American burlesque history is usually traced to Lydia Thompson’s “British Blondes” in New York, but the Hyers Sisters were already performing burlesque‑style operettas on the West Coast by the late 1860s. Touring from California and billed in 1879 as “The Only Colored Burlesque Troupe in the World,” Anna and Emma Hyers used satire and musical comedy to tell stories of Black dignity and freedom. Because they were Black women exploring different ideas than Thompson’s all‑white troupe—political uplift instead of sexual spectacle—their contributions were not included in the mainstream burlesque narrative. Yet their work shows that American burlesque had multiple beginnings, and one of them was led by the Hyers Sisters.

In the turbulent years after the Civil War, America’s theaters became contested spaces where race, class, and culture collided. Opera houses were not just sites of entertainment—they were arenas where the nation rehearsed its anxieties about freedom, equality, and belonging. Into this charged atmosphere stepped the Hyers Sisters, Anna and Emma, two young African American performers from Sacramento whose voices carried both artistry and defiance into their adulthood.

Early Life & Education

Anna Madah Hyers (1855–1929) and Emma Louise Hyers (1857–1899) were born in Sacramento, California, to Samuel B. Hyers and Annie E. Cryer. They traveled to California during the Gold Rush. Their father was a barber and amateur opera singer—a profession that gave him both community standing and enough income to invest in his daughters’ futures.

Samuel Hyers arranged for Anna and Emma to study with prominent European instructors and professional opera singers in California. Anna trained as a soprano, while Emma had a contralto voice. Samuel would go on to become his daughters’ manager in their early theatrical careers.

At the time, it was highly unusual for Black girls to receive formal musical education. In the 1860s, most Black children in the U.S. had limited access to schooling, and opportunities for advanced training in the arts were almost nonexistent. The Hyers Sisters’ education reflected both their father’s determination and the relative openness of California compared to the segregated South.

Post-Civil War Context

The Civil War had only recently ended, and Reconstruction was just beginning. Access to education for African Americans was expanding but still contested, especially for women. Black women faced double exclusion—from racial prejudice and from gender norms that discouraged women from pursuing professional careers. Being born in California gave the sisters a slight advantage. The state had fewer entrenched segregation laws than the South, and Sacramento’s growing cultural scene provided opportunities for training and performance. In fact, the Hyers were not listed as “colored” in newspaper articles and advertisements until they traveled outside California on a national tour in late 1867.

Musical Prodigies

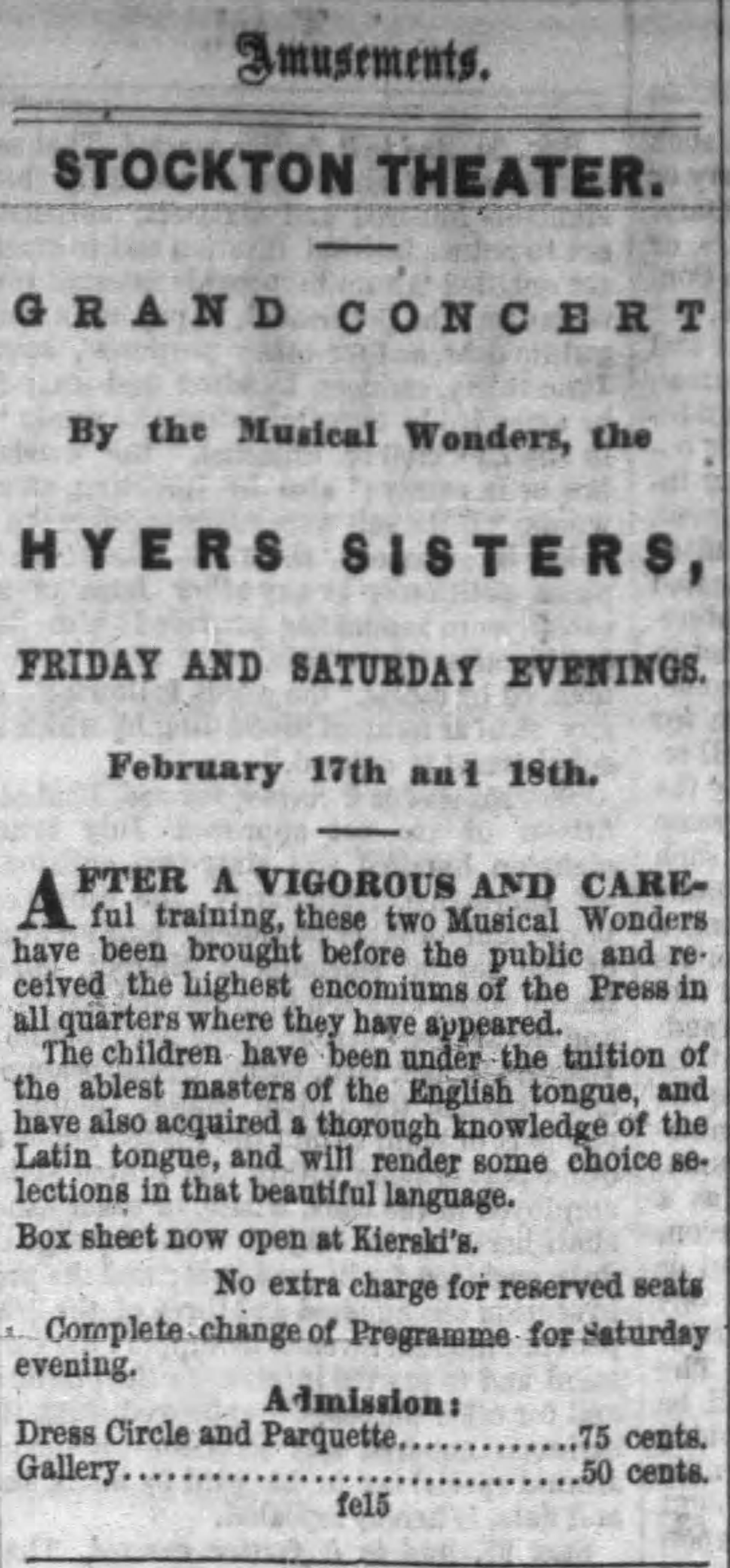

Their first major performance was in 1867 at Sacramento’s Metropolitan Theater, aged just 9 and 11 years, where they stunned audiences with their vocal skills. Their debut was just 2 years after the end of the Civil War. They performed in front of 700 people at the Metropolitan Theater on April 20, 1867. This marked the beginning of their professional theatrical careers. Shortly after they began a national tour which led to their prominent rise in American theater.

By singing Traditional European concert music, the sisters identified themselves as versatile performers, able to go beyond stereotypes of minstrelsy. Yet they were also able to perform in the African American tradition, such as spirituals, which underscored their racial identities.

. . . Each in your voice perfection seem,—

Rare, rich, melodious. We might deem

Some angel wandered from its sphere,

So sweet your notes strike on the ear.

In song or ballad, still we find

Some beauties new to charm the mind.

Trill on, sweet sisters from a golden shore;

Emma and Anna, sing for us once more;

Raise high your voices blending in accord:

So shall your fame be widely spread abroad.

—M.E.H., Boston Daily News (n.d.) [Buckner, Jocelyn. 2012]

Their education allowed them to perform at a professional level equal to white opera singers of the time. This was crucial: it meant they could not be dismissed as “amateurs” or “novelties.” Instead, they were recognized as serious artists by the public, which gave them the credibility to later stage their own productions.

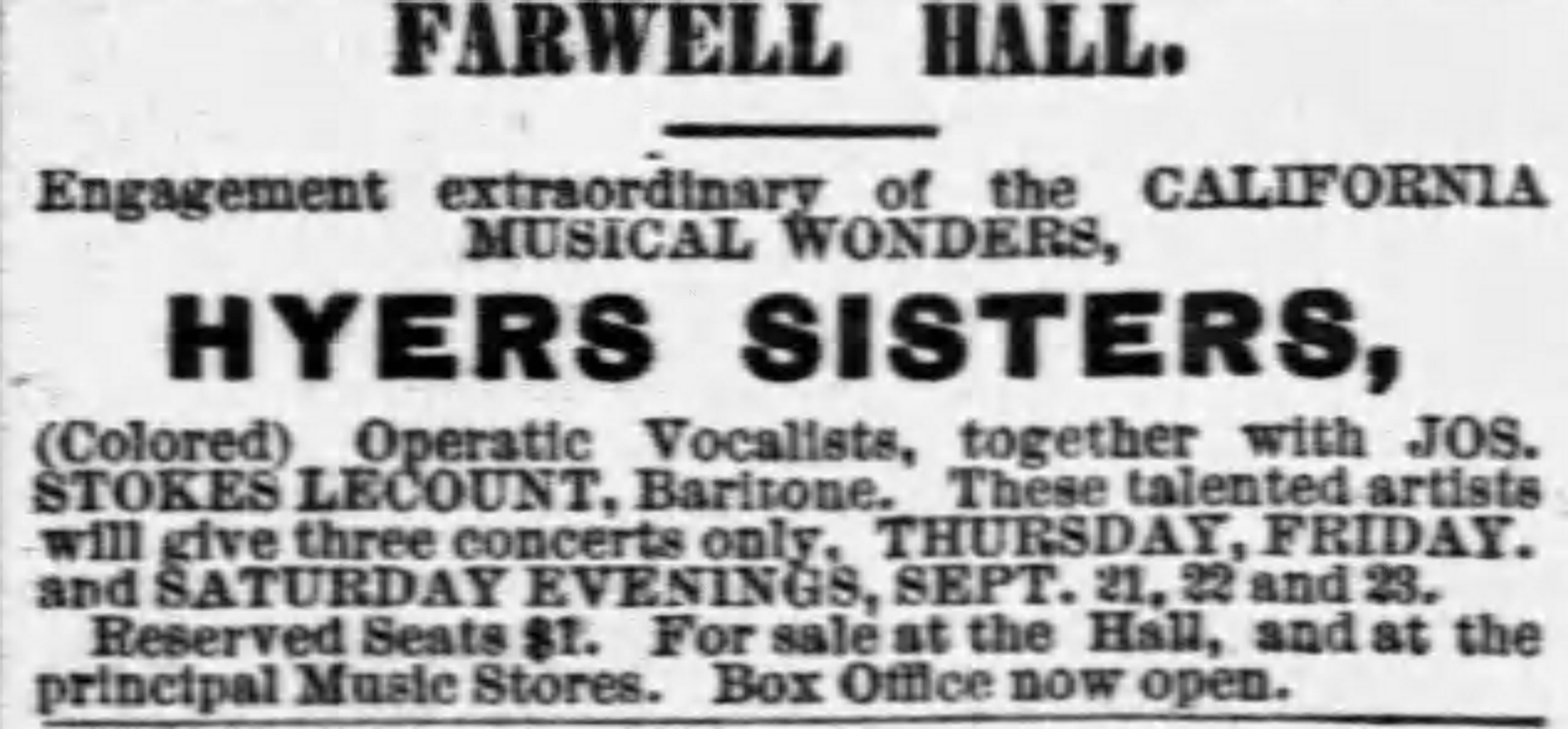

By 1871, they were touring nationally, becoming the first African American women to achieve mainstream success in opera and concert performance.

As Cali Weekly emphasizes, their productions were not just milestones in Black theater but in American musical theater itself. They helped invent the genre by blending music, drama, and social commentary in ways that prefigured Broadway.

Before Lydia Thompson

When Lydia Thompson’s “British Blondes” burst onto the New York stage in 1868, they were credited with introducing burlesque to American audiences through parody, spectacle, and satire. Yet on the opposite coast, Anna and Emma Hyers were already carving out their own path. Debuting in Sacramento’s Metropolitan Theater in 1867, the sisters began touring the West with comic operettas and musical parodies, blending classical training with popular entertainment.

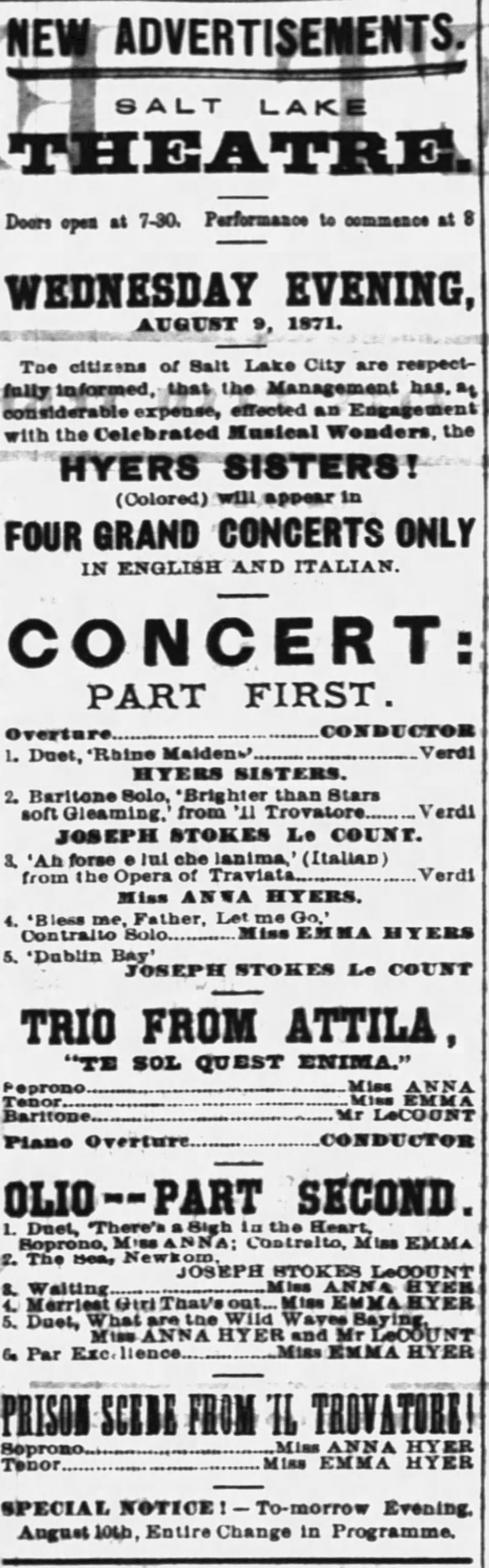

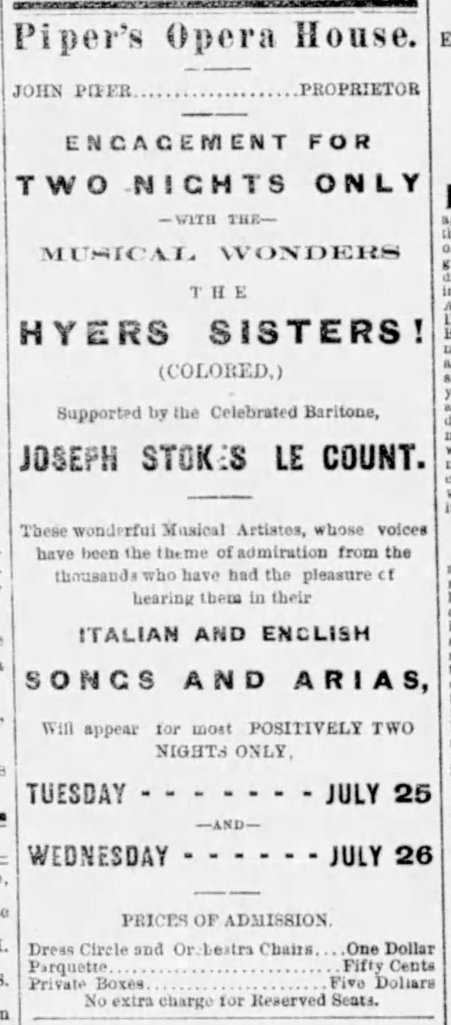

In 1871 they began singing operettas and arias in Italian and English with Josephe Stokes Le Count, a baritone. In Boston, they performed at the 1872 World Peace Jubilee. This production was one of the first racially integrated musical productions in the country. They were well received in Boston.

Producing & Performing Burlesque

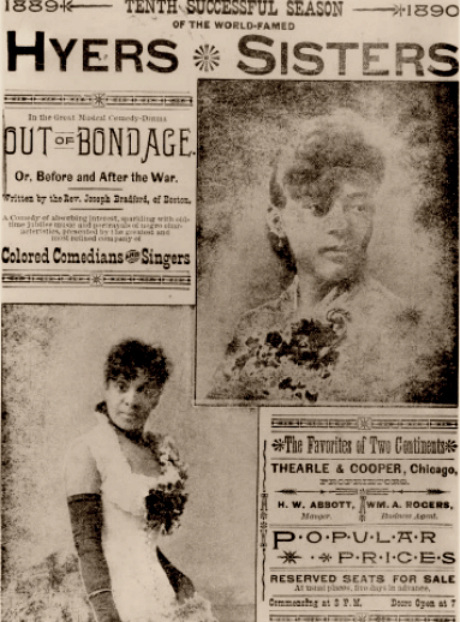

Early 1870s advertisements billed the Hyers Sisters as “The Only Colored Burlesque Troupe in the World.” That phrasing is remarkable: it not only situates Anna and Emma Hyers within early burlesque tradition but also underscores their uniqueness as Black women leading a company in a genre dominated by white troupes.

By the mid-1870s they were producing original works that carried the hallmarks of burlesque: satire, role reversals, and comedic parody. The sisters soon moved beyond concert tours to produce original plays with collaborators like Joseph Bradford and Pauline Hopkins.

Their original shows included:

- Out of Bondage (1876) – a slavery-to-freedom drama, considered the first African American musical play.

- Urlina, the African Princess (1879) – the first known African American play set in Africa. Written by E.S. Getchell.

- Peculiar Sam, or The Underground Railroad (1880) – a burlesque version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin written by Pauline Hopkins, an African American woman from Boston.

- Colored Aristocracy (written 1877, staged 1891) – exploring class tensions within Black communities.

Overall they had at least 6 shows between the 1870s and 1880s. They traveled with their own shows through the 1890s until Emma Louise’s death in 1899. Anna Madah continued to perform in a traveling vaudeville troupe.

Trav S.D. notes that these productions were groundbreaking because they rejected blackface, at a time when minstrelsy dominated American entertainment. Instead, the Hyers Sisters staged dignified, complex Black characters, offering audiences a vision of humanity and resilience. Some scholars argue their productions were among the first true American musicals, not just the first Black musicals.

The Hyers Sisters used burlesque to dramatize emancipation, dignity, and Black humanity. It’s clear they were not imitators but innovators, launching American burlesque from the West Coast in the 1870s and laying the groundwork for later stars like Bert Williams, George Walker, Aida Overton Walker, and the Whitman Sisters.

Out of Bondage | 1876

Out of Bondage was a production in three acts. The first illustrated “the dark days of African bondage” in Kentucky. The second act depicted the Union army and freeing of slaves. The final act presented an African American family in the North, five years after the end of the war. The idea was unique and mixed comedy and music with social commentary.

The Milkwaukee Commercial Times stated, “The Hyers Sisters have the good fortune to combine in their entertainment the very best features of minstrelsy without any of the objectionable features.” – Green Bay Press Gazette. “The Hyers Sisters.” Page 4. October 1, 1877

Peculiar Sam; or The Underground Railroad | 1879

The Hyers Sisters and Sam Lucas collaborated with 20-year-old playwright Pauline Hopkins to produce a new play expanding on the themes explored in Out of Bondage. Peculiar Sam was copyrighted and first produced in the same year as the Kansas Exodus (earliest major migration of African Americans out of the South after the Civil War). Their production provided American audiences with the first staged reenactments of slavery that were not through the lens of white imagination.

This production broadened how African American life was represented on stage in three significant ways: it used dialect with greater subtlety to reflect individual Black experiences rather than relying on stereotypes; it introduced a Black male hero, portrayed by leading performer Sam Lucas; and it staged a believable romance between Black characters, building on the Hyers Sisters’ earlier groundbreaking depictions of African American love.

The play itself was a slavery‑to‑freedom epic, tracing one family’s escape from a Mississippi plantation to Canada, interwoven with jubilee songs, spirituals, and classical concert music. While its storyline echoed Out of Bondage, Hopkins’s four‑act drama focused specifically on journeys along the Underground Railroad. The cast included Sam—described as “a peculiar fellow” and played by Lucas—alongside Jim, a Black overseer; field hands Pete and Pomp; Virginia, Sam’s love interest (Anna Madah Hyers); Juno, Sam’s sister (Emma Louise Hyers); Mammy, his mother; and Caesar, a station master.

Beyond dramatizing the perils of escape, the script offered one of the earliest stage portrayals of romantic love between two Black characters—Sam and Virginia—and marked the first such depiction written by an African American woman and performed by an all‑Black cast. Although William Wells Brown had earlier imagined romance between runaway slaves, Hopkins’s work advanced this tradition with new depth and realism.

Peculiar Sam was among the first plays to dramatize the fear, abuse, and lack of autonomy endured by enslaved African Americans. It highlighted how master–slave relations denied the enslaved any will beyond serving the owner, reducing them to property. On stage, audiences saw Virginia’s suffering and Sam’s defiance—his refusal to let her be forced into marriage with Jim, and his declaration of love and respect for “Jinny,” which drives him to lead his family to freedom.

In the final act, set six years after the Civil War on Christmas Eve, Sam is now a congressman in Ohio and Jim a lawyer in Massachusetts. Jim releases Virginia from their forced union so she can marry Sam, but the return of the old overseer—whose approval is still required—underscores how slavery’s shadow lingers even in freedom. The scene highlights the enduring reach of the “peculiar institution” into the lives of Sam and Virginia.

Unfortunately, the play was not widely held as a success and Lucas even deemed the piece “failed as the time was not propitious for producing such a play.” Audiences were not always open to receiving Hyers’ treatment of recent historical atrocities.

Urlina, the African Princess | 1879

Urlina stands as the earliest documented African American play set in Africa, aligning with the Hyers Sisters’ lifelong commitment to promoting racial pride and uplift. Urlina showcased crossings of gender, race, and cultural identity through casting that echoed early burlesque and English pantomime conventions: a young ingénue, a male lover played by a woman, a comic dame played by a man, and other humorous figures. Using opera bouffe, the Hyers Sisters presented African royalty—an unfamiliar concept to most audiences—within a familiar Western style.

Unlike their earlier works, which resisted stereotypes by reworking minstrel tropes, Urlina advanced a subtler strategy of “disidentification,” presenting new material inside dominant theatrical traditions to promote racial pride and equality without provoking hostility. By depicting dignified Black characters in a recognizable format, the Hyerses staged romance and respectability in ways that challenged prejudice while remaining accessible, entertaining, and socially acceptable.

Emma Louise assumed the role of Prince Zurleska. By assuming male costume, Emma burlesques the role. Jocelyn Buckner references Garber to describe Emma’s performance as a male character as “transvetism” and not seen in the same canon as burlesque.

Garber describes “transvetism”:

“transvestism [as] a trickster strategy for outsmarting white oppression, a declaration of differences . . . The use of elements of transvestism by black performers and artists as a strategy for economic, political, and cultural achievement . . . marks the translation of a mode of oppression and stigmatization into a supple medium for social commentary and aesthetic power.” (Buckner, Jocelyn)

I believe the Sisters were performing burlesque, not just English pantomime with “transvetism.”

The plot of the musical was briefly explained in the Atchison Champion:

“Kyaba Kima Kenia, is a usurping king of some African tribe, who has banished the rightful heir to the throne, the Princess Urlina, from her infancy, to a desert island with no other attendant but her maid Nubiana. Prince Zurleska is the son of the usurper, and is a braze harum scarum young fellow. Buddha Gna is an Obi woman or witch who hates the king for injuries inflicted upon her family years before, and is continually plotting against him with the help of evil spirits. She tells prince Zurleska the story of the captive princess, and shows her to him in a vision; he falls in love with Urlina and vows to rescue her. The plan of the witch is to humiliate the king and place the princess on the throne, and thus satisfy her vengeance. Zurleska finds the princess and takes her from the island, but on entering his father’s kingdom, he and his friend Kokolah, with the princess and her maid, are captured by the king’s soldiers for treason in plotting against their monarch, before whom they are brought, and not withstanding the tears and entreaties of Queen Ludda Kester, they are doomed to slow starvation in prison, with exception of Kokolah, who, disguised as Lord Prosperus, a traveller, greatly tickles the king’s fancy by exhibiting the intelligence and agility of a pet ostrich, for which he is spared, and with the assistance of Uzziji, an Irish missionary, is successful in liberating the prince and princess, when the latter is restored to her rightful possessions, whereby the wicked king is discomfitted.”

-“Hyers Sisters” Page 4. November 27, 1878

About the Hyer Sisters: “Few even among the most experience professional singers are possessed of a more naturally graceful style. They are both young[…]Miss Annie has a purse, sweet, clear and flexible soprano voice, of good compass and power, one of the finest and best cultivated we have yet heard upon that stage, while her sister Emma, who is the youngest, is possessed of a rich, full and powerful contralto voice[…]ranging well into both tenor and bass.”

– The Gold Hill Daily News. Urlina, the African Princess at Piper’s Opera House, Virginia. Page 3. July 26, 1871

The Nebraska Chronicle stated,

“A critical audience attended the Hyers Sisters’ concert last night, and everybody went crazy over it, bursting out in ecstatic rapture and thunders of applause, piling encore upon encore, as if it could never drink enough of that exquisite melody.” (August, 1871)

The Hyer Sisters were performing burlesque by emphasizing gender, race, and parody. Their original productions employed satire, role reversals, and operetta conventions–all hallmarks of burlesque–but with a radical twist: they rejected blackface and staged dignified, complex Black characters and stories. Their work didn’t fit neatly into the white-dominant narrative of burlesque history, which often valorized spectacle and stereotype. In effect, their political use of burlesque made them less visible to later historians who equated burlesque with sexual provocation or racial caricature.

Various Newspaper Advertisements:

The Kansas City Journal described the Hyers’ company performances and noted on Emma and Anna:

“…the contralto voice of Miss Anna in the song ‘Waiting’ delineated the germ of the whole performance. In this, the voice ran by easy gradations down into a whisper, and thence into the whisper of a soft breath that lost nothing in distinctness in regions farthest from the stage… The performance concluded with the prison scene from ‘Il Travatore.’ Here both of the sisters gave superb execution…” – Kansas City Journal. Page 4. “The Hyer Sisters” September 2, 1871

The Wagner Letter | Segregation in Virginia

In the 1870s, segregation was not yet universally mandated by law, but it was enforced socially. Black patrons were relegated to “colored sections” in theaters, trains, and churches. The Wagner letter from Virginia City captures this tension:

Samuel Wagner writes to the owner of the Piper’s Opera House, John Piper, on behalf of the People of Color of Viriginia City.

He offers “sincere thanks” for the owner’s “disinterested kindness in allotting us the Orchestra Chairs during the engagement of the Hyers Sisters at the Opera House. We were under the impression that as ‘Citizens’ we were entitled, upon the payment of the usual admission fee, to select what part of the Opera House (it being a place of public amusement) we would occupy, and would no doubt have been content, in recognizing social as well as political equality with our Republican brethren, to have seated ourselves in the Dress Circle or even the Pit–But to have ‘reserved’ for us exclusively the Orchestra Chairs–“the best seats in the house,” and that gratuitously, is a consideration on your part as unexpected as it is undeserved…”

[Wagner continues]

“It would have indeed been humiliating to us to encounter the unpleasant looks of the “descendants of the old-time Chivalry;’ yet sustained by the pleasure and gratification that we are certain would have remained in the looks of our Republican friends not of the “old-time Chivalry,” we might have passed the ordeal. It would have been very trying to our sensitive natures; and to your foresight we are indebted for not subjecting us to the trial. Again thanking you for your kindness and forethought in our behalf and the just appreciation of the relative position we bear toward the old-time Chivalry, I remain. – Yours, etc., Samuel Wagner”

Wagner says they assumed that as “Citizens,” upon paying admission, they could sit wherever they wanted—whether in the Pit or the Dress Circle. He’s asserting their civic right to choose as citizens, not to be restricted to a “colored section”–stating it would be social and political equality for them to sit with “Republican brethren” in the Pit (closest to the stage usually) or the Dress Circle (usually seats above the stage with a better view.) He notes they “would no doubt have been content” with those areas, meaning they weren’t demanding the best seats, just equal access. At Piper’s Opera House the cost of a Dress Circle or Orchestra seat was $1, compared to 50 cents in the Parquette, or $5 for private boxes.

His gratitude toward Piper for reserving Orchestra seats is also a subtle critique: it acknowledges that equal access was not guaranteed, and that dignity in public life required deliberate intervention. The letter stands as both a record of exclusion and a reminder of how African Americans asserted their right to belong in cultural spaces during Reconstruction.

The Third Hyers Sister

May Hyers was the third sister, perhaps a half-sister, and not as hugely successful as her older sisters. May entered the theater scene in 1883 as a member of the Samuel B. Hyers’s newly formed Colored Musical Comedy Company. From this year onwards, there were two separated troupes–one referred as The Hyers Sisters Combination and the other The S.B. Hyers Colored Musical Comedy Company in which May performed leading roles in. This can be corroborated with newspaper articles and advertisements for both troupes performing different shows at different locations.

Brief Notes on Their Personal Lives

The Sisters’ father, Samuel Hyers, filed for and was granted a divorced from their mother, Annie, in May 1870 on the grounds of ‘adultery.’ The pair had been married in Troy, New York in 1854 and had only 2 children (hence why May Hyers may be a half-sister).

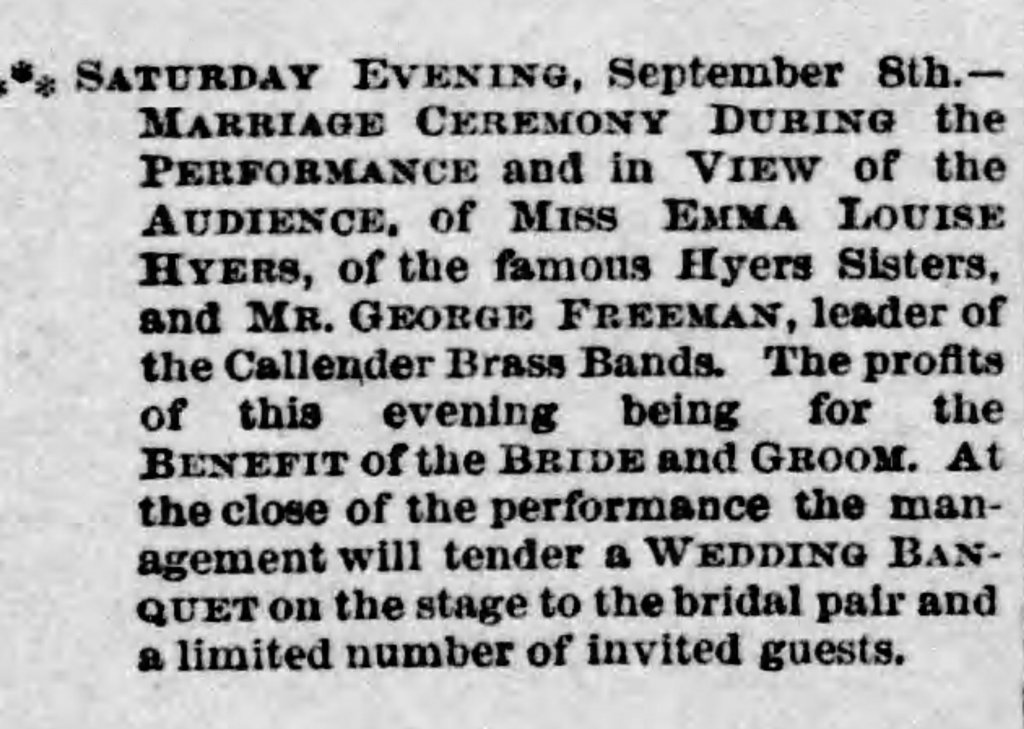

Emma Louise is Married

Emma Louise married George Freeman in 1883 in front of an audience of unsuspecting patrons of the Baldwin Theatre in San Franscisco during a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by the Callender’s Minstrels. The wedding ceremony was held on stage during the show and a banquet was held after on stage for the bride and groom. George was the bandleader of the Callender Brass Bands.

The two remained married until George’s death around 1898–he died of “heart disease in the streets of Pittsfield, Illinois, during a parade of the Primrose and West black and white minstrels.” (The Colored American. “Mary Ann Freeman.” Page 14. December 22, 1900)

Emma Louise died around 1899, the causes unknown.

Anna Madah married Sam Lucas, the comedian, and continued performing burlesque until her passing in 1929. Sam and Anna Lucas performed with Sam T. Jack’s Tenderloin Company, an all-Black burlesque troupe.

The Hyers Sisters’ Legacy Continues…

Their legacy survives today in a new series of films, The Hyers Sisters Dream and Legacy, produced, directed, and written by Susheel Bibbs. Here is the “About” section from the film’s website:

“When night riders and lynching terrorized black people and black-face minstrels ridiculed them across the land, Anna & Emma Hyers, popular late 19th century, African-American touring-opera artists, left opera to stand up for the dignity of their people as “voices for freedom,” changing minds and hearts with works that revolutionized American Music Theater. Yet their story has been unsung.

In her series of 3 short films, which award-winning producer-director Susheel Bibbs has called Voices for Freedom, the first film is on PBS; the next has toured internationally and won 9 awards, and this one, called The Hyers Sisters’ Dream & Legacy– incorporates and surpasses them all. Winner of the American Filmatic Arts Award, the top short-documentary award in Hollywood’s Olympus Film Festival, and international festival screenings in its first year, this film continues to garner laurels.

The Hyers Sisters were the first African-American women to become successful, national touring-opera artists. But in 1876 they left opera and stood up to oppose the touring minstrels’ negative imaging of their people, and for the next 20 years they popularized lovable, musical stories that featured black leading players and integrated casting for the first time. These influenced all music theater that followed, depicted black dignity and life from slavery to freedom, and became known as The First American Musicals!

Metropolitan Opera superstar Denyce Graves hosts; PBS host Akiba Howard narrates, and acclaimed rapper WolfHawkJaguar serves as a poet for our lives today. Starring Shawnette Sulker as Anna Hyers, Hope Briggs as Emma Hyers, Susheel Bibbs as famed historian-reporter Delilah Beasley, Tichina Vaughn as Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield & A Seer, Robert Sims as the Preacher & Ole Uncle Eph, and Omari Tau in cameos as John Luca, Sam, and Prince. Esteemed commentators are Rick Moss, Ph.D, Susan Anderson, Thomas Riis Ph.D, Halifu Osumare Ph.D, and the starring artists.” – thehyersisterssite.com/the-film

The Hyers Sisters as Early Burlesquers

As Cali Weekly and Travalanche both emphasize, the Hyers Sisters helped invent American burlesque and musical theater, and they did so while fighting against the tide of exclusion. Burlesque, opera, and musical drama were stages where America rehearsed its politics, and the Hyers Sisters stood at the center of that stage.

The Hyers Sisters pioneered a West Coast burlesque tradition in the 1870s, parallel to Lydia Thompson’s British importation. Their refusal to reinscribe racial stereotypes—choosing instead to dramatize emancipation, romance, and dignity—meant that later historians overlooked them in burlesque’s origin story. Yet contemporary advertisements and productions make clear that they were recognized as a burlesque troupe, and their subversive approach deserves to be restored to the burlesque history!

Sources

Websites:

- Hyers Sisters – Wikipedia

- The Hyers Sisters Debut On Stage – African American Registry

- How two Sacramento sisters changed musical theater | abc10.com

- The Legacy of the Hyers Sisters: Pioneers in American Musical Theater

- The Beginnings of Burlesque | Loose Women in Tights

- For Black History Month: The Hyers Sisters – (Travalanche)

- https://www.thehyerssisterssite.com/

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/84163163/madah-anna-fletcher

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=227361

- https://face2faceafrica.com/article/hyers-sisters-the-two-unsung-african-american-operatic-prodigies

Books/Publications:

- “”Spectacular Opacities”: The Hyers Sisters’ Performances of Respectability” by Jocelyn Buckner

- Black Performers in Blackface | Who Built America?

- https://lccn.loc.gov/2016658261

- The American Stage by Ron Engle, Tice L. Miller https://books.google.com/books?id=U0LzkKD5_7IC&q=Hyers+Sisters&pg=PA115#v=snippet&q=Hyers%20Sisters&f=false

Newspapers:

- The Appeal. Page 3. August 16, 1902

- The Oakland Times. “Amusements” Page 1. October 15, 1900

- The Topeka Plaindealer. Page 4. August 11, 1899

- Daily Territorial Enterprise. “A Card.” Samuel Wagner. Page 3. August 4, 1871

- Gold Hill Daily News. “Piper’s Opera House.” Page 3. July 26, 1871

- Green Bay Press Gazette. “The Hyers Sisters.” Page 4. October 1, 1877

- Kansas City Journal. Page 4. August 31, 1871

- Kansas City Journal. “The Hyers Sisters.” Page 4. September 2, 1871

- Omaha World Herald. “Edward Freiberger Revisits Omaha; Old-Time Reporter, Comes Ahead of J.K. Hackett.” Page 10. January 31, 1907

- San Antonio Light. “Amanda and Emma Louise Hyer.” Page 4. October 4, 1884

- The Courier. Page 8. October 30, 1878

- The Daily Appeal. “Hyers Sisters.” Page 3. July 29, 1871

- The Daily Nonpareil. “The Hyers Sisters.” Page 4. January 26, 1879

- The Era. Page 10. August 27, 1871

- The Ottawa Free Trader. “Hyers Sisters.” Page 1. October 19, 1878

- The Sacramento Bee. Page 2. February 2, 1871

- The Sacramento Bee. “The Hyers Sisters.” Page 2. February 3, 1871

- The Sacramento Bee. “Wanted a Divorce.” Page 3. April 4, 1870

- San Francisco Chronicle. Page 7. September 2, 1883

- The Colored American. “Mary Ann Freeman.” Page 14. December 22, 1900

- Sun Journal. “50 Years Ago Today.” Page 4. April 1, 1926

Leave a reply to Sam T. Jack: Pioneer of Black Burlesque in America – Iona Fortune Burlesque Cancel reply