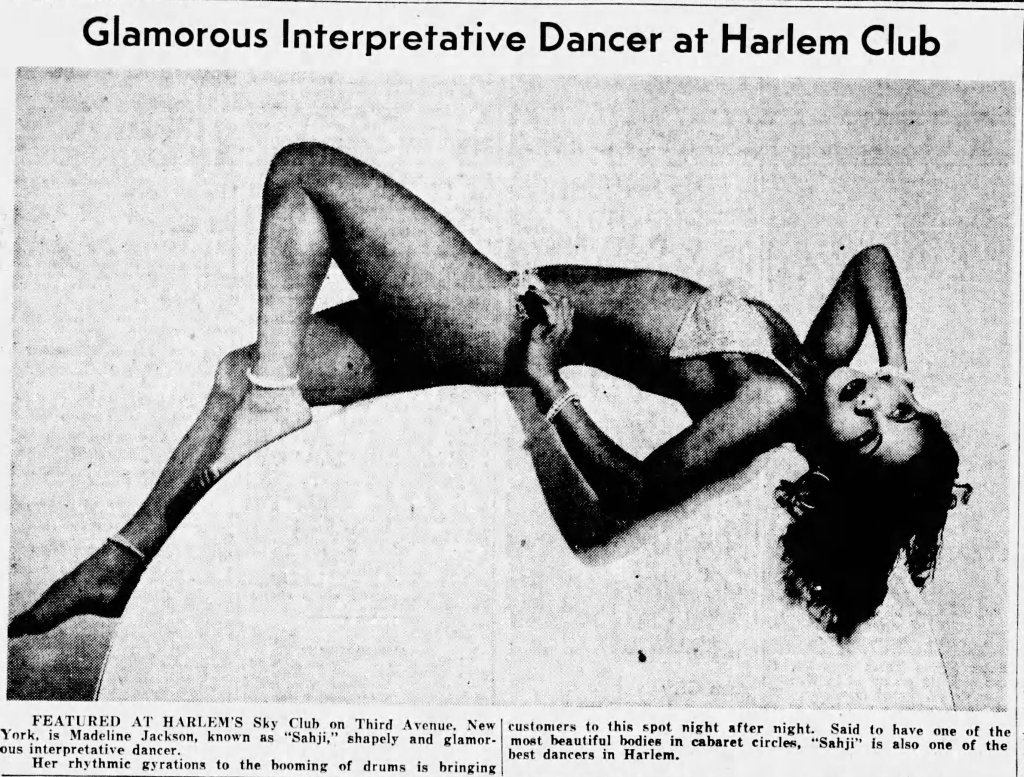

- New Journal and Guide. “Glamorour Interpretative Dancer at Harlem Club.” Page 16. June 17, 1939

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “Exotic Star Becomes Bride.” Page 21. May 24, 1941

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “‘Sahji’ Tied the Knot.” Page 21. May 17, 1941

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “Shot in the Arm to Show Business.” Page 20. March 2, 1946

- New Pittsburgh Courier. “The Girls Have It.” Page 22. July 17, 1948

- Afro American. “Madeline (Sahji) Jackson.” Page 14. February 1, 1941

- Afro American. “She’s Mrs. Now!” Page 13. May 17, 1941

- Afro American. “Going into Private Life.” Page 13. April 11, 1942

- The Chicago Defender. “Back in Harlem.” Page 20. June 17, 1939

- The Chicago Defender. “From Harlem.” Page 62. February 8, 1947

Leave a comment